Two landmark National Theatre productions were recently rebroadcast to cinemas around the world via NTLive: Frankenstein starring Benedict Cumberbatc and Jonny Lee Miller, and Hamlet starring Rory Kinnear.

The more I learn about West End productions from the last twenty years, the longer the list of productions I wish I’d seen becomes: Ben Whishaw as Hamlet at twenty-three, Tom Hiddleston as a Cassio more compelling than the production’s Iago or Othello, Adrian Lester as Rosalind in As You Like It, and an ever-growing list of Sam Mendes’s landmark productions at the Donmar Warehouse, like Cabaret with Alan Cumming and Company with Lester. It’s always a real treat to find a recording of a production I’ve missed or wasn’t able to travel to London to see, and the National Theatre, now celebrating its fiftieth anniversary, seems to have found the magic recipe for recreating the experience of theatre on film.

The Globe Theatre has been producing DVD recordings of its productions for years, which is great, but my copy of Eve Best’s Much Ado About Nothing has been sitting on my shelf for months even though I’ve wanted to see it for years. The Royal Shakespeare Company also often films its productions, but as was the case with Rupert Goold’s Macbeth and the Hamlet starring David Tennant, they opt to film the production on a film set rather than a stage, creating a weird hybrid of theatre and film that is neither a faithful copy of the play nor quite as polished as a film.

The National Theatre records and broadcasts its productions live to cinemas, on the same night as the performance, and then later in a couple of encore screenings. If you miss it in cinemas, you miss it, which helps make it still feel like an event and forces you to see the production while it’s still fresh, just as Peter Brook would say theatre is meant to be seen. But I only found the screenings for Danny Boyle’s Frankenstein – in which Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller traded parts every night as The Creature and Frankenstein – in my area last year after I’d already missed the rendition with Miller’s Creature. NTLive wasn’t even on my radar when it broadcasted Nicholas Hytner’s Hamlet starring Rory Kinnear, which launched an obsessive Kinnear fandom that I never quite understood. That is, until the National Theatre turned fifty this year and granted the world a second chance to see some of its landmark productions in encore screenings, and I’m now even more impressed with Frankenstein, which last year left me ambivalent, and a diehard Hytner/Kinnear fan.

My first experience with NTLive was Boyle’s Frankenstein, with Cumberbatch as the Creature and Miller as Frankenstein, and I was impressed by how well it translated to the big screen. The camera crew was careful to let us see the show from multiple perspectives throughout the Olivier Theatre where it was performed — from the balcony and the orchestra — but never went in for close-ups that the production wasn’t designed to manage. What I did get was a better view of the actors than most of the audience, but there was still a wonderful sense of space in the theatre, and I could see how the stage was used, the set constructed, and the blocking designed.

Last year, I found Frankenstein interesting but flawed, which I assumed was because of the script and production, especially how flat the scenes between Frankenstein (Miller) and his fiancee (Elizabeth) were. Cumberbatch, who made his name playing intellectual figures like Holmes, gave an impressively physical performance as the Creature: it’s a detailed and methodical performance, in which his Creature’s attempt to learn how to use his limbs mimics how people recovering from strokes or car accidents relearn how to move. Yet it didn’t quite work.

But in the reverse casting, which I saw Monday, Miller’s Creature was wonderfully emotionally resonant, by being more subdued physically, with fewer complicated tics. I found myself tearing up during moments in his performance that left no impression in Cumberbatch’s. Equally, as Frankenstein, Cumberbatch found both intellect and vulnerability, making the character more flawed and sympathetic, a true foil to Miller’s Creature rather than merely a plot device. Where Miller and Harris found melodrama, Cumberbatch and Harris found dramatic tension, and Harris transformed from a grating pest to a feisty woman with a great deal of wit.

Part of the nature of theatre is that every performance is different, so it’s possible the one recorded with Cumberbatch as the Creature was merely an off night; it’s still clear there’s a symbiotic relationship both between creator and created and the actors’ performances as each. The run was sold out even before it began, so seeing it at all was an opportunity only afforded by the advent of NTLive.

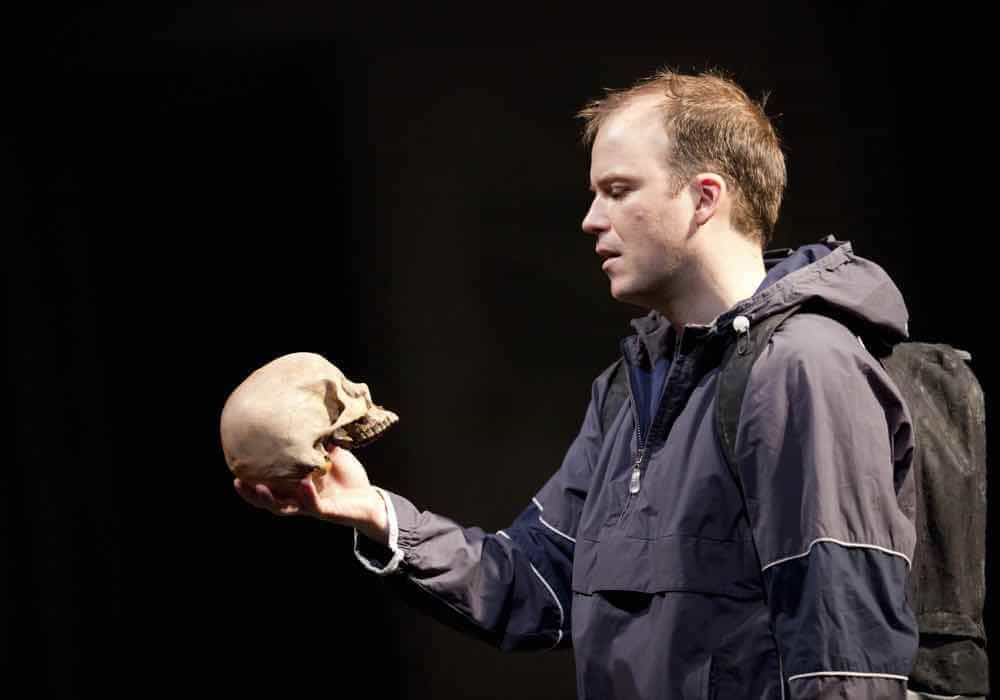

But perhaps even more gratifying was getting to see Nicholas Hytner’s much talked about modern dress Hamlet starring Rory Kinnear from 2010. The trouble with staging Hamlet is that it necessarily requires making decisions about the character, which can mean shades of meaning from the very nuanced text gets suppressed: it’s why almost no production, even one that is often excellent like Branagh’s film, is ever really complete. So what Hytner does is rare: he effortlessly transports the play into modern times to make it easily relatable, and gets such a thoughtful performance out of Kinnear, that this is a near perfect production. Before NTLive, you would have had to be in London in 2010 to see it, but now people around the world have access to an elucidating production that can make clear so much about the play that even the most dedicated Hamlet fans may not have considered, as well as making it completely accessible to neophytes.

This is a highly relatable and accessible production in part because it’s set in a nameless modern dictatorship that follows rules we recognize. Hytner uses this to highlight how much everyone is subject to Claudius’s will — Hamlet can’t return to Wittenberg for school because Claudius won’t stamp his passport — and how the fact that Elsinore is a surveillance state is integral to understanding the performative nature of the characters in the play. We’re constantly aware of the security guards with earpieces who move on and offstage to remind us that no one is ever really alone; everything needs to be interpreted as active performance, including Hamlet’s madness and cruelty towards Ophelia. Because NTLive captured the full performance live, often showing us the whole stage, we observe the scene changes, entrances, and exits, and we become aware that Hamlet is both confined to the stage and Elsinore. He’s miserable, unable to find either solitude or comfort from his friends that have become spies – Polonius, Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern all intrude on Hamlet in his bedroom – which makes it clear how this could drive a thoughtful man into an existential crisis.

By creating an accessible and fully realized world onstage, Hytner allows Kinnear’s performance to fully resonate. And it’s a rare treat to see an actor capture all of Hamlet’s complexity. Kinnear has the perfect combination of irony, comic timing, and emotional turmoil: he can convincingly deliver the mordant one-liners while also showing us a deep loneliness. He has the rare ability to keep up with Hamlet’s intelligence, speaking the lines at the speed of thought, so we get to experience him puzzling things out in real time rather than reciting set speeches. His delivery of Hamlet’s first soliloquy in Act 1 Scene II is a revelation, full of fits and starts, a man interrupting himself as he jumps from thought to thought. Because of NTLive, thousands of people around the world are now privy to Kinnear’s interpretation, which so greatly illuminates the play; the calibre of his performance is so high that few actors anywhere could achieve it. As good as Kinnear is in Bond or as the benign Bolingbroke in Richard II, seeing him as Hamlet is what turned me, like the rest of Britain, into a diehard fan, and it’s great to fully understand why the Independent dubbed him England’s National Treasure.

You can find screenings of NTLive productions at a cinema near you here.