Yossi Aviram’s directorial debut, which he also penned, is a quiet story of two broken men — a father and his estranged son — who are always shot as lonely figures against a vast, beautiful landscape. Aviram began his career as a cinematographer and here, working with Antoine Héberié, who shot the equally gorgeous Jellyfish, he creates a world full of stunning panoramas, from the Bordeaux countryside to the Isreali desert, that his central characters are too detached from to truly appreciate.

When La Dune begins, Hanoch (Lior Ashkenazi) is driving his bike to the stunning dune of the title, in Israel, where he stands in deep contemplation. It’s there that he makes an important life decision, which only proves to his girlfriend that he’s even more screwed up than she had thought. The end of their relationship sends Hanoch to France, where he silently follows around an old man, Reuven (Niel Arestrup), a Paris Police officer in the Missing Person unit who it seems is his biological dad: they both share a passion for chess and bicycles.

Hanoch’s silence and Reuven’s inability to recognize him, even as Hanoch forces himself to cross paths with him, suggests Reuven abandoned Hanoch early on. Aviram subtly hints at what might have happened by showing us Reuven’s life now. He lives with his lover, another man (Guy Marchand), and we can surmise that being gay at the time Hanoch was a child, and from North Africa no less, would not have been an easy situation. Could that be what made him leave? He’s also a reserved man who has never forged any real personal ties to anyone other than his partner and his dog. And Aviram subtly suggests that Reuven’s choice of profession may be far from coincidental.

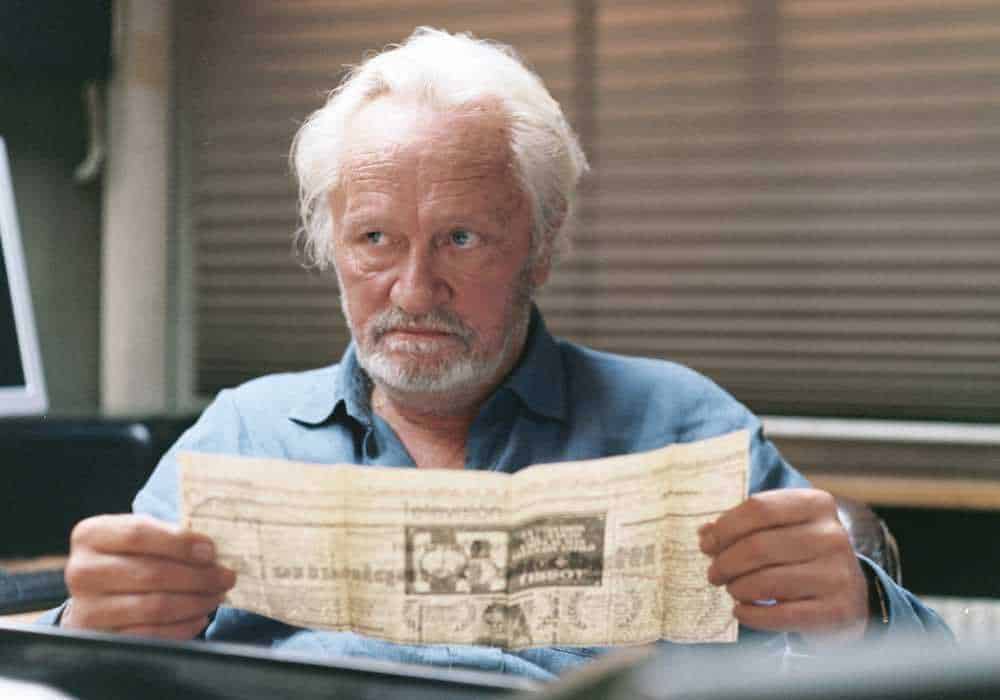

It is, however, useful as a plot device. When Hanoch constructs an elaborate plot to make himself the subject of a Missing Person case, laying the breadcrumbs out for his father to pique his interest, it’s only a matter of time before they’re forced to confront each other. The biggest surprise may be how sympathetic Reuven proves to be, thanks to a sensitive performance from Arestrup, given that he couldn’t even recognize his own son.

Unfortunately, just as the film seems to be getting going, where the possibility for the men to change is imminent, it ends. Aviram excels at suggesting what might have caused both men to become so damaged, but he shies away from exploring it in any detail or depth. The two leads barely exchange more than a few words, which is a shame, because the brief time we do see Hanoch and Reuven together – each played by icons of French and Israeli cinema – is electric. We’re left with a film that has so much potential that it never quite reaches.