Fifty Shades of Grey is far more interested in Anastasia’s thoughts and conscious decisions than in giving Christian even a semblance of a personality.

For a film about a “dreamy” billionaire, Christian Grey (Jamie Dornan), who persuades the virginal Anastasia (Dakota Johnson) to become his submissive in a dom-sub relationship, Fifty Shades of Grey is far more interested in Anastasia’s thoughts and conscious decisions than it is in developing Christian into someone with even a semblance of a personality. At every step of their budding relationship, director Sam Taylor-Johnson (Nowhere Boy) emphasizes Anastasia’s choices, her curiosity, and her control: she may agree to be spanked, but it’s more about her genuine sexual curiosity than bending to her lover’s will. The film’s a hell of a ride, often a fun and thought-provoking one, even though it’s all such camp. But there’s so much talent here — between Johnson, Taylor-Johnson and the excellent but under-used supporting cast of Jennifer Ehle and Marcia Gay Harden — wasted on an often stupid script that’s unintentionally funny as frequently as it is intentionally funny.

The first half of the film is effectively a subversive romantic comedy: he is a fantasy; she is a real person. They meet-cute at the headquarters of his business empire where she’s been sent in her roommate’s stead to conduct an interview for the school newspaper. His formal manner, tailored suits, wealth, and taste for modern design are meant as stand-ins for some kind of sophistication that his vocabulary belies. He finds Anastasia’s clumsy, open, school-girl demeanor — insisting he call her ‘Ana’ when he addresses her as ‘Miss Steele’ — and probing questions disarming. So he makes sure they meet again — being a beautiful billionaire, though, we’re expected to excuse his borderline creepy stalker behaviour. His advances are certainly welcomed. When he just so happens to find himself in the hardware store where she works — he purchases, hilariously, rope and ties — sparks start to fly, with flirtatious banter.

Christian is the king of mixed messages, insisting he doesn’t do romance while constantly making big, romantic gestures — whether it’s sending English-literature major Anastasia a first edition of her favourite book or taking her on an impromptu helicopter ride. He even plays the knight-in-shining armour, rescuing a drunk Ana from a bar, before tending to her vomit and hangover. He spends the other half of their time together pushing her away, telling her he’s bad news, that they can’t be together.

Anastasia is always calling him on it — apparently she never learned that you should listen when people tell you who they are — questioning the rules he insists she play by, and ultimately kickstarting their real romance by drunk-dialing him to scold him for his hot and cold behaviour. His predilection for BDSM means he claims he won’t touch her until she signs a contract, but even when she asks for a business meeting, and we can see her practically vibrating with the desire to have him ravish her, she maintains control and walks out. If he wants to have rules, she’s going to have a few of her own.

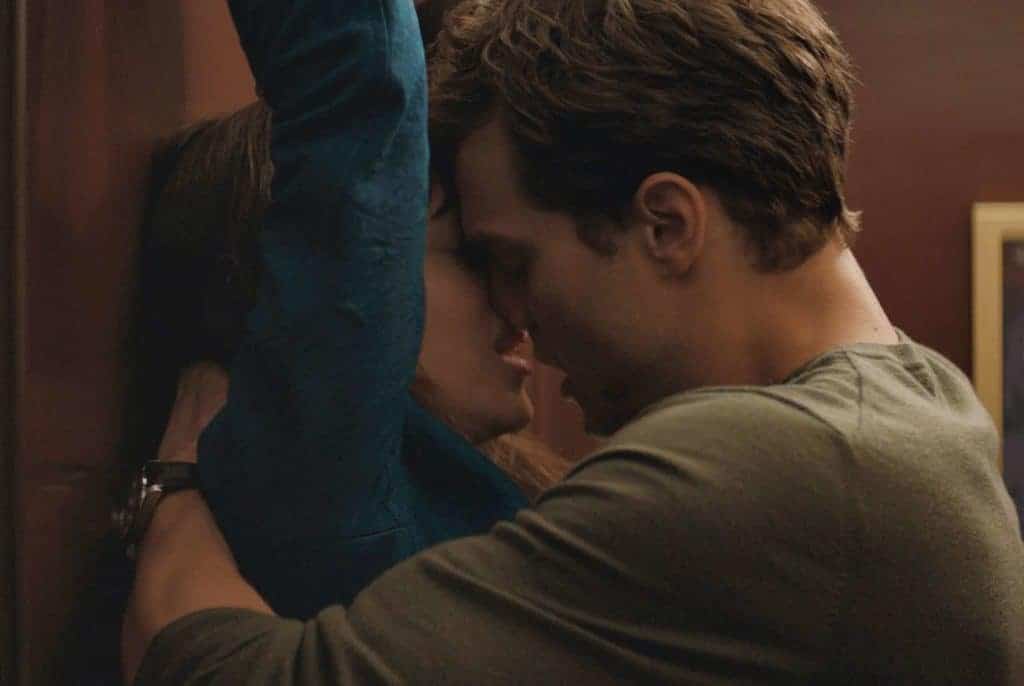

Although it’s only a sort-of sexy film — nothing in it comes close to the eroticism of laundering lingerie in The Duke of Burgundy — and a fairly tame one for BDSM at that — there isn’t even a human toilet! — it’s a very tactile film. When we’re not watching closeups of characters’ faces flushed with emotion or pleasure, we’re usually seeing something being touched up close: a hand grasping a tea-cup, a whip caressing the skin before being cracked, or Christian’s hands sliding up and down Anastasia’s body. Their first sex scene is backlit to emphasize her golden skin and leg hair: every hair is standing up, every graze registering.

The image of Anastasia’s hands being bound during sex — whether with a silk tie or leather cuffs — is not a degrading one: physically unable to participate, to give him pleasure, means everything is about her ecstasy, as she throws her head back and bites her lip. Even when not bound, he won’t let her do so much as caress his back, so deep-rooted are his intimacy issues. Then again, this spares her having to do any work — another part of the fantasy. Although how she can ever fall in love with him, given there’s nothing two-sided about this relationship is a little hard to swallow — no matter how many orgasms he magically gives her without instruction or serious feedback. Their relationship seems to involve little more than frequent sex and expensive dinners: they never actually talk, even as Anastasia begs Christian to open up.

Christian is an outdated stereotype — the stoic, damaged, rich, tall, dark, tortured, and handsome figure — who can only be changed by the love of a good woman. All we get are some burn scars on his chest and a short sob story, about his crack addict birth mom who died when he was four, to explain his kinky proclivities. He is, as Miriam Bale put it, the male manic pixie dream girl. In a day and age when we should be celebrating men who actually express emotion, that crying and sharing is sexy, Christian is practically Don Draper, minus the obvious intelligence or playfulness or complicated emotional issues. Why cast Marcia Gay Harden as his adoptive mother if you’re not going to give her a fighting chance to help give him depth?

Part of Christian’s appeal, of course, is that only Anastasia can break through his bad boy defenses — it’s supposed to be an honour, but in real life, it’s a sign to run the hell away. Yet his stereotypical blandness is a useful role reversal: isn’t this how we’re used to seeing women portrayed, which we accept without batting an eye? But people are likely to get more upset about a two-dimensional, old-fashioned stereotype of a man. Perhaps this will generate a useful dialogue about this double-standard for female and male parts in mainstream movies. It’s still a missed opportunity though: with a woman this interesting, she deserves a man who can keep up with her and challenge her outside the bedroom.

Yet this is never Christian’s film. Don’t be fooled by how frequently Anastasia’s nipples or tuchus are on display, while we never get more than a bit of pubic hair and bare chest from Christian. This is Anastasia’s film: she’s the three-dimensional character we identify with, the one with feelings, who’s genuinely confused. And she’s the reason Christian finds himself confused, breaking half of his silly and delusional rules because he secretly craves intimacy with this woman. But he’s so lacking in self-awareness that he doesn’t understand how he’s self-sabotaging or that he can be intimate without sacrificing his stupid sense of identity — is being emotionally stunted really something worth holding onto?

The countless times that Taylor-Johnson shows Anastasia emerging from or entering into an elevator throughout the film had me frequently thinking back to the season two finale of The Good Wife when the titular Alicia Florrick finally decides to sleep with her boss. But first, she steps onto an elevator in the hotel, on which all the buttons have been pushed. Every time the elevator stops at a new floor, it’s an opportunity for her to leave, to turn back. She has to keep making the decision to go forward with her plan, over and over and over again, and it’s ultimately Alicia who has to open the door to the hotel room they’re headed toward. It’s all about Alicia’s consent and agency.

Similarly, Taylor-Johnson is persistently giving Anastasia an out, a door to walk through that she must deliberately choose to enter or open. Even when she first walks into Christian’s office, she has to open the door herself. As Christian starts to insist more and more that bondage and S&M become part of their bedroom experience — or rather, their sexual exchanges in his all-red “playroom” filled with sexual props — there’s a playfulness to it: he offers her a small taste, checking first that she agrees, and then won’t proceed until she asks for more.

The second half of the film, when the couple start to get serious about their BDSM, is when things fall apart. She keeps pushing him on why a dom-sub relationship is so important to him, and the way she chooses to have him explain it to her is beyond idiotic and absurd. There’s no denying that he’s opened her up to parts of her sexuality she may not have otherwise explored, but if the reason for it is because he — and he actually fucking says this — is “fifty shades of fucked up,” how is that a valuable service? Why must the film insist that she can’t enjoy this in a healthy way?

Christian seems to believe that deflowering Anastasia shouldn’t involve a dom-sub relationship but something gentler and sweeter. They appear to “make love” even though he claims he only “fuck[s]—hard.” If he’s got it in him, and he’s attracted to her because she’s forcing him to feel these things called feelings, why is he so insistent on pushing Anastasia to be his, well, consenting property? His behaviour proves erratic, but we never really get a sense of personal conflict, that maybe he’s being forced to do emotional work he can’t cope with. I guess you have to wait for the sequel if you want to see actual character growth.

And it’s a shame, because what Johnson brings to the part is not just a believable innocence and pluck, but playfulness and emotional maturity. When Christian first ties up her hands with one of his grey silk ties, she giggles at the role-playing: she’s submitting on her terms, aware that she’s still got control even though Christian is such an insufferably emotionally controlling guy.

I suppose part of the point of the story is that Christian is such a cypher, but when they go flying in a glider, much like the one Pierce Brosnan piloted in The Thomas Crown Affair, I couldn’t help but wonder how much more alive and enduring the film could be if Christian had half the wit of Brosnan’s Thomas Crown. Even Taylor-Johnson’s direction is playful: consider that all the secretaries in Christian’s office dress in grey shirts, and even emails and text messages get sent on a grey background. How much better could the film be if there was this kind of humanity on display more frequently in their relationship from both characters? After all, it really does take two to tango. And one of them can’t be holding the camera.