Results, Andrew Bujalski has reinvented and rejuvenated the romantic comedy, dispensing with the formulaic boy meets girl, boys loses girl, boy gets girl back trajectory. Beginning in the middle of the love story, the opening credits play over a moving, striped sheet that fills the screen while moans can be heard in the background. Bujalski skips past the meet cute and falling in love to focus on the more interesting stuff: how can two angry, somewhat broken people, come to terms with their feelings for each other and actually express them, especially when they can barely admit them to themselves? The film seemingly meanders about, immersing us in the world of ferociously upbeat personal trainers and their sometimes reluctant clients, but it’s very carefully, if subtly, structured to push our two lovers together by the end.

They are Kat (Cobie Smulders), a twenty-nine-year-old personal trainer, and her boss, Trevor (Guy Pearce). Trevor owns the gym where they work, where he espouses a mind-body philosophy that he’s fully bought into but that Kat finds to be a bit hogwash. They started sleeping together when she was first hired, but because they acknowledged it was so unprofessional, it never evolved into something more meaningful. Instead, they remain in a romantic limbo. They share the intimacy of lovers — Kat will offhandedly text Trevor that she’s taking a sick day, and he’ll rush over with soup — but pretend as though they’re maintaining their distance.

Every time one of them gives an inch, the other recoils, sending messages that are the opposite of what they really intend. Although these commitment-phobes share a thing or two with the lovers in Will Gluck’s Friends With Benefits, the gender politics and feminism are even more modern in Results. Kat and Trevor’s relationship is a constant give-and-take, whereas Friends with Benefits is that age-old story of a woman who wants more and a man who can’t quite deal. They each take turns pursuing the other but always in a way that allows them plausible deniability: wearing their hearts on their sleeves is a totally foreign concept even though it’s because they’re vulnerable that they’re doing this dance.

When newly rich schlub Danny (Kevin Corrigan), who has just moved to town, walks into the gym in search of a trainer, he becomes Kat’s client and friend in the first act, Trevor’s business partner and confidant in the second act, before helping them find their way back to each other, almost out of exasperation. He’s essentially taking the part of the best friend to whom they can bare their secrets, except that both Kat and Trevor would much rather be talking to each other.

Danny’s a convenient distraction, a pathetic, lonely new-guy-in-town who needs the company. The first time I saw the film, I was frustrated by the amount of time we spent with Danny, who also serves as a comedic foil for our romantic pair because his lifestyle is so different. He eats pizza, smokes pot, drinks with abandon, and completely lacks discipline of any kind. I wanted to get back to our main couple. But his role isn’t incidental. He’s not just filling time. He’s essential for Trevor and for Kat to deal with their issues. He’s a sounding board, a cautionary tale, and he’s the much needed catalyst to let them get past their own bullshit.

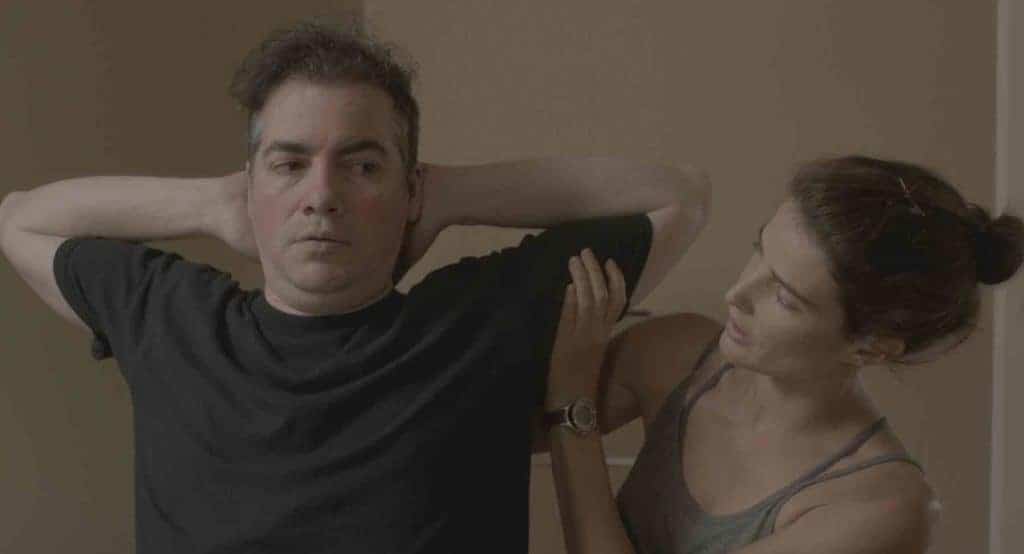

Kat’s and Trevor’s profession is crucial to the build-up of romantic tension. As personal trainers, they’re used to living a disciplined, regimented life, channeling all their anger and aggression into maintaining their fitness level rather than into developing personal relationships. Meanwhile, their relationships with their clients are necessarily intimate, which means they’ve cultivated a great knack for putting up boundaries: watch how Kat keeps her distance from Danny at first approach, asks permission to touch him in order to correct his form, and is generally straight-backed and standoffish as they discuss his body. Building walls between themselves and their clients may be important professionally, but it also means that Kat and Trevor don’t quite know how to tear them down in their personal lives.

Bujalski, who started out in micro-budget mumblecore films, has an exquisite command of spatial relationships between characters both for comedic and emotional effect. The first time Kat goes to Danny’s home to train him, they discuss their regimen in his living room, each sitting on opposite couches 10 metres apart, in a giant, echoing room. Bujalski shoots them in a wide shot, emphasizing the sheer awkwardness caused by the gulf between them. The spaces each of the characters inhabit, from Danny’s empty, unfurnished house, to Trevor’s house that he only shares with his dog are also great for evoking the characters’ loneliness without being too much of a downer. By shooting each character alone and from a distance in their homes, we feel what’s missing but goes unspoken.

Bujalski is terrific, especially, at using the space between characters created by healthy lifestyle objects, for comedic effect. When Kat and Danny drink and watch TV together, Bujalski has Kat sitting on an exercise ball — ever conscious of what’s best for a fit body — which she casually rolls over to Danny’s chair in a two-shot from behind, once she decides to kiss him. This little maneuver unfolds as a terrific piece of physical comedy. At the gym, Bujalski puts a standing desk in Trevor’s office so that when clients like Danny come in to talk, they’re left sitting awkwardly on a low chair while Trevor towers over them — another great sight gag.

The dialogue is great, too. Kat and Trevor bicker with speed and wit, always hiding behind their words. Some of the film’s biggest laughs come from the contrast between the politeness of Trevor’s words and the anger they’re clearly masking. He’s constantly spouting positive thinking nonsense, as much to persuade himself of its value as his clients. Similarly, Kat’s quick temper and over-investment in her clients — she practically bursts on learning a client is quitting — is disarmingly charming. It’s not that the film is hugely quotable, but that words are used precisely and piercingly. Bujalski has a keen sense of irony, which serves the comedy well.

A romantic comedy is nothing without its leads, and Smulder and Pearce make a wonderful, charming pair. Put them in a two-shot together, and it simply crackles. Smulders can do so much with a reaction shot; there’s a particularly good one when Trevor finally confesses his feelings. She’s also got terrific comedic timing, both for banter and physical comedy, and she’s so believably tough and strong-minded that the significant age difference between the pair never really rankled. Although the film never really explains what’s driving Kat’s anger, while hinting more clearly at what’s behind Trevor’s, Smulder sells it so well that you actually have to think about it to find the holes. Pearce is perfect at hinting at the vulnerabilities and insecurities driving Trevor while putting up a front of self-confidence and positivity. Their chemistry would be enough to sell the film, but Bujalski populates their world with nuanced supporting characters and delves deeper into their issues while keeping things fun, fast, and bright.