Hubert Sauper discusses making his film We Come as Friends, creative nonfiction cinema, and the geography of colonialism. This is an excerpt from the ebook In Their Own Words: Documentary Masters Vol. 1. To read the full interview, purchase a copy of the ebook here.

About a year before the 2010 South Sudanese general election, documentary filmmaker Hubert Sauper boarded a lightweight plane that he’d built in France himself and headed to rural South Sudan to make a movie. He was interested in investigating what traces of colonialism still existed in Africa and what its present-day effects are.

As we watch Sauper swoop in on his plane at the beginning of his new documentary, We Come as Friends, he likens himself to an alien from outer space, visiting a foreign land to try to understand it. He films through the window of his plane, a bird’s eye view that acknowledges no borders, as Sauper notes in his voice-over that artificially imposed borders by European colonialists have spawned war across the continent. The nature of his chosen mode of transportation makes him both like other white people, landing uninvited on foreign land, and different from them, because he comes in open-minded, willing to engage.

He spends the first half of the film talking to local Sudanese people, asking them about their views on colonialism and its lasting effects, and to the foreigners who have settled there. He talks to U.N. employees and to Chinese immigrant workers who have come to dig for oil, the valuable resource that’s divided North and South Sudan and caused violent conflict. It’s quickly apparent that these are two groups that never communicate with each other.

The U.N. worker he speaks to talks about locals in theory, but in the film, we never see him actually engage with these locals, because it’s not part of his everyday routine. Equally, the Chinese immigrants work behind a fence that literally divides them from the landscape. It’s just not in the foreigners’ culture to go engage with the locals nor in the locals’ culture to seek out the foreigners. Sauper noted, “My general feeling is that there’s very little connection. And yet there is a huge connection in terms of impact, because the lives of the tribesmen are literally uprooted and digged up, and [the impacts] are deadly sometimes.”

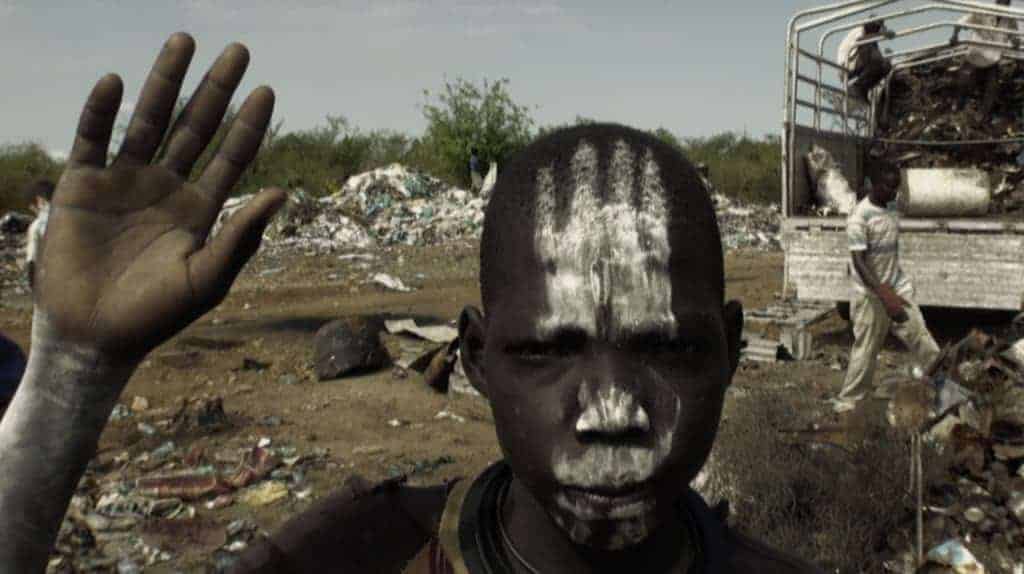

The lack of communication between the two groups is something Hubert Sauper expertly expresses visually. Foreigners are often shot inside rooms or vehicles, where Sauper emphasizes the walls to who how cut off the foreigners are from the locals. While visiting the U.N. building, Sauper trains his camera on a window, looking out onto the landscape, making us ever aware of the boundary that separates them. He also shoots local Sudanese people by their homes at the side of the road, watching foreigners drive by. Sauper asks the locals to tell their stories, and we see just how greatly impacted they are by what the foreigners are doing — not necessarily for the better. Later, we see American missionaries who have settled in South Sudan. While they do actually spend time with the locals, it’s a one-way exchange: The Americans are only interested in imparting their culture and their wisdom, not in hearing the locals speak or trying to understand their situation.

The effects of colonialism can be seen visually through the geography of the places where the locals gather compared with those the foreigners have built. Sauper described how he was using this stark juxtaposition: “I was trying to film history through geography from space by looking at a village that looks like a bee hive — which is very organic and beautiful, in my aesthetic — versus the U.N. camp where everything is straight and structured and lit up and square. I didn’t say that, but I can put it close enough in the film that as a spectator, you can feel that or even see it and analyze it. A lot of people would just have an uneasy feeling seeing this U.N. camp without necessarily knowing why. But one of the reasons why is that a minute before you saw a tribal village. So the clash of cultures and the clash of times can be seen by air.”

To read the rest of the interview with Hubert Sauper on We Come As Friends, purchase a copy of the ebook In Their Own Words: Documentary Masters Vol. 1 here.

[wcm_restrict]

Near the beginning of the film, Sauper laments that the perpetual conflicts in Sudan have forced the natives to learn to march in step and to be soldiers. This kind of organized, regimented behaviour is not natural to them. Similarly, in one scene in the film, we see ten trees in two rows. When Sauper asked the locals about these strangely regimented ordered trees, they told him that some missionary had set up camp there and planted them before fleeing from the conflict.

Sauper explained, “Suddenly, there’s ten trees just standing there, and they say, ‘Yeah, this white guy planted them.’ None of these guys — why would they even plant trees? They would just wait until they grow. And if they were to plant them, they would just plant them near their house. There would be some random, natural order. We [Westerners] are obsessed [with] mathematical order and symmetry.”

Too often nowadays, documentaries have become synonymous with “information dumps,” and the best documentary filmmakers are growing weary of the title. Among them is Hubert Sauper. Although he is insistent that his films are works of non-fiction, he’s described them as non-fiction poetry — something that his colleague and friend Joshua Oppenheimer could likely get behind after calling his two recent films “non-fiction works of magic realism.” As Sauper posited, “There are many ways of telling stories. There are many ways of telling old stories in a new way. This new way is kind of what we as creative people need to find. In this case, We Come As Friends is the old story of domination, colonisation, enslavement, dispossession of cultures and identities, and imposition of a set of values into someone else’s life, [and also] rape, and land theft.”

Sauper elaborated, “But the films are documentaries. The very simple reason is that it is based on fact, and I’m more aware than maybe some other people that fact is a very important element in the films, which does not exclude that I can take something that is factual and push the form, and the creative — what is called documentaire de création is the creative representation of reality. I can take a picture of you. It can look very banal or it can look creative. I can try to move a little bit to this side so I have another background or I can move a bit to this side so something is moving in the background. It changes the equation. But still, you are you, and it’s a real person and a real situation. I’m not asking you to play a Chinese book keeper.”

In the closing scene of the film, Sauper talks to a village elder — someone that Sauper had tracked down through the Oakland Institute — who had unknowingly signed a contract, now available to view publicly online, that sold off his land to Americans. Sauper noted, “It’s an old story. It’s terribly unjust and devastating, but it’s only devastating at the moment you can communicate it as something devastating.” He decided to shoot the scene when it was late at night and a storm was brewing. Sauper recalled, “I knew it might just not work. The light might be too low. Maybe the sound is not good enough. But I gave it a try. I was in the mood to really engage with this man and really try to understand how it happened. I saw his face, puzzled, and I saw that he was kind of outsmarted, overwhelmed, and victimized himself — double-victimized because the people of his village said, ‘Because of you, we don’t own our land anymore.’ ”

“The difference between the factual truth, which is a part of the scene, and the creation of a cinema film, is sometimes like day and night,” noted Sauper, and in this case, “The situation, the mood, the thunderstorm, and the lack of light became the creation of a scene. But again, the contract is the contract, and the signature is the signature. And the man is really the man who had signed it.” Although Sauper chose the moment to shoot this scene spontaneously, his ability to do so required a great deal of planning. Sauper revealed, “I was researching, looking for the guy, looking for a way to find him. It took me a week or two, going there with a team, trying to be there in a secure environment.”

Although this one encounter required careful planning, some of the best moments in the film occurred more organically. “You don’t just meet these kinds of people out of the blue,” remarked Sauper. “You meet them because you condition your thinking. You’re thinking in a certain frequency. You have your antennae out for certain kinds of people and situations and words and images.” Near the beginning of the film, a local Sudanese man trains Sauper’s camera on him, to confront Sauper about “the history of the white man in Africa.” The local man happened to be standing around and piqued Sauper’s interest, so Sauper walked up to him to ask to film him. Sauper recalled, “ ‘Give me your camera,’ he says [to me]. So I see that we have a connection, my new friend within ten seconds. So I hand him over my camera. He turns it around and he starts filming me. The camera is running. He goes, like ‘What are you doing here?’ I said, ‘Well, I come as a friend.’ ”

Occasionally, his subjects found him. Célestine, a Sudanese woman who had run away from the military to the U.S., where she now lives, was one such case. One afternoon, Sauper was sitting in a cafe in Juba, “exhausted and and she walked up to him to ask him about the film she’d heard he was shooting.” Célestine walked up to him to ask if he was “OK” and they started chatting. He recounted, “She’s the mother of seven. She lives now in Nashville,Tennessee. So she tells me that, and I get more interested in what she’s doing back here. We talk, and we talk, and suddenly, my senses waken. I see how eloquent she is and how intelligent.”

Célestine invited Sauper to visit her home and her family, and that’s when something magical happened. She told him about a song that she sang as a student about her country and the loss of her land. When he asked her what kind of song it was, he hadn’t expected her to start singing it, in an emotionally charged moment, but she did. He remembered thinking “ ‘This is amazing.’ I’m catching this moment as it happens. I had no idea she had a song. I had no idea she was going to sing. It’s like the most pure form of cinéma verité. Nothing is more verité than the moment that you discover as you record it. It’s the purest form of non-fiction cinema. But I can only meet her because I was full and loaded of years of thinking around these stories, and there’s one story that unfolds on my camera.”

[/wcm_restrict]