Ninth Floor director Mina Shum: In Canada, “We’re racist but we like to apologize about our racism.” Shum discusses Canadian racism and her new documentary.

Read our review of the film here. The film was also selected as part of Canada’s Top Ten of 2015.

In Canada, “We’re racist, but we like to apologize about our racism,” Ninth Floor director Mina Shum told me. But not talking about it is what makes the Canadian brand of racism so pernicious and so hard to combat. Shum continued, “We grew up with mandated multiculturalism. I really am a child of that. I’m a Chinese Canadian immigrant from Hong Kong. Even though the kids were calling me all sorts of names on the playground, as soon as I walked into a classroom it was like, you know, ‘We’re a mosaic! We’re all inclusive!’ …We’re identifying the problem, but we don’t like to also look at ourselves. How does that trickle down to me on the bus? How does that trickle down to the way my mother is treated because she doesn’t have language?”

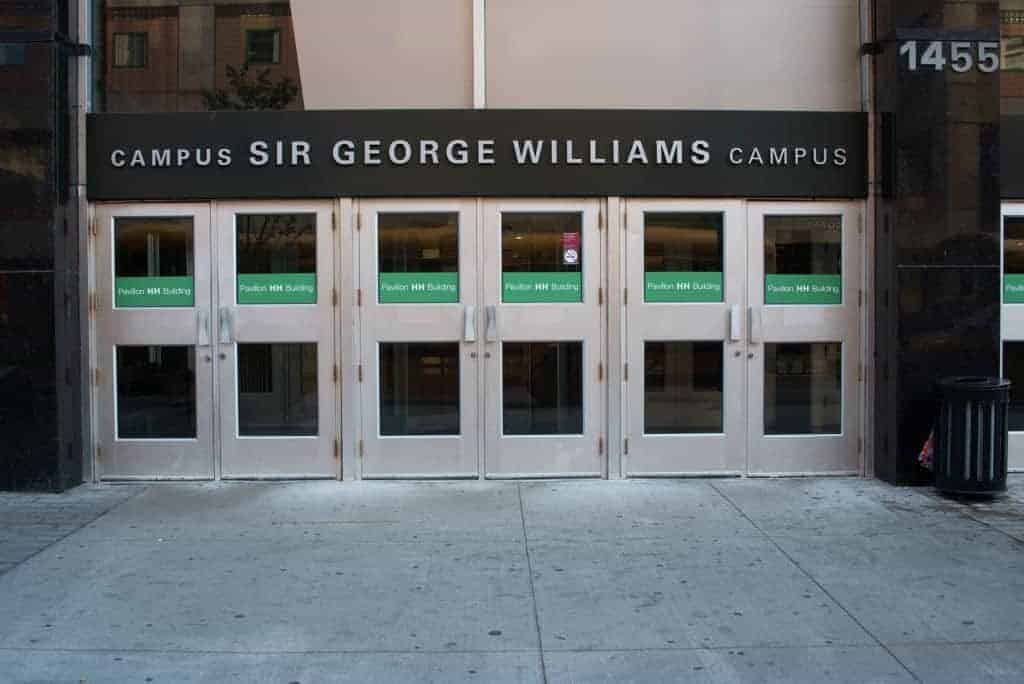

By focusing her film on the crucial but under-discussed Ninth Floor protest against racial discrimination, Shum aims to shine a light on race relations not just in the past but today. In February 1969, students at Montreal’s Sir George Williams University (now Concordia) held a peaceful protest against racial discrimination at the university on the ninth floor of the school. The protest was in response to the university’s inaction regarding a complaint against biology professor Perry Anderson of racial discrimination 10 months before. “If you’re talking about peaceful,” Shum noted, “when the original charges were laid, there was no protest at that point. There was just sort of a trust that due process would occur. When that didn’t happen, they upped it by having a peaceful protest — very Canadian. We will try to make peace before we make war,” said Shum.

The protest lasted two weeks, ending violently when the riot police, who had never been called in to Montreal to deal with a protest, arrived. The students were arrested, beaten, and some were even ultimately deported. “When you’re in denial,” Shum explained, “the violence is how it manifests in the end. I wonder what would have happened if they’d said, ‘You know, you’re right. Let’s have a look at our system and see how there’s institutional racism.’ It would have been a very different story. But denial is one of the worst things you can possibly do, personally and as a society. I think Canada, we’re really aware of that. I don’t know that we’ve solved that problem, but we’re really aware of it.”

Unlike the Civil Rights protests in the United States, Shum noted, “The peaceful protest wasn’t there to provoke brutality. Brutality happened. From a psychological point of view when you’re scared, and that fear reverberates back and forth, often our only recourse is aggression. And I’m like, ‘Is that really our only recourse? Is that the only possible solution to this?’ It’s very primal, really. It’s fight or flight, often. And this is a perfect case of throwing that lens on this situation. It was ‘who’s afraid of who[m] first?’ ”