Director Gillian Armstrong discusses Australian costume designer Orry-Kelly and her gorgeous documentary about his life and craft — with a side of Cary Grant and Betty Davis.

Australian costume designer Orry-Kelly could transform actresses’ bodies, even notoriously ‘difficult’ figures, with his clothes. Bette Davis’s large, droopy breasts posed a particular challenge, since she refused to wear underwire bras — believing they caused cancer. Though Orry-Kelly won three Oscars and designed for countless classic films, including Jezebel, Casablanca, Gypsy, and An American in Paris, he had remained a virtual unknown outside the circles of professionals in his field. Gillian Armstrong’s highly entertaining documentary Women He’s Undressed, which had its international premiere at TIFF, brings Orry-Kelly’s story to the masses, while also illuminating the art and magic of costume design.

Armstrong and her editors had to watch endless footage of Bette Davis to find the right clips to illustrate Orry-Kelly’s genius. She asked her assistant editor, “Can you go through all of Bette Davis’s films from the early ‘30s and try to find some shots where her breasts are moving around under her clothes? Can you find some shots of Bette in the later films where there might be like a pocket handkerchief or something used for distraction above her breast?” Armstrong noted that after screening the film for audiences, “A lot of people have said that after that [part of the film], any time [Davis] came on the screen, all they could do was look at her breasts.”

[quote type=center]A lot of people have said that after that [part of the film], any time [Davis] came on the screen, all they could do was look at her breasts.[/quote]

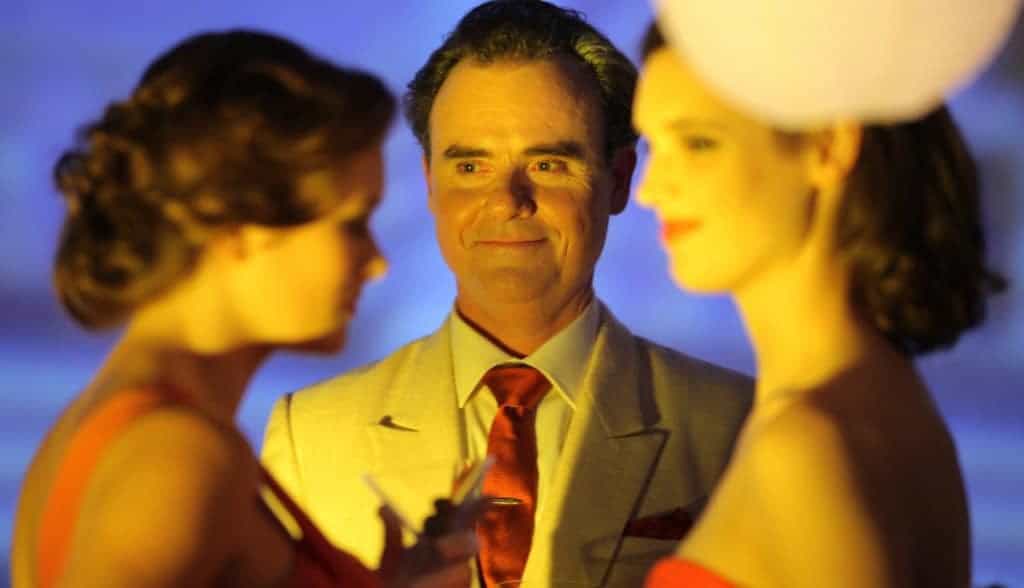

Women He’s Undressed gives us a glimpse of the many other actresses and actors whom Orry-Kelly transformed. He gave the petite and matchstick-like Natalie Wood height and curves by “putting the beading on the side” in Gypsy. He designed Marilyn Monroe’s barely-there dresses in Some Like It Hot, which mysteriously got past the censors. After much campaigning by Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon, he designed their dresses for the film, too: he made them look like rather homely women instead of men in drag. He even taught a young Cary Grant how to wear his signature suits.

Orry-Kelly’s costume design was so influential that it continues to reverberate in films today. When Armstrong interviewed costume designer Colleen Atwood about Orry-Kelly’s work in Irma La Douce, Armstrong recalls, “[Atwood] suddenly realized, ‘You know what? I completely forgot that Shirley MacLaine had this dress with the zips. I think I subliminally got my whole inspiration for Edward Scissorhands from Irma La Douce — and the colour scheme, ‘because I had like black with pastels and everything’”.

Producer Damian Parer initially stumbled upon Orry-Kelly’s story by chance. Armstrong recalls that Parer had “an interest in Australians who’d won Oscars. He was googling and saw this list, and he saw, at that time, Orry-Kelly with three Oscars was the most awarded Australian of all time, and he thought, ‘Who is this guy? I’ve never heard of him.’ So he got obsessed and read about all the amazing films — because no one in Australia remembered him anymore.”