Redford has crafted a densely packed film intended to educate the public about Adverse Childhood Effects, or the very real existence of Toxic Stress.

How do you evaluate a film about a scientific topic? If you’re a film critic by trade, you tend to look for artistic merit. A great documentary should be more than just an info-dump: it should be innovative with form and storytelling. But is that the standard against which to judge every film? Isn’t there value in straightforward educational films whose aim is to communicate information?

As a Ph.D. Candidate with a stake in public scientific literacy, the latter criterion is just as important to me. Can the film affect scientific literacy? Is it giving the already under-informed public bad information? Can it change the way people think? Is it presented in a way to make this accessible? These criteria are equally important to me, and in some cases, I think meeting them is enough to make a doc worthwhile. James Redford’s new film Resilience, another film on the unofficial shortlist for Sundance’s Alfred P. Sloan Prize for Science, is one such movie.

With a runtime of just sixty minutes, Redford has crafted a densely packed film intended to educate the public about Adverse Childhood Experiences, or the very real existence of Toxic Stress, a neurotoxin. Essentially, researchers have discovered that children who undergo trauma — from parental divorce to physical or sexual abuse — experience physical as well as psychological effects. Children hold that stress in their bodies, and it can cause long term health problems ranging from obesity to heart disease to significantly shortened life expectancy. And a shockingly high number of people test positive for toxic stress. As many experts in the film note, this is the biggest public health crisis that nobody knows about.

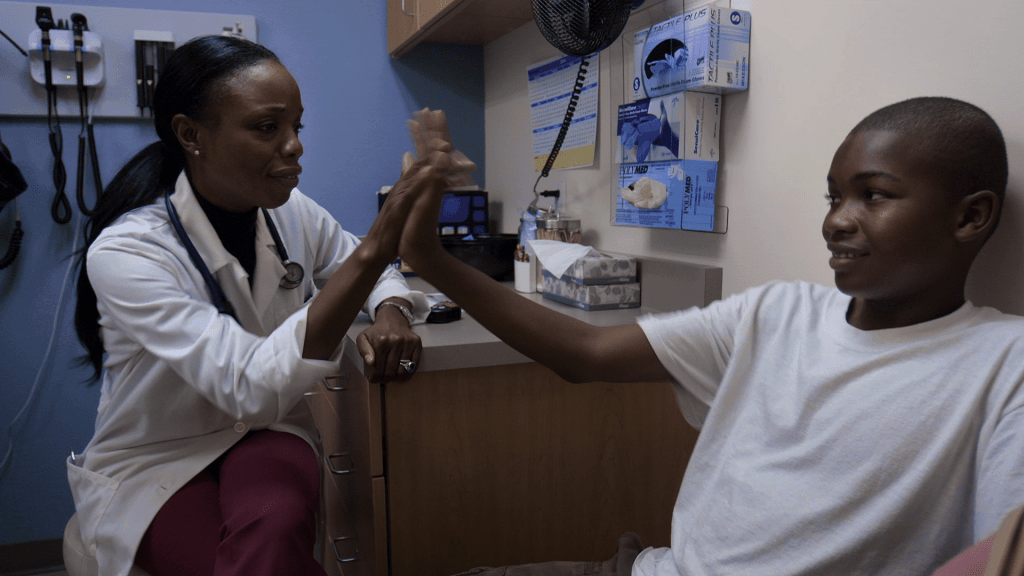

Redford seamlessly cuts together interviews with experts and visualizations in order to effectively explain the science. The sheer depth of information Redford packs into this documentary is itself a feat. To drive it home, he forges an emotional connection to the players involved. We meet children coping with toxic stress and adults who are just not being diagnosed with it. We see how devastating the effects of toxic stress are, both to the patients who suffer from it and to the doctors who treat them.

Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician in a poor neighbourhood of San Francisco plagued by gun violence, is one of Redford’s best subjects. She clearly explains the science and what she sees on a day-to-day basis, every word infused with compassion and anger. Her frustration with the injustice and the lack of action being taken to help these children is moving. It’s accessible and outrage-inspiring without feeling preachy. And when we see the remarkable work she’s done in San Francisco to help treat the issue, it’s inspiring.

Redford’s interviews with researchers reveal that toxic stress can be reversed if children are given enough emotional support, and where possible, taken out of the dangerous situations they find themselves in. We follow some of the social workers providing this support, and the parents and children who are struggling but benefiting from these programs. Redford’s methods may be purely educational, but he makes it difficult to leave the cinema feeling anything but outrage and a desire to see and even be the change needed.

Resilience may seem out of place at a film festival. At times it seems, in style and content, more like a PBS special report than an example of innovative filmmaking. But documentaries have different purposes, and though the film’s structure is conventional, it is innovative in how it presents scientific information in a digestible fashion. We need more of that, and so I can’t help but find the film a success.