Documentarians Peter Middleton and James Spinney use segments of John M. Hull’s actual audio tape recordings to reconstruct his experience of going blind in this experimental nonfiction film.

Read all our articles on sound design.

In 1983, in his late forties, Australian theologian John M. Hull began to go blind. Grappling with the loss of his vision, he recorded a series of audio diaries, tracing his activities, reflections, and conversations, in an effort to understand his changing interaction with a world he could no longer see. Documentarians Peter Middleton and James Spinney use segments of Hull’s actual audio tape recordings to reconstruct his experiences in their experimental non-fiction film, Notes on Blindness.

Rather than tell Hull’s story from a distance, with talking heads as in a documentary, Middleton and Spinney attempt to embody Hull’s experience of blindness with the medium of film itself. The filmmakers experiment with both visual and aural elements, never presenting their audience with a clean slate of images. The film opens with close ups of a tape recorder. Hull’s recorded voice emanates from its speakers, “testing, testing,” encouraging the viewer to concentrate on the film’s aural composition. Then, a long close-up of a bloodshot eye represents Hull’s disappearing sight, but it’s not the voyeuristic eye of Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Faced with an unseeing eye, the audience is encouraged to privilege listening, rather than settle for what we might struggle to see.

The film then slows down and proceeds with a hazy cinematic rhythm. This expresses Hull’s day-to-day struggle, assisted by the soft, grainy timbre of Hull’s voice. The film often resists clarity and sometimes meanders to the point of tedium, stressing that our eyes can’t always answer all questions. Through isolated sounds and fragmented visuals, the filmmakers explore key events in Hull’s life, like the birth of his son and a holiday to Australia. These events are interspersed with mundane images like hands brushing against a staircase bannister and turning through pages of a book, made aurally vivid through amplified sound effects. Actors Dan Skinner (John) and Simone Kirby (John’s wife Marilyn) lip synch to the recordings on screen, while other characters are seen only partially or out of focus, encapsulating Hull’s fragmented grasp of the world in the film form itself.

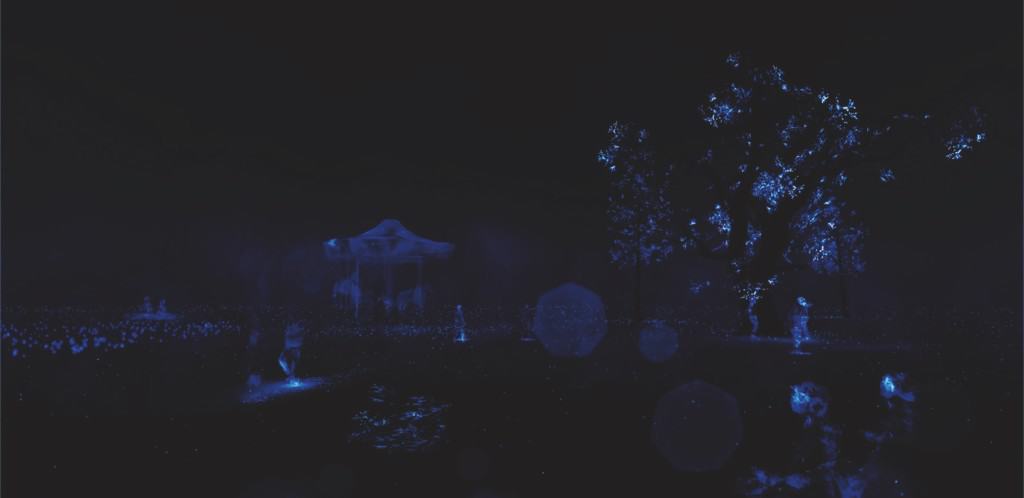

Yet these sustained obfuscated visuals are a discomforting, physically painful experience, which help the viewer associate more, even temporarily, with the state of blindness. Hull finds something poetic about blindness: as though consciousness is evacuated and the other senses take over. But this experience isn’t easy. After narrating the visual experience of his dreams, Hull says, “Every time I wake up I lose my sight.” The brain thirsts for what it is accustomed to, Hull reflects. As a man who once had sight, he constantly lives with that thirst. Hull says that, as a blind person, he feels like “a ghost inhabiting a building,” and I almost felt this way as an audience member — as though I were a ghost-like part of a film, offered only fragments of sensations, not quite allowed to participate.

The festival’s New Frontier section where the film screened included a related virtual reality project, Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness, which also aims to take participants to a world “beyond sight”. It relies on imprints of objects and phenomena in a pitch black virtual environment to anchor the surrounding sounds, and my ears were treated to environmental phenomena as sound before images. Ironically, my eyes ached during the experience — perhaps another correlation with the process of going blind.

Significantly, the film’s aural landscape brings a new dimension to Hull’s words, from his audiotapes to his book Touching the Rock. In this respect, the film carries on Hull’s legacy by expanding on his valuable contribution to the discourse of sensory phenomena. Notes on Blindness traces a distinctive path, but it is hard to say whether an experimental film like this will attract audiences not already familiar with Hull’s work. It ends with images and sounds replicating the soothing resonance of sea swell and waves lapping against the shore — perhaps some of Hull’s favorite sensations. These final moments work well for the film’s thesis: there is a potential ocean of sound out there, and we just need to listen.