Though he’s made films in English, French, and Dutch, Matthias Schoenaerts tends to communicate his characters’ inner lives through physicality rather than dialogue. This is the 4th feature in our special A Bigger Splash week.

Read our features on two of the film’s other leads: Dakota Johnson, and Tilda Swinton. Read our review of the film here. Read our interview with director Luca Guadagnino here.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

The polyglot actor Matthias Schoenaerts isn’t much one for speaking. Though he’s made films in English, French, and Dutch, he tends to communicate his characters’ inner lives through physicality rather than dialogue. Much of his work tends to focus on his characters’ relationship to their bodies. Tall, muscular, broad-shouldered and ruggedly handsome, Schoenaerts is the physical embodiment of conventional masculinity, but he tends to choose parts that actively interrogate what masculinity is and how it can be toxic to men.

Schoenaerts finally garnered international acclaim as the cattle farmer Jacky in Michaël Roskam’s Oscar-nominated Bullhead (2011). When we meet him, he’s a fairly threatening presence, walking clunkily, head jutted forward leading his body. But there’s a vulnerability despite his brusque manner, most obvious when he visits the pharmacy where a woman he likes works and finds himself tongue-twisted and awkward. Flashbacks tell us about his tragic childhood, when a bully smashed his testicles, leaving his body forever damaged and on an overcompensating regime of testosterone.

Suddenly, the foetal position in which he bathes, his excessive yet uncertain aggression all makes sense: he’s spent his life trying to overtly flaunt his masculinity. The parallels the film draws between Jacky and the cattle he cares for are on-the-nose: he earns the film’s title in one scene when he bangs his “bullhead” against another man as a threat. Bullhead may not be a particularly nuanced critique of conventional masculinity, but it does situate Jacky’s aggressive behaviour as an active performance. The role marks the beginning of Schoenaerts’ exploration of masculinity that has carried through all of his roles since then.

Whereas Bullhead was about Jacky’s dysfunctional body, Jacques Audiard’s Rust and Bone (2012) explores Schoenaerts’ relationship with his extremely functional body. His character Alain is a mess: he’s a careless father who has recently become a single parent, with a tendency to be gruff and crass. When he first meets Stéphanie (Marion Cotillard) at a club, he accuses her of being dressed like a slut to invite trouble. Intelligence and words are not his strong point. But when Stéphanie loses her legs in a brutal accident, she somehow senses that Alain may be just the right companion for her, and she’s right.

Whereas most people are uncomfortable with Stéphanie’s new disability, apologizing or pitying her, Alain can’t be bothered. Any physical problems she may encounter seem inconsequential to him. If she needs to get into the water to swim, he can carry her. When he’s around, she needn’t pull herself to the washroom with her arms; he can carry her there. He can help her without playing the martyr or the saint. And he can do it silently, since he can rarely find words anyway. He has an almost transactional relationship with his body, considering it “operational”, and it allows him to start an almost business-like sexual relationship with Stéphanie. In the rest of his life, he’s kind of a dick, but here, this comfort with his body helps Stéphanie find comfort in her new physicality.

After seeing Schoenaerts in Bullhead and Rust and Bone, Alice Winocour wrote Disorder (2015) specifically for him. Winocour describes Schoenaerts as having an “animality,” noting that “he really immerses himself into the part.” In Disorder, he plays Vincent, a physically damaged soldier whose value is in having a functional body – he works in security while on leave — but whose PTSD constantly threatens his sanity. He’s haunted by war, spending much of his time alone physically bent at the head or the waist. He’s lost the ability to take up space. In his black security outfit, he fades into the background, making himself as inconspicuous as possible even though his handsome good looks should make him stand out. It’s as if he’s slowly disappearing because his body has betrayed him.

But Vincent is still a terrifying presence, and an often hyper-competent one. He unleashes his pent-up anger with very little control. He’s physically intimidating in his size and carriage, even if he knows he’s falling apart. He spends most of the film taking care of the wife (Diane Kruger) of a rich criminal. The mechanical way in which he scans for predators, checks her for safety, and twists his head at even the slightest odd sound show the remnants of a highly capable soldier.

Though Schoenaerts began his career playing dumb physical specimens in Bullhead and Rust and Bone, his Vincent is much more intelligent. But his physical prowess helps others easily mistake for a fool, for the help, which is exactly how his charge treats him at first. It’s not until they’ve shared terrifying experiences together that they even exchange names. His body may make him a killing machine, but he spends both films trying to work out why his charge is being targeted, while developing tender and lustful feelings toward her. Once again, Schoenaerts may look like the manliest man; nevertheless, his Vincent wants to be seen for his other qualities, and he’s deeply vulnerable.

Schoenaerts’ most conventional foray as a leading man was as Gabriel Oak in Thomas Vinterberg’s decidedly feminist Far From the Madding Crowd. His character may be living in the 19th century, but Schoenaerts is very much a 21st century dreamboat. In his loose shirts, scruffy beard, and formal, restrained manner, Schoenaerts’ Gabriel emanates warmth. This is his golden retriever role: loyal, steadfast, smart, and beautiful. As a skilled farmer, he’s a man of the land, always seen on foot, making large, purposeful strides forward. He has to manage a careful shift in status, starting off as a man who proposes to a woman beneath him who later finds himself in her employ. Schoenaerts’ Gabriel never loses his pride, but he doesn’t shy away from deference.

The way Gabriel asserts himself and his affection towards his mistress, Bathsheba, is respectful, subtle, and physical. When one of her staff threatens to undermine her, Gabriel takes a small step forward, readying himself to come to her rescue. When Bathsheba marries, effectively making her husband the head of the farm, Gabriel’s instinct is to talk to her first, ignoring her husband’s newfound stake in the land. The way Schoenaerts bends his head down to level with Bathsheba, sometimes necessary just to find his way into the frame, is a small gesture of kindness. He may be a strapping young man, able to social climb through his skills with his body and the land, but he is always gentle with her. He chooses his words carefully, only offering her an opinion when he thinks he might be helping her, ready to be silenced if she isn’t interested.

Schoenaerts’ English-language supporting roles have been versions of the roles he’s already played. In The Danish Girl (2015), he’s a reserved businessman and art enthusiast who retains the warmth and kindness of Gabriel. In A Little Chaos (2014), he plays an aristocratic dreamboat who, like Gabriel, falls for an intelligent, independent woman, whom he treats as his equal. And in The Drop, directed by Roskam of Bullhead, Schoenaerts reprises his roles as a violent, volatile meathead.

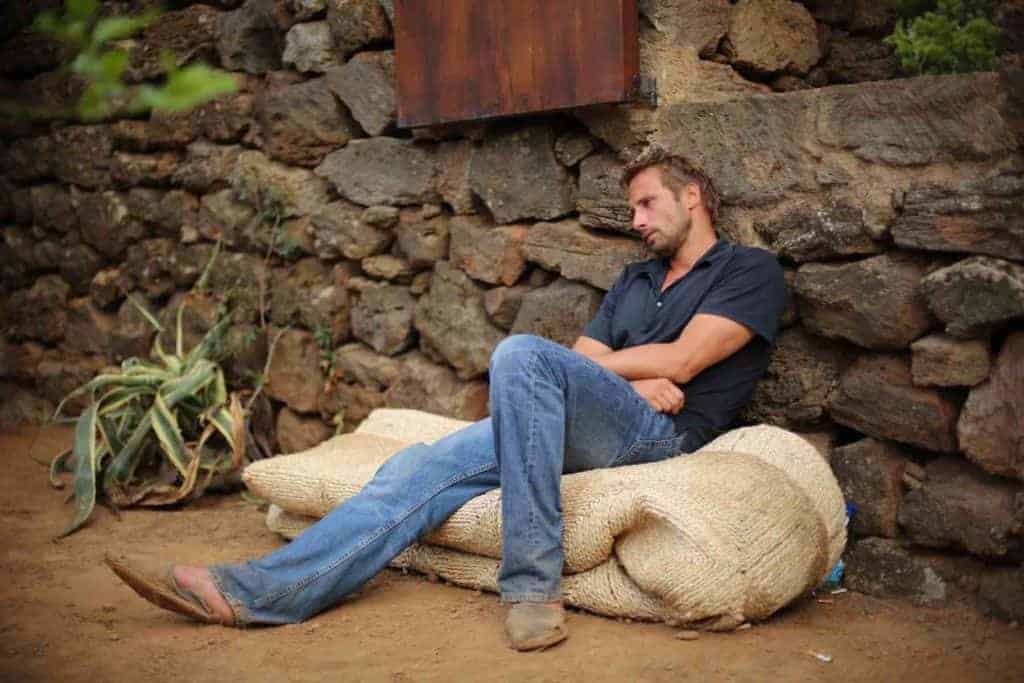

It wasn’t until A Bigger Splash that Schoenaerts had the opportunity to merge the visceral roughness of his French and Dutch parts with the quiet openness of some of his English leading men. As Marianne’s younger boyfriend Paul, he seems like an ideal of domesticity: he takes care of her; he’s drama-free; he’s quiet, depressive, and introspective; and he looks good in a ratty t-shirt, or nothing at all. As a documentarian, Paul values authenticity above all else.

Paul is the polar opposite of Marianne’s ex, the more age-appropriate Harry (Ralph Fiennes) who bursts into town to stir up trouble. Where Harry is a performer, constantly looking for the spotlight and stirring up shit, Paul does his best to hold his tongue. Harry infuriates him, but he tries to maintain decorum. The way that Harry wakes up Marianne, turns her on, and gets her excited intverts our expectations: Harry is older and crass, while Paul is younger and reserved, yet Marianne seems to orbit around Harry rather than her hotyounger man. Paul’s inability to deal with this near-usurpation causes him to lean into his baser instincts, pushing their story into darkness. If Paul starts out with quiet confidence, by the end he’s twitchy and worried, uncomfortable and anxiety-ridden.

The buff, stolid Paul ends up a young man with the burden of the world on his shoulders. It’s an inversion of Schoenaerts’ earlier roles: ruggedly physical young men whose bodies do most of the talking. In A Bigger Splash, Schoenaerts echoes his earlier roles but with a darker ending. Instead of letting his body bear the character’s burden, it’s Paul’s anxiety that betrays him.

More from A Bigger Splash week

Read our review of A Bigger Splash.

Read Dave Crewe on how Dakota Johnson challenges Hollywood femininity.

Read Kyle Turner on the queer cult stardom of Tilda Swinton.