Employing key but subtle twists on the convention talking head documentary, Ava DuVernay’s 13th explains how slavery in the U.S. was never really abolished without ever resorting to preaching.

It’s not until nine minutes into Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th, charting the history of slavery and mass incarceration in the U.S., that the first chyron flashes on the screen. Up until then, DuVernay has presented us with a handful of unidentified, mostly black voices. They’re explaining how the American economy was built on the exploitation of black bodies. Without flashing their credentials at us, we must evaluate what they say for ourselves, without the help of the academy — the mostly white establishment — to validate what we’re hearing. Their refined accents, clear diction, and sharp suits may suggest authority and education. But DuVernay wants us to actively think about how we decide whom to listen to and why.

This long delay before telling us, explicitly, that she’s interviewed experts, is just one of DuVernay’s many subtle ways of flipping the “talking head” documentary on its head. She does so with several purposes: avoiding any form of preaching; confronting us with our prejudices by withholding information; and giving dignity and weight to people, work, and stories that are too often dismissed, degraded, and forgotten.

A history of slavery after so-called abolition

Starting with the passing of the 13th amendment, DuVernay traces how a loophole in the law — that criminals may still be subject to slavery — has been exploited throughout the years right up until present day. Slavery was never really abolished so much as given another name. Imprisoning African Americans has allowed private industry, both those providing service to prisons and contracting cheap labour from prisons, to continue to profit off of black bodies.

These aren’t your average “talking head” interviews

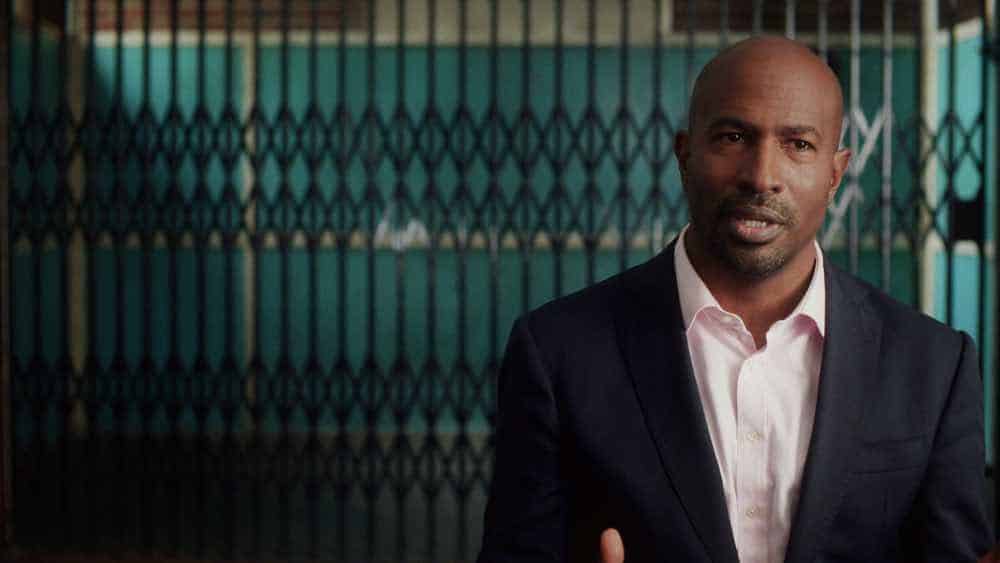

These aren’t your average “talking head” interviews that we’ve been conditioned to easily tune out as preaching or fact delivery. DuVernay shoots her subjects in profile, often with a moving camera rather than providing direct address into lens. The cinematic grammar is as vivid and alive as DuVernay’s subjects’ voices. We can hear their passion and indignation in every sentence. It gets us to listen because we don’t feel like we’re being forced to.

DuVernay often opts for wide shots that create dramatic compositions rather than framing her talking heads in medium shots or closeups. These imbue her subjects with dignity and link their words with memorable images. Consider Michelle Alexander, whom we see speaking from a red armchair against a tall window. She may be at the bottom of the frame, but the image calls to mind a throne. It’s a subtle way of crowning her subject, hinting at us that she’s important without using the usual documentary cues like immediately listing credentials. Instead, DuVernay gets us to look at her subjects like characters, or perhaps more accurately, like individuals with whom we can empathize.