Sebastián Lelio’s A Fantastic Woman follows a grieving transgender widow who fights for her right to be respectfully treated as a person in mourning. Read our interview with Lelio about the film.

Until very recently, transgender characters remained in the margins of mainstream cinema and TV, often depicted as ugly caricatures while relegated to a bit part, best friend character, or grossly insensitive punchline. By contrast, films like Sean Baker’s Tangerine (2015) and the TV show Transparent (2014–) have embraced transgender characters as leads. Such instances remain so rare that the choice to tell their stories at all is still perceived as a political act. Nevertheless, the presence of transgender characters in media is more than merely a political statement or something confrontational and transgressive. For true equality, it’s important to treat transgender characters as people who aren’t entirely defined by their gender.

Read more: Writer-director Sean Baker talks Tangerine >>

This is not, of course, to deny the specificity of their experience. Sebastián Lelio’s A Fantastic Woman, a favourite of this year’s Berlinale competition, at first seems to be downplaying its lead character’s gender identity. It’s almost as if the film were attenuating this still rather uncommon trait in a lead character to avoid scaring off skittish audiences. Yet in the end, A Fantastic Woman proves a subtle and poignant statement on what we accept as ‘normal’.

[clickToTweet tweet=”A Fantastic Woman proves a subtle and poignant statement on what we accept as ‘normal’.” quote=”A Fantastic Woman proves a subtle and poignant statement on what we accept as ‘normal’.”]

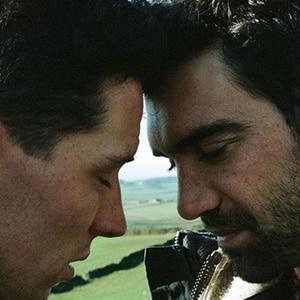

Transgender actress Daniela Vega plays Marina Vidal, a transgender woman who is in a conventional heterosexual relationship. The film opens with a commonplace ritual: Marina and her partner, Orlando (Francisco Reyes), celebrate her birthday with a present, a big cake, and a serenade at a nice restaurant. Orlando and Marina live together in a lovely flat: they are the picture of domestic bliss in the most cliched, archetypal sense.

That Orlando is old enough to be Marina’s father does not function as a narrative device only — his death by aneurysm is what sends Marina’s life spiraling down and triggers the film’s narrative. It is also a nod to changing mores: once a taboo, being with a much younger woman is now relatively destigmatized, even an enviable situation for many aging men. However, that Marina can be both the cliche of the younger girlfriend, and a transgender woman, knocks down the entire house of cards of current cultural mores. Her relationship with Orlando establishes a new ‘normal’ where one can simultaneously be transgender and in a conventional heterosexual relationship.

Read more: Director Alexandra Therese-Keining talks Girls Lost and gender performance >>

Marina’s gender identity inevitably turns her relationship with Orlando into a powerful statement against oppressive values. Yet this political aspect of their relationship — the way it is defined by the outside world — is not the focus of the film. Instead, Lelio makes a point of letting us experience it as natural, seamless and unstigmatized, from the insider perspective of two people who simply love each other. Rather than focusing on Marina being transgender, the opening of the film is all about showing Orlando’s desire and affection for her. A series of close ups continuously highlight the way he longingly looks at her in every scene.

Yet when Orlando dies, Marina’s gender identity is suddenly brought to the fore as the film’s topic, when others start to treat her like a “freak”. Lelio’s film follows her as she resists those who try to reduce her to her gender identity and fights for her right to be respectfully treated as a person in mourning.

[clickToTweet tweet=”A FANTASTIC WOMAN reveals how institutions can turn against the people they are meant to protect.” quote=”A FANTASTIC WOMAN reveals how institutions can turn against the people they are meant to protect.”]

Scenes of confrontation between Marina and the various transphobic people she meets reveal how institutions can enforce oppressive values and turn against the people they are meant to protect. As soon as her partner dies, doctors imply that Marina was somehow responsible. Taken aback by this transphobic hostility minutes after she has just lost her lover, Marina flees the hospital. Her reaction should not be surprising to anyone with even the slightest conception of the hostility that transgender people are still subjected to. Yet even the police turn against her, having the audacity to claim that they are just following normal procedure when it is painfully obvious that they are gleefully acting on prejudice.

Read more: Francis Lee discusses his Sundance Directing Prize Winner God’s Own Country >>

Whether she is forced to endure an unnecessary physical exam to satisfy a doctor’s curiosity, or confronted with the open hostility of Orlando’s family, Marina remains quiet and dignified. When Orlando’s ex-wife tells her that she is a ‘chimera’, or when Orlando’s brother calls her a “faggot”, Marina never once replies with the obvious: an explanation about how she feels better that way, and they should respect her choice. She doesn’t feel compelled to explain herself to anyone. Yet her silence is not submission, but rather a sign of the respect she has for herself.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Marina has constructed her life around a few havens of peace.’ – @elazic” quote=”Marina has constructed her life around a few havens of peace.”]

Instead of wasting her time seeking the acceptance of those who should not need persuading, Marina has constructed her life around a few havens of peace. By simply showing her categorically refusing to engage with transphobic people, even when she really wants to, Lelio subtly hints at a the whole history of his character. This self-control, and the casual way in which she drops by the places of a select group of friends, show just how much time she has spent fine-tuning her survival strategies and finding safe spaces —which can be scarce in the city of Santiago, Chile.

Read more: Top 5 film performances of 2016 that deserve a closer look >>

The scenes where Marina is faced with hateful people are all the more powerful, maddening and unsettling because like them, Marina espouses a decidedly conventional lifestyle. Were these people to accept Marina’s choice to transition — to accept her for who she is — they just might find they have quite a lot in common with her. However, the main difference between these two opposing views is not so much physical as it is moral. Unlike Orlando’s family, the policewoman, and the hospital staff, Marina knows and accepts that no gender, sexual orientation, or lifestyle is ‘normal’. Rather, they are all constructs: aspects of identity which are all as unique as people are, with as many variations to them as there are individual experiences.

[clickToTweet tweet=”Marina refuses to be a victim of transphobia and rejects the role of the mourning widow.” quote=”Marina refuses to be a victim of transphobia and rejects the role of the mourning widow.”]

Marina’s adoption of a normal heterosexual lifestyle is not an effort on Lelio’s part to make his character more familiar or less ‘scary’ to a cis-audience. If anything, it makes Marina less likeable to those like Orlando’s family. Faced with a person who once had the body of a man yet is now living as a heterosexual woman, they are forced to realise that heterosexual roles are not in fact innate or ‘normal’, but highly flexible constructs. A sequence that shows Marina in a gay club, giving a blow job to a stranger then dreaming of herself in a sparkly outfit vogueing with the crowd, strongly suggests that she once led a very different life. This did not prevent her from later settling down with Orlando and choosing a lifestyle remarkably similar to those around her.

Marina only sheds a few tears when Orlando dies, a heartbreaking early sign of the strength she has had to develop in the face of unfathomable adversity. It also shows her clear-mindedness and independence. Just as she refuses to be a victim of transphobia, Marina rejects the role of the mourning woman that society expects her to adopt. She is not a tragic character whose existence was entirely defined by a man. She fights to see Orlando one last time not because of some romantic, monogamous notion of being bound forever, but to say goodbye to her partner so that she can move on with her life. Lelio’s profoundly sensitive film does not end with Marina’s pain, but with Marina trusting herself even more than before, singing opera on stage to an audience for the first time. It is an uplifting ending which foregrounds Marina’s journey towards the happiness she deserves rather than the bigotry of the world around her.

Read our interview with Lelio about the film >>

Keep reading about great queer cinema…

Call Me by Your Name

Read Call Me by Your Name: A Special Issue, a collection of essays through which you can relive Luca Guadagnino’s swoon-worthy summer tale.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Read our ebook Portraits of resistance: The cinema of Céline Sciamma, the first book ever written about Sciamma.

God’s Own Country

Read God’s Own Country: A Special Issue, the ultimate ebook companion to this gorgeous love story.