Directors Neasa Ní Chianáin and David Rane discuss their documentary film In Loco Parentis about a modern boarding school, Headfort School in Ireland.

Neasa Ní Chianáin has continued to explore innovative pedagogy on film with her documentary Young Plato.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

Outside the village of Kells, in County Meath, Ireland, lies an unexpected utopia: the 200-year-old Headfort House, which is home to Headfort School, a thoroughly modern teaching institution. Here, a group of 80 children from around the world, between the ages of seven and thirteen, live, learn, make lifetime friends, and thrive under the care of 20 staff.

During the day, they attend classes where teachers inspire debate and discussion. In the afternoons, they build forts in the forest that surrounds the school. And they find their passions in a wealth of extracurricular activities, from sports to music to drama. As a boarding school, Headfort operates with the “in loco parentis philosophy”: it’s the teachers’ full time job to not just teach but also care for all of the students’ emotional needs.

Neasa Ní Chianáin and David Rane sent their kids to Headfort, which sparked the idea for the documentary School Life

A few years ago, documentarians and partners Neasa Ní Chianáin and David Rane decided to send their children to board at Headfort. “We were really impressed by it because it focussed on the whole child and the happiness of the child,” recalled Ni Chianáin. It soon became clear to them that the school would make for an interesting documentary about the “modern day 21st century boarding school”. “Our kids were there for a year before we shot anything,” added Neasa Ni Chianáin. “We were able to gauge the effects that it was having on them. It was overwhelmingly positive. They just loved it.”

“Both David and I had been to boarding school when we were kids,” explained Ní Chianáin. “We had very different experiences. I went to a school similar to Headfort as a day pupil when I was four. And then I packed myself off to boarding school after that. It seemed great. I went to boarding school when I was 11, and I had a really nice time.” “I had a more difficult time,” recalled Rane. “My parents were working in Nigeria. They sent my brother and I back to England to boarding school when I was seven. That was a big separation and quite difficult for a seven-year-old.”

Setting up shop at Headfort and getting started

To make the film, Ní Chianáin and Rane set up shop in a “small little office that was down in the basement” of the school. They shot for two years. “We were there all the time. Sometimes, we stayed overnight in the school if we were shooting late at night or early in the morning,” Neasa Ní Chianáin added. “We knew we had to disappear as we were working with children. We didn’t want to be the focus of attention when we started shooting. So we made sure that we were very visible in the school all the time. The children got used to us. They just got on with their daily routine. We were no longer a novelty.”

“We took the project to various development labs which finessed it and sharpened it,” recalled David Rane. “But we were never really sure until the first few months of filming who would emerge as characters and storylines. It was fascinating to prepare and plan an observational documentary where you’re going to just allow what happens in front of the camera to be in your film. It was a revelation, a joy, and a real discovery.”

Download the first two ebook chapters FREE!

Explore the spectrum between fiction and nonfiction in documentary filmmaking through films and filmmakers pushing the boundaries of nonfiction film.

“We were trying to capture the essence of the school to do a year in the life,” explained Ní Chianáin. “The footage we used was from the second year, more for coherency of storytelling than any other reason. We decided we would follow positive story arcs — only if it became positive at the end. We didn’t want to capture a child, suspend them forever in film as a particular thing, and leave them unresolved. So we had to cast the net quite wide for filming with children. Nobody knew who we were focusing on. We did that consciously because we didn’t want a child to carry that kind of pressure either.”

Read more: Writer-director Selma Vilhunen talks Little Wing >>

In the end, the filmmakers decided to focus the narrative on three students and three teachers: the headmaster, Dermot Dix, and John and Amanda Leyden, the husband-and-wife team who have been teaching at the school for decades. Dix is “a progressive, left-wing teacher”, as well as a Headfort alumnus and former student of the Leydens. Dix spent many years teaching at the Dalton School in Manhattan, another school with innovative pedagogical practices. He brought that experience back with him to Headfort to help shape the school.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘A lot of schools talk about the surrogate family. But we genuinely found it.’ – Ní Chianáin” quote=”‘A lot of schools talk about the surrogate family. But we genuinely found it.’ – Ní Chianáin”]

Headmaster Dermot Dix and how he gets the students to share opinions

I was struck by how candid Dix was with his students when leading class discussions and debates about controversial subjects, such as same-sex marriage and breaking immoral laws. He always treats his students with respect, never talking down to them, and he’s unafraid to express his opinions. The school is nondenominational. But it still came as a shock when he reminded his students that we don’t have proof that there is a god. Even entertaining that possibility was taboo in my day.

Read more: Breaking boundaries in Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women >>

Finding protagonists in the Leydens for the documentary School Life

It wasn’t until the second year of shooting that the Leydens emerged as the sort of matriarch and patriarch of the school and the film’s protagonists. “A lot of schools talk about the surrogate family,” said Ní Chianáin. “But we genuinely found it. This was a surrogate family.” When Rane and Ní Chianáin spoke with alumni, the Leydens would be mentioned most often. They were the teachers who had really “left their mark on them.” The film actually begins in the Leydens’ house to which, Ní Chianáin recalled, “There was a well-beaten track. There could be a 50-year-old coming to visit them, a 20-year-old coming to visit them. [They were] all ex-pupils who really did bond with them on some level. We thought this was quite extraordinary.”

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘We suddenly realized the importance of switching a child on as early as possible.’ – Ní Chianáin” quote=”‘We suddenly realized the importance of switching a child on as early as possible.’ – Ní Chianáin”]

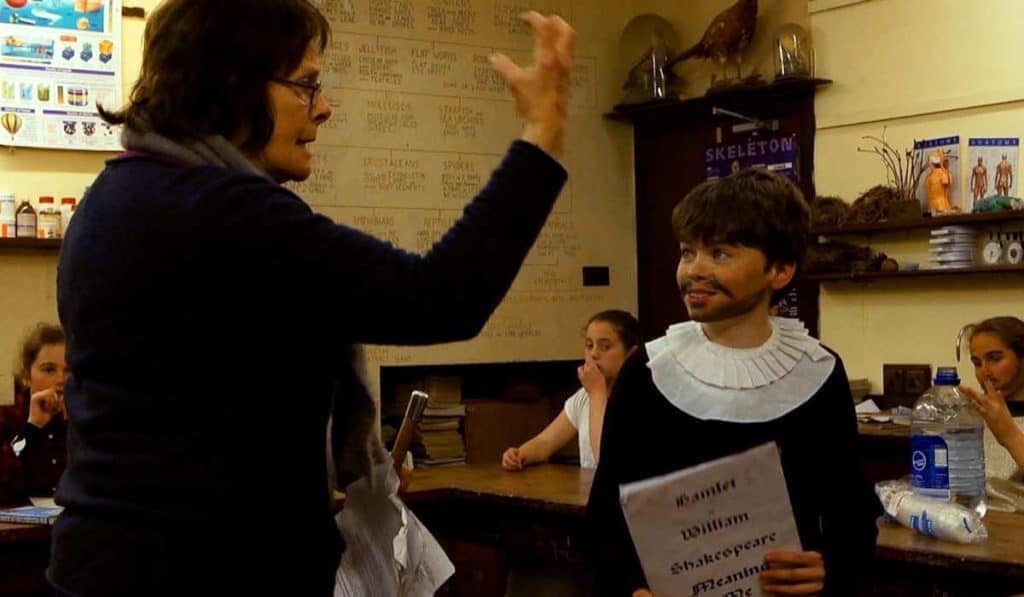

Amanda Leyden teaches English to all of the students at the school. The film captures her classes with students of different ages, showing us how she gets them excited about reading and stories. One of the most exciting subplots involves Amanda Leyden’s class preparing to put on a play. They fumble through rehearsals, and finally perform to rapturous applause from their audience of fellow classmates. One of Amanda’s students, Ted, had dyslexia, but as a performer, he really thrived.

Download the first two ebook chapters FREE!

Explore the spectrum between fiction and nonfiction in documentary filmmaking through films and filmmakers pushing the boundaries of nonfiction film.

School was about more than academics

Ní Chianáin reflected, “It felt like a school where if you weren’t academically gifted, it didn’t matter. There was somewhere. You were going to find it in sports, in acting, in the art room. You were going to find something that you were good at. That’s something that we really admired in the school, that there was that space for the child. It didn’t always have to boil down to academics.”

Read more: Writer-director Chloé Robichaud talks Boundaries and women in politics >>

John Leyden’s band

The extracurricular band that John Leyden ran really captured their attention. It’s a great example of how the teachers act as parents, taking care of the children’s emotional well-being. “We were really taken by the band room and how that worked,” recalled Ní Chianáin. “You audition as a musician. If you weren’t a musician, you had a chance to be a painter. If you didn’t cut it as a painter, you could be a carpenter. And if you didn’t cut it as a carpenter, you could be a cleaner. So kids would come in at the cleaner stage, and by term one, they’d start messing around with either painting or an instrument. Usually, they’d climb up the ranks. They organized that themselves. They learned responsibility.”

Early in the year, John made it his personal project to help one of the eldest students, Eliza, open up socially. Although she was an incredibly talented student, she had difficulty speaking to other people and coming out of her shell. John took her on in the band as a keyboardist. Through integrating her into the group, he helped her to blossom. By the end of the year, she was making conversation with all of her classmates, a real social butterfly.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘We were constantly trying to find the emotion to the story.’ – Ní Chianáin. ” quote=”‘We were constantly trying to find the emotion to the story.’ – Ní Chianáin. “]

Editing the film

When Ní Chianáin and Rane started to edit the film, they had compiled about 400 hours of raw footage. Their first step was to narrow it down to the best 25 hours. Then, they figured out how to craft a narrative from it. “We were constantly trying to find the emotion to the story,” explained Ní Chianáin. “That took a long time because one scene affects another scene. It can be more emotional depending on what came before it. It was a process of trial and error. We did a lot of audience testing to see, ‘is this an interesting story? Does this sustain its way all through the year?’ Based on that feedback, we listened to that.“

Read more: Review: Francis Lee discuss his Sundance Prize Winner God’s Own Country >>

Rediscovering the joys of school

After watching the documentary School Life, I felt like I wanted to go back to age seven and relive my childhood at Headfort School. So I had to ask, “Is the school really as much of a utopia as it seems?” Although Rane assured me that Headfort has the same problems as most schools, including the occasional incidence of bullying, their experience — as filmmakers and parents — was overwhelmingly positive. The brief period of homesickness that the younger students feel when they begin their studies quickly turns into “the sadness of leaving school,” said David Rane. During the time they shot the film, only two students chose to leave the school early.

[clickToTweet tweet=”If you invest in children and give them a happy, safe space to be free, they will thrive.” quote=”If you invest in children and give them a happy, safe space to be free, they will thrive.”]

A new perspective on early education

Making the documentary School Life gave Neasa Ní Chianáin and David Rane a completely new perspective on early education.“We suddenly realized the importance of switching a child on as early as possible —” said Ní Chianáin. “Keeping them engaged, and the importance of great teachers who can engage them, and make education a very positive experience,” added Rane. “And fun experience!” Ni Chianáin concluded, “If you invest in children and give them a happy, safe space to be free, they will thrive.”

Read more: Interview: Kasper Collin discusses the making of his Lee Morgan doc I Called Him Morgan >>

Become a Seventh Row insider

Be the first to know about the most exciting emerging actors and the best new films, well before other outlets dedicate space to them, if they even do.