Director Kyoko Miyake talks Tokyo Idols, how the girls stay safe, and how the inherent sexism in this subculture isn’t that different from life in the West.

Kyoko Miyake’s Tokyo Idols gets under your skin. The film examines the objectification of “Tokyo Idols”: young Japanese girls who are pop singers in girl groups. The most well known Tokyo Idols are a group called AKB148, which splits girls into different teams; in total, there are around 127 members each year.

Tokyo Idols are accessible pop stars who dress like school girls, with puffy short skirts and their hair in cutsy pigtails. Bizarrely, the majority of their fanbase are men in their early 40s. After their shows, they hold meet and greet events, “hand-shake events”, where fans can talk to them. In Japanese culture, the handshake is seen as an erotic gesture, which makes this fertile ground for sexually exploiting young girls. Nevertheless, the film shows that being a Tokyo Idol can actually be empowering. Kyoko’s prime example is Rio, a pop singer who had full agency over her choice to become an idol and pursue a career in music.

I talked to Kyoko about the Tokyo Idol subculture, how the girls stay safe, and how the sexism inherent in the Tokyo Idol culture isn’t that different from life in the West.

The Seventh Row (7R): What is a “Tokyo Idol”?

Kyoko Miyake (KM): It’s a cultural phenomenon, but it goes much deeper than that. It symbolises everything that made me uncomfortable being a woman in Japan. I remembered how awkward I felt growing up in Japan, as a girl. Whenever I wasn’t acting or being cute, people took it as a sign of defiance. [This] became very confusing. My personal starting point was this feeling, “Why do we always have to look cute, innocent, inexperienced, and immature? These are the only qualities that people [in Japan] admire in girls. How can you ever get independent [and] be strong?”

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Tokyo Idols symbolise everything that made me uncomfortable being a woman in Japan.’ ” quote=”Tokyo Idols symbolise everything that made me uncomfortable being a woman in Japan.”]

It started about 10 or 12 years ago with this [popular] band called AKB48. They were formed in 2006 or 2007. The whole point is that you can meet them, shake their hands, [and] you can talk to them. They are not these big stars that you can only admire on stage or on TV. No one was in it for the money. Not many people were making money. The parents were actually losing money [by] investing in their kid’s future. The most typical fan would be 42-year-old single man, who tends to be an obsessive type.

7R: How did you get interested in making a film about this phenomenon?

KM: I’ve been living away from Japan for the last 15 years, but I’m still there all the time. During one of my visits back home, I was watching TV, and I saw this red flashing sign, “Breaking News”. I thought it might be something about North Korea or the Middle East. It was about this idol girl graduating from AKB48, [which was] the biggest news for several days. I [thought], “What is happening here?” I also started to noticed in The Mainichi newspaper, which is like our New York Times: every year, they ran a series of articles [with] election predictions running up to the elections of AKB48. They had four or five experts on a panel to discuss who may do better this year. This is a progressive leftist daily [paper] that is running this series. It’s not just a niche thing.it’s mainstream culture [in Japan].

7R: Where did you begin your research, and how did you find your subjects for the film?

KM: The idol culture uses the internet as their platform. Initial contact was not too hard. The harder part was to find somebody who would open up but also show aspects of their life that aren’t really pretty. We talked to underground idols, like Rio, but also bigger bands, more successful bands that often appear on TV.

We soon realized that the bigger the management, the more restrictive the access was. The managers would say, “Don’t film the girls when they don’t have perfect makeup on. Don’t film them eating these sweets.”

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘We are trying to talk about objectification, but we are also in danger of objectifying them.'” quote=”We are trying to talk about objectification, but we are also in danger of objectifying them in our film.”]

We wanted to explore was the objectification of these teenage girls. It’s hard for teenagers to articulate what they are feeling or thinking. We are trying to talk about objectification, but we are also in danger of objectifying them in our film.

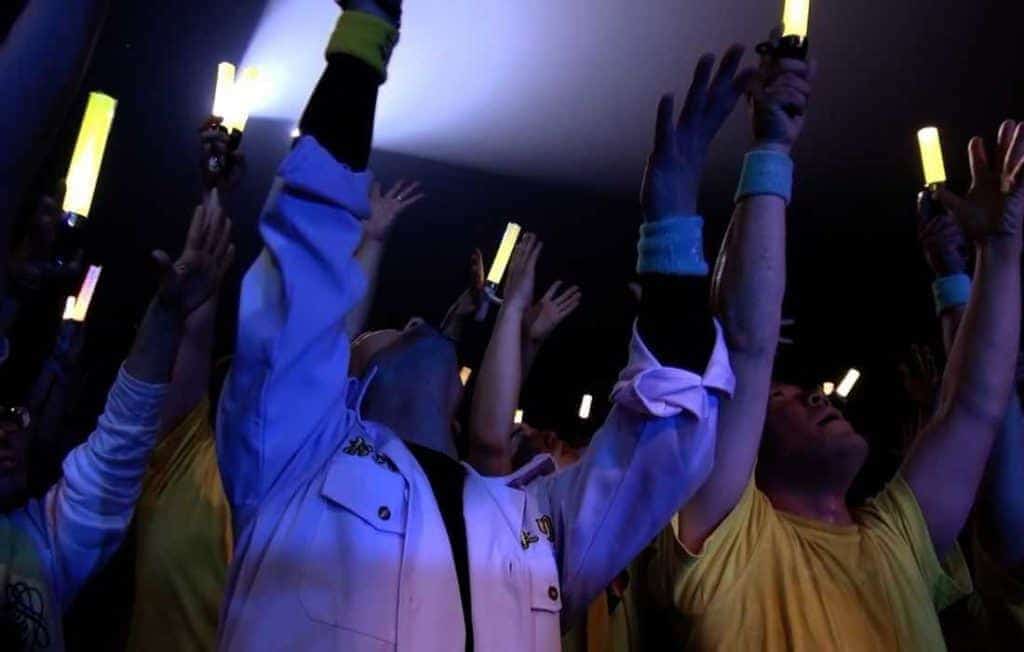

An idol concert consists of 15–20 acts, each act lasting about 15 minutes. We were only allowed to film the underground band that we had permission for at a very small event. We saw Rio performing. Rio and her fans really stood out, but we weren’t allowed to talk to them.

As we were leaving, she came running towards us. She said, “My name is Rio, and here’s my new CD. Do you want to talk to me sometime?” And then her manager came running after her. I loved the way she bossed him around. That’s when I thought, “We’ve found our girl.” Rio gave us full access. Rio is opinionated. She seemed to have more agency, I felt safer and more comfortable in her company than in other girls’ company. With Rio and her manager, I don’t think it was an exploitative relationship.

[clickToTweet tweet=”Tokyo Idol fan communities tend to work as self-policing communities. ” quote=”Tokyo Idol fan communities tend to work as self-policing communities.”]

7R: For the meet and greets, what safety measures are put in place to protect these young girls from these older men?

KM: I definitely don’t condone these type of events. My first impression [of an idol concert] was genuine surprise because the event was very clean. These events usually take place in a bar where they sell alcohol, but I didn’t see a single drunk person. The fan communities tend to work as self-policing communities. When one of Rio’s fan’s started to have romantic feelings towards her, when it wasn’t reciprocated, he became kind of aggressive with her. Other fans actually eliminated him from the community. They banned him from coming to any of the events.

https://seventh-row.com/2017/04/29/ann-shin-my-enemy-my-brother/

7R: What’s in it for the fans if they don’t get anything in return from these girls? Is it the energy of the concerts? The platonic relationships?

KM: It’s definitely the connection. These men live alone. One of them was an iPhone app developer. If he did not go to one of Rio’s concerts, he would spend the day not speaking to anybody. It was this sense of belonging. It was a very homosocial atmosphere. It was more about finding the peer group and doing all these [choreographed dance] movements together. They see each other three times a week.

Some of them had some sort of romantic feelings towards their idols. Maybe there was this virtual romance going on. A fan told me the whole point of an idol girl is [she’s] an average girl trying hard. You can identify with her struggle to get successful. The man could be the breadwinner and be the master of their household. The idol girl could tell you she’s only there because of [their] support. Maybe, outside, he feels like a failure. He doesn’t get a girlfriend because he doesn’t have a well paid job. But somehow, in the idol world, they can restore that loss of masculinity. Many of the idols songs are about how great you are the way you are.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘In the idol world, they can restore that loss of masculinity.'” quote=”In the idol world, they can restore that loss of masculinity.”]

Even though many fans know each other quite well — they see each other three times a week — they may only know each other by their online name, like their Twitter name. Sometimes, they don’t even know what they do during the day. This night persona gives them an alter ego. Between nine and five, they have this boring office job, but after 5 p.m., when they come to an idol concert, they become somebody else. It’s kind of liberation from their real world.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘We wanted to capture a sense of alienation in a big city.'” quote=”We wanted to capture a sense of alienation in a big city.”]

7R: Can you talk a little about the score and who you collaborated with on that?

KM: We collaborated with Canadian composer Dave Drury, who came on board quite early in the edit. We wanted the music to blend with the sounds of the streets that we captured and recorded. Tokyo is like an assault to your senses: constant jingles, bells, sounds, and traffic. Japan is full of those metallic electronic sounds. Dave and I discussed how to bring the audience into that sound universe.

HotDocs interview: Vaishali Sinha talks Ask the Sexpert and India’s answer to Dr. Sue

7R: What visual aspects were important to you when telling this story?

KM: I wanted to bring that feeling of being lonely and isolated in the middle of this huge crowd. You are surrounded by thousands of people, and you could still feel completely alone. We wanted to show people walking alone in a big crowd [in slow motion] and to imagine that each one of them might have this story of feeling of lonely. We wanted to capture a sense of alienation in a big city.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘This kind of objectification between men and women is happening all around us—not only in Japan.'” quote=”This kind of objectification between men and women is happening all around us—not only in Japan.”]

7R: What do you want an audience to take away from Tokyo Idols?

KM: This kind of objectification and alienation between men and women is happening all around us — not only in Japan but in many other parts of the world. It’s just taken to the extreme in Japan. The audience may think this is a very strange distant world. I’m now based in New York, and I spent 15 years in Britain: in both [of those] countries, this type of thing would not be allowed. It would probably [be] criminal. But at the end of the film, if they think, “Oh wait, this is actually happening all around us!”, and it starts a discussion, that would be great.

HotDocs Interview: Director Ali Weinstein dives into a community of Mermaids