We called his film sexist. He tried to destroy our credibility. This is a story of sexism in the film journalism industry.

On Friday, we, the editors of The Seventh Row, received a puzzling email. A director suddenly got in touch, six months after we published a review of his film, to tell us that the review we had published was “dishonest” and factually incorrect. He took six paragraphs to tell us that our writer not only wilfully distorted the facts, but “took advantage” of us, without once listing a single concrete problem he wanted us to address. He claimed he hadn’t read the piece that he found so offensive. This was his response to a female editor regarding a piece by a female critic, which argued that his film was sexist.

This is one particularly egregious manifestation of a systemic problem: the perils of writing (and editing) on the internet while female, and the pervasive sexism of the journalism, and film journalism, industry. The way this director engaged us was familiar: his tone was polite, but seemed intended to silence us rather than generate conversation. When that failed, this director resorted to making false statements behind our back to discredit us to our peers. Hitherto, we’ve ignored it and tried to weather the storm, but we finally realised we may have been doing fellow women critics a disservice by staying silent and thereby tacitly condoning this kind of behaviour. Here’s the whole correspondence, or at least as much of it as we have. Hopefully, this is a message to others who feel it’s appropriate to act this way: we see you. We won’t be silent in future.

After some thought, we decided to remove all names and identifying information from the correspondence. This does mean that readers can’t go and examine the review themselves to see how accurate this director’s assertions are. However, we didn’t want to be perceived as trying to use this situation to drive traffic to the review — and given how quickly his behaviour has escalated, we were also wary of what might follow if we publicly named the director.

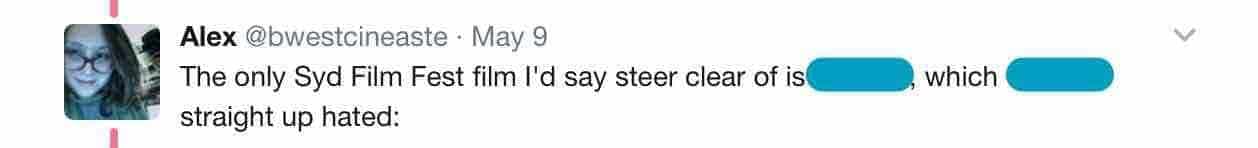

Almost two weeks ago, our editor-in-chief, Alex Heeney, was tweeting her recommendations for films to see at a festival. She rounded out her list by flagging one film that people might want to avoid. Our critic had objected to the film because she felt it was very sexist; her review was a sustained critique of the sexist stereotypes the film reproduced, and how these were reflected in broader film culture.

SOMEHOW, more than a week later, the film’s director found these tweets and took exception to them:

The redacted name in the second tweet above referred to a prominent male film critic who “really liked [the film] though”. Our critic’s piece, which Alex was referring to, is a sustained argument about the film’s misogyny and calls out how many male critics either didn’t recognize the misogyny or appeared willing to ignore it because they liked the film’s technical ideas.

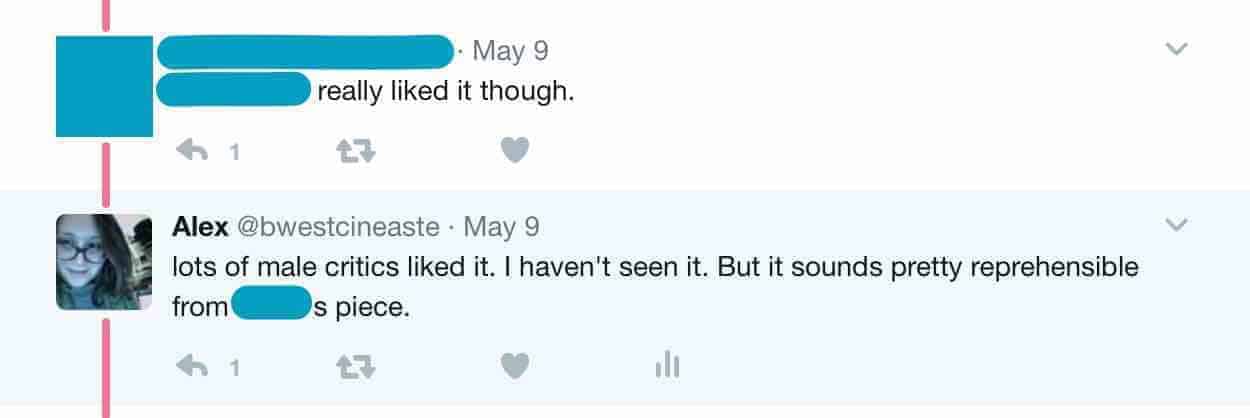

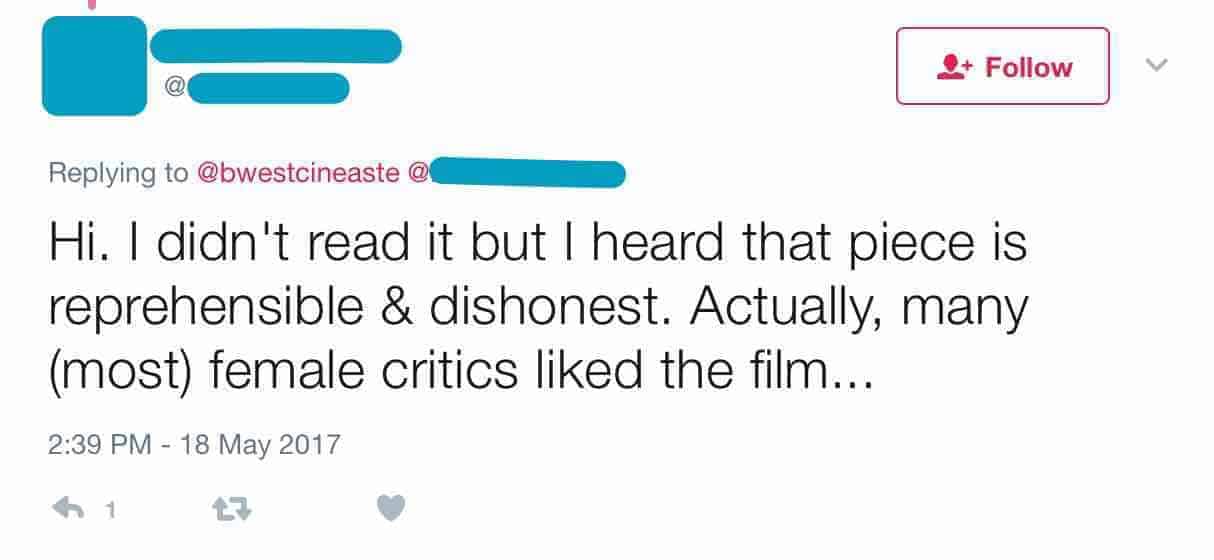

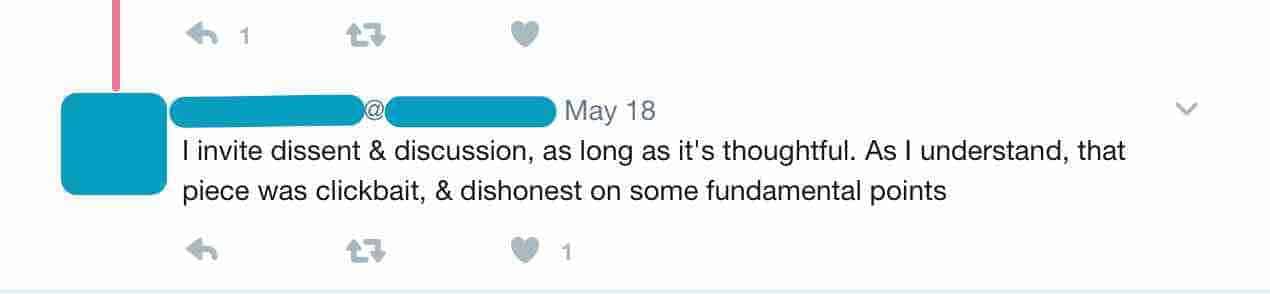

The director then provided links, in a series of tweets, to three positive English-language reviews written by female critics, as well as a link to an aggregate list of reviews in multiple languages.

This director is certainly entitled to point out that other female critics liked his film! But he led by calling a review he hadn’t read “reprehensible & dishonest”, without explaining why. OK, we can take the “reprehensible” part; after all, we said it first about his film. But if he says the review is dishonest, then he is accusing the author of serious factual errors or misrepresentation. We cannot address these errors if he doesn’t tell us what they are.

The next day, we received this:

From: [DIRECTOR] <[DIRECTOR]@gmail.com> Date: May 19, 2017 at 7:08:25 AM PDT

To: alex@seventh-row.com

Subject: [FILM]

Hi Alex,

Have you seen [FILM] yet?

If you see it, I would invite an open and thoughtful discussion with you about it.

I am no fan of bullying either. You will never see anything like that in my social media history.

And I would never engage someone with a negative opinion of my film to try to change their mind or intimidate them. That’s why I did not engage your writer at all. I would not want to send the wrong message.

I did want to correct a perception, however. You said that only male critics liked my film. I pointed out that there are plenty of female critics who liked it. I think I am entitled to correct that perception, right?

Apologies that I called the article, which appeared on your site, clickbait. I certainly appreciate sites such as yours that run with no advertising help purely out of passion.

At the time the article was published, our publicist read some passages from it to me, and it appeared that your writer misrepresented and distorted [FILM] to be able to better serve her agenda. This seemed fundamentally dishonest to me. I also believe that your writer personally does not like me, and the article was a way for her to execute a kind of revenge. Seeing the situation from afar, it appears she took advantage of you.

At the time, I wondered if you, as editor of the site, had seen the film, since there were also many factual errors in the piece. I felt it was sloppy and not worth taking seriously. But perhaps should have engaged you sooner to at least correct those factual errors.

Ultimately, I didn’t think it was worth dwelling on. And the film continues to go out into the world. There have been divided opinions about it, but rarely has the charge of misogyny come up. If it was a pattern at this point, I would have some real doubts and concerns.

At the same time… I’m reminded: our film was not made in a creative vacuum. There were many voices from the outside who weighed in at various points in the scriptwriting and production. Four of my producers are women. Our dear departed friend Chantal Akerman worked on the film. My editor is a woman. [ACTOR], the lead actress, wrote some of her own dialogue. I don’t know what, if anything, this proves. I’m merely putting it out there.

As I said at the start, I would enjoy a discussion with you. And I think you might find the film a bit more nuanced about the female perspective than the piece published on your site would indicate.

If you watch the film, and you think it’s total garbage, I would be happy to send you a check refunding you for the amount you paid to see it, along with a Criterion Bluray of your choice. If that doesn’t express to you my goodwill, I don’t know what will.

If you don’t feel like responding, you certainly have my guarantee that I won’t pursue this any further.

All the best to you and the future of your publication.

[DIRECTOR] (not a bully)

This director appears, at best, to be asking for a re-review because he didn’t agree with what our critic said the first time. At worst, he disparaged the integrity of a woman we respect by suggesting her review was motivated by “a kind of revenge”, without actually providing any evidence for his characterization of her work. This serious, unsupported personal accusation struck us as strange. The only concrete action he seemed to want was for us to see his movie, understand the error of our ways, and make amends. He would buy us a Criterion Blu-Ray if we didn’t see the light. He didn’t actually offer us a way to see the film now so we could fact-check it ourselves, or indeed give us any idea about what specifically we should be fact-checking. The review was published as part of festival coverage last year; the film won’t be released in theatres until later this year, in the fall.

The Seventh Row is a relatively small, niche, online publication. We have devoted readers, but we’re not a very big voice, and we don’t expect to have the influence on the industry that, say, Variety does. And, as this director has repeatedly pointed out, many other critics liked the film. So we didn’t feel that a response to the director or in public was necessary. We took him at his word when, in his second-to-last line, the director wrote, “If you don’t feel like responding, you certainly have my guarantee that I won’t pursue this any further.”

SPOILER: this was a mistake.

Yesterday, less than 24 hours after his previous email, a colleague forwarded the following email sent by the director to this colleague and to a group of critics and Film Twitter members:

From: [DIRECTOR] <[DIRECTOR]@gmail.com> Date: May 20, 2017 at 10:12:20 AM EDT

To: [DIRECTOR] <[DIRECTOR]@gmail.com> Subject: An Awkward request

Dear Friends,

If you’re receiving this, it’s because you follow a Canadian journal called The Seventh Row (SeventhRow) on Twitter (and perhaps also on another social media portal). You may also be following its editor, Alex (bwestcineaste).

Could you do me a huge favor and unfollow one or both (or whichever you happen to follow)? I’ll explain…

Last fall the site published a “hot take” on my film [FILM] that was irresponsible and full of factual errors. Our publicist contacted Alex to correct the errors but she never bothered to reply. A follow up email written by me was also ignored.

To give you a comparison, the Guardian also published a review that we didn’t like and contained factual errors, but their film editor, Catherine, was immediately gracious and even offered to print my letter in response.

The editor of the 7th Row, on the other hand, has offered no responsible form of arbitration. And to make matters worse, both the editor and the author of the article have taken to social media to unfairly denigrate me and my film.

I don’t know anything about either person. I’ve never read or followed their work. I’ve never really interacted with them. Perhaps there’s merit to other things that they have done or said. But I’m going to assume that they’re young, hungry for attention, and have decided to misguidedly use my film to help shape a larger agenda.

As my girlfriend put it, these are feminists who know nothing about feminism and give it a bad name. And to be clear, not Bad Feminists in the Roxanne Gay sense 🙂

If you “dropped” them from your social media lists, it would be a great gesture of solidarity with me and my film and I would feel a whole lot better about this situation.

If you choose not to, I also understand and you don’t have to justify yourself. I know this is a strange request. I’d also kindly ask that you please keep this between us.

If any of you are in Cannes, I hope to see you there in the coming days.

All the best,

[DIRECTOR]

We learned he sent similar messages to people friendly with our critic, which one person described as a “campaign” against the writer and the publication.

(We never received any emails from his publicist, either at the time of the review or since.)

So let’s recap: several months ago, we published an unfavourable review of this director’s film. No-one contacted us listing any “factual errors” in the review at that time or since. Earlier this week, one of our editors tweeted that based on our critic’s review, others might not want to see the film. This director responded by publicly calling a review that he had not read “reprehensible & dishonest”. Within seventy-two hours, after telling us he would let the matter rest if we chose not to respond, he had escalated to emailing third parties behind our backs and telling them our work is “irresponsible and full of factual errors”. He claims his publicist emailed us about these errors, but we can find no trace of such an email. This was his response to charges of sexism.

For a man who signs his email “not a bully”, it’s telling that he waited less than a day to start trying to destroy our reputation online. We gave his film a negative review because our critic thought it was sexist, and perhaps unwisely, we expressed our frustrations with this director’s Twitter comments and named the film when people on Twitter asked. But that’s far from the campaign this director appears to have initiated in response. How many other writers, and women especially, has this director bullied like this? How many people will he do this to in future if we don’t say anything?

We had hesitated to talk publicly about this, but the director himself made a review he didn’t like a public affair by contacting our colleagues intending to discredit our critic and damage our reputation. As a small publication, without industry clout or advertising revenue, all we really have is that reputation. It’s what allows us to get accredited at festivals and gain credibility for interview access, and it’s the only currency of our readership. Our critic is an emerging writer who is in the process of building her own reputation on the strength of her writing; a strike against her from a director might jeopardize her career. To be clear: we have no idea which people he contacted, or how many. He could have sent this to personal friends only — or he could have sent this to every publicist he knows.

We realised we couldn’t stay silent, because that’s exactly what he was trying to do: get us to silence our writer, and when that didn’t work, to silence us. And in the process of silencing us, silence the people he was contacting: he wanted them to keep the email to themselves. This director went out of his way to find and contact people who followed the writer, The Seventh Row, and our Editor-in-Chief on Twitter. Yet only one colleague forwarded the email provided above to us to alert us to what happened, adding sarcastically, “I’m sure this has nothing to do with the fact that you and the writer are women”.

We don’t hold any resentment towards the people who did not forward this director’s email to us. Rather, we see this lack of action as symptomatic of an industry still reluctant to take women seriously. For us to remain silent at this point would be condoning this unacceptable status quo of sexism in the film journalism industry.

Throughout, this director’s actions and behaviour suggest that he never meant to create a thoughtful conversation; instead, he attempted to shut down criticism. His emails are polite, but their content doesn’t withstand scrutiny. He complains of “many factual errors” but never hints at what they are; states that our critic “distorted” his film for personal reasons, though not what those reasons could be; and never indicates what specific aspects of the film he wants to “have a discussion” with us about. In his initial email, he seemed to be asking us to turn around and call out our own writer. When that didn’t have immediate effects, he turned to third parties and tried to discredit us to them. Perhaps most tellingly of all, he argued that having several women like a work is enough to discredit other women who find it misogynistic. He never reached out to the critic herself, never identified specific inaccuracies he took issue with, and never made a good faith effort to engage with our critic’s strong concerns about his film.

We do not know how many people this man managed to convince, but whether they agree with the review or not isn’t the point. Film criticism is the domain of argumentation and discussion; none of us want to see it turned into bitter and petty wars between opposing clans. That women are so often the first victims of those who thrive on division and antagonism should be surprising to no one. We hope that this piece can help assess just how much progress is still needed if we want film criticism to welcome rather than diminish diverse voices. On a more hopeful note, if you’re a writer who has been subjected to similar behaviour, this article is here to let you know that you are no longer alone.

Sincerely,

Alex Heeney (Editor-in-Chief) and Mary Angela Rowe (Editor at Large)