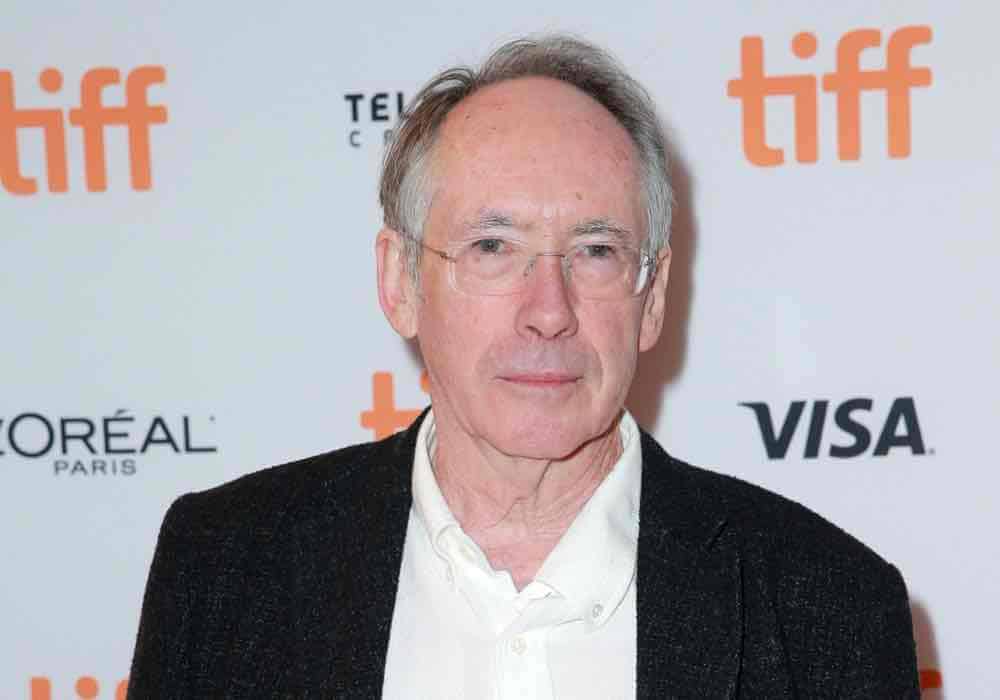

Novelist and screenwriter Ian McEwan discusses the challenges and rewards of adapting his On Chesil Beach, the importance of music to his storytelling, and why he prefers to work with directors who come from the theatre. Read the rest of our On Chesil Beach Special Issue here.

British novelist and screenwriter Ian McEwan had two films premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival — On Chesil Beach and The Children Act — both written by him and based on his books. On Chesil Beach, directed by first-time filmmaker and longtime theatre director Dominic Cooke, is about a newly married couple struggling to make their way through their wedding night. He’s working class; she’s posh; and many things divide them aside from their sexual inexperience, despite their deep love for each other. Directed by Richard Eyre, The Children Act portrays a high court justice who starts to act unethically when her personal life blows up just before a big case.

At the festival, I talked to McEwan about the challenges and rewards of adapting On Chesil Beach, the importance of music to his storytelling, and why he prefers to work with directors who come from the theatre.

Listen to our podcast on On Chesil Beach and Normal People

Seventh Row (7R): How did you get involved with adapting your own books?

Ian McEwan (IM): It’s just really by chance. It’s sort of the London bus factor, that they should come along at the same time. I worked on the adaptation of On Chesil Beach with Sam Mendes five or six years ago. He went off to make a Bond movie, I just moved onto other things. Then, it was revived through the producer and my agent. Very quickly, it sort of got on the road. Whereas The Children Act, I very much wanted to work with Richard Eyre again. We made The Plowman’s Lunch back in 1982, original script, mine. And before that, I’d done a screenplay for a television film for him in 1978.

Screenplays, writing for television and film, have been a kind of subroutine of my writing life for years. Right from the beginning, I’ve done it. I’ve worked with John Schlesinger. I’ve worked with Bertolucci, Mike Newell. I’ve written a screenplay for Hollywood called The Good Son. I’ve also been executive producer on other adaptations of mine, which other writers have done. So it’s always been there as part of my professional life.

But it is curious because not only do we have the two movies here, having their world premieres, but on the 24th of this month, Benedict Cumberbatch stars in an earlier novel of mine called The Child in Time, from 1987.

7R: How do you think about the adaptation process? What do you see as the rewards and challenges of adapting your own work?

IM: The rewards are to go back into the material and sort of meditate within it, to set yourself free in it. It’s to try to find equivalents to those things that fiction can do that cinema can’t, which is to sort of give interior states of mind, flow of consciousness, or authorial or narrative summary. There’s little essays that can fall just between a line of dialogue and the next line.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘It’s to try to find equivalents to those things that fiction can do that cinema can’t.’ – Ian McEwan” quote=”‘It’s to try to find equivalents to those things that fiction can do that cinema can’t.’ – Ian McEwan”]

For example, the scenes like the record shop scene with the little girl Chloe coming in [in On Chesil Beach]…there are instances of that all the way through, of trying to find dramatic scenes that will illustrate states of mind, that are not in the novel, or just summarizing novel. The difficulties are exactly the same as the pleasures: it’s finding those.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘There’s a strong relationship between the short novel or novella and the screenplay.’ -McEwan” quote=”‘There’s a strong relationship between the short novel or novella and the screenplay.’ -McEwan”]

I’ve always thought there’s a strong relationship between the short novel or novella and the screenplay. Screenplays are about 20,000 words. If you end up on page 100, and you’ve got to establish situations very rapidly, characters too, you’ve got room maybe for one subplot but not many more.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Novel writing is a fairly isolated, insulating business. Filmmaking is distinctly collaborative.’ -McEwan” quote=”‘Novel writing is a fairly isolated, insulating business. Filmmaking is distinctly collaborative.'”]

External to all that are the pleasures of collaboration. Novel writing is a fairly isolated, insulating business. Filmmaking is distinctly collaborative. You take a kind of demotion by convention, which is obviously being challenged in television now. But, by convention, it’s a director’s medium, not a writer’s medium — in which case, you better find good friends to work with.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘By convention, it’s a director’s medium, not a writer’s medium—you better find good friends to work with.'” quote=”‘By convention, it’s a director’s medium, not a writer’s medium—you better find good friends to work with.'”]

I think the writer’s situation in movies is always quite tenuous. For that reason, it helps, and it helped in these two movies, to work with directors whose formative years, whose whole way of approaching, has been shaped by the theatre, not by movies. So working with writers, or trying to find ways to get onto the screen what a writer has written, is much more the instinct of a theatre director.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Work with directors whose whole way of approaching has been shaped by the theatre, not by movies.’ -Ian McEwan” quote=”‘Work with directors whose whole way of approaching has been shaped by the theatre, not by movies.'”]

Classically, in the old Hollywood style at least, a writer was a kind of secretary to the imagination of the director, which is something I don’t think I could tolerate.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘In the old Hollywood style, a writer was a kind of secretary to the imagination of the director.’ -McEwan” quote=”‘In the old Hollywood style, a writer was a kind of secretary to the imagination of the director.’ -McEwan”]

7R: You mentioned that one of the limitations of cinema is in being able to represent thought patterns on screen. How do you think about translating those from the page to the screen?

IM: It’s a matter of finding a dramatic exchange. There are other ways, of course. Voiceover is one way of doing it, and we certainly toyed — in fact, I wrote all the voiceovers for On Chesil Beach. We didn’t need them in the end.

But writers rather like their own prose from their novels. If they can graft them onto a movie, we were happy with that. But you hope to get to a point where a voiceover is not actually necessary. You’re very dependent on the actors you get, and to somehow act their thoughts for you. But you still need those scenes that aren’t necessarily in the novel that will do the illustration for you.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Writers rather like their own prose from their novel—if they can graft them onto a movie.’ -McEwan” quote=”‘Writers rather like their own prose from their novels—if they can graft them onto a movie.’ -McEwan”]

Finally, you run up against a wall. There is a reality here, and we shouldn’t avoid it. The novel is probably the better form for illustrating intimacy and consciousness and conscious states. Unless you’re going to do voiceover all the way through, it’s the visual that you’re going to be relying on.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘The novel is probably the better form for illustrating intimacy and consciousness.’ – Ian McEwan” quote=”‘The novel is probably the better form for illustrating intimacy and consciousness.’ – Ian McEwan”]

7R: One of the challenges in adapting On Chesil Beach must be figuring out what to reveal about whether Florence has been sexually abused by her father.

IM: Yes, it is a strong element. The problem, in both the writing of the novel and in making the movie, was to balance this out to the right dimensions. In the successive drafts of the novel, I made it less and less obvious. In successive drafts, amazingly enough, I didn’t seem to learn from experience, successive drafts of the screenplay, the same process happened.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘In the successive drafts of the novel, I made it less and less obvious.’ – Ian McEwan” quote=”‘In the successive drafts of the novel, I made it less and less obvious.’ – Ian McEwan”]

Yes, it’s one element in Florence’s life, but we didn’t want it be the deterministic, total, defining factor of her existence. So many other things were in play: class, history, Englishness— a whole range of other things — and also character. I mean, let’s not forgot, we come into the world with whatever our parents might give us, but with a character that’s beyond the reach and influence of anyone else. Anyone who’s parenting more than one child knows this. So it was important for us to get this.

Actually, it went on even in post-production. Dominic was by then restless to find the sort of narrative curve for what’s revealed. But yes, it’s very much an element. It’s about four or five lines in the novel. Some people see it; some don’t. But it’s definitely there.

7R: Music plays a big part in the film of On Chesil Beach, and in many of your books. How do you think about music when you’re writing for a novel where obviously you can’t hear it?

IM: The music is so important. Classic musical, her world, rock and roll, his: the two don’t quite meet. She doesn’t quite get Chuck Berry and [her description of it as] “very bouncy and merry” becomes a very important plot link. But the music, that Rachmaninov for Two Pianos, mostly known as an orchestral piece, actually, um, that is the trigger for her, which the page turning into Wigmore Hall triggers her memory of the event that happens on the boat — something has happened between her and her father, to trigger her distress.

[clickToTweet tweet=”;The music is so important. Classic musical, her world, rock and roll, his: the two don’t quite meet.'” quote=”The music is so important. Classic musical, her world, rock and roll, his: the two don’t quite meet.”]

Here is actually where cinema really leaps ahead, because you can refer to “Roll Over Beethoven”, or whatever it is, or the Mozart D Major Quintet. In the movie, you can play it.

One of the loveliest things in the rushes, I’ve preserved it, is Saoirse playing the violin. Crouching behind her is a finger double — a young woman who’s a professional violin player. And she is hiding behind her. She’s curled her left hand around the fret of the violin and her fingers. So you see what looks like Saoirse’s fingers playing. Saoirse’s doing the bowing. Learning the bowing is hard enough. You’re seeing these fingers flying over in the Beethoven Razumovsky quartet, and all that’s delightful and fun, too, for me.

I think, you know, 95% of people coming to this movie never really seriously listened to that string quintet. They will have got used to that rising cello by the time they leave the cinema.

This interview was originally published on October 2, 2017.

Read the rest of our Special Issue on On Chesil Beach here.

At Seventh Row, we regularly analyse how a film works as an adaptation of a novel. We looked at why High-Rise was a very stupid adaptation and how Mockingjay Part 1 lost too many of the nuances of the book. We looked at how Brooklyn and Gone Girl worked as excellent adaptations. And we’ve talked to writer-director Joachim Trier about making film more novelistic.