Director Robin Campillo and actors Nahuel Pérez Biscayart and Arnaud Valois discuss the making of 120 BPM (Beats Per Minute), the importance of Act Up, and coming out of the AIDS closet.

When Robin Campillo’s 120 BPM (Beats Per Minute) premiered in Cannes a few months ago, it was incontestably one of the strongest and most powerful titles of the festival. Released in France in August, the film has been a popular success at the box-office, and has continued to garner strong reviews at TIFF in September. BPM follows the young and handsome Nathan (Arnaud Valois) as he joins the Parisian branch of Act Up (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). Set in the early 1990s, in the midst of the AIDS crisis, the film shows the early days of the advocacy group as it relentlessly works to limit the spread of HIV/AIDS and to get government officials and laboratories to help with treatment.

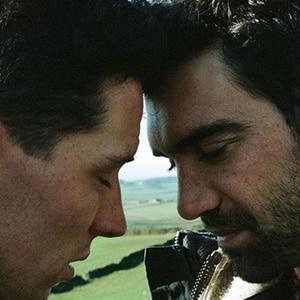

Structured around the meetings and protests of the organisation, 120 BPM follows the relationship that quickly forms between Nathan (Arnaud Valois) and Sean (Nahuel Pérez Biscayart), another member of the organisation. The film glides between their intimate romance, the meetings of the organisation, and the sex lives of all the characters with a daring and exhilarating lack of concern for genre boundaries — politics, love, and pleasure all casually meld into one.

As 120 BPM is set to represent France at the Oscars, The Seventh Row interviewed the director alongside the film’s two leads, back in Toronto.

Seventh Row (7R): Why did you want to make 120 BPM and why now?

Robin Campillo: Well, to put it simply, there have been two big stories in my life: the AIDS crisis and the cinema. It required an infinite amount of time for these two things to synchronise. In the last seven or eight years, I’ve realised that what I wanted to do was what had always been right in front of me: my time in Act Up.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘There have been two big stories in my life: the AIDS crisis and the cinema.’ – Robin Campillo” quote=”‘There have been two big stories in my life: the AIDS crisis and the cinema.’ – Robin Campillo”]

What I wanted to tell about this epidemic was this moment. I didn’t want to tell about the moments before, when, at the beginning of the epidemic, we were just good old gays dying one after the other — just victims of that illness. I wanted to tell about the moment when we became mean gays who decided to be more aggressive and to change the perception of that illness without looking like victims. When we decided to take back the power politically, to reinvent ourselves, to produce something to change this order of things that was crushing us.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘We became mean gays…to change the perception of that illness without looking like victims.'” quote=”‘We became mean gays…to change the perception of that illness without looking like victims.'”]

Ever since I realized that I was gay — I was about 4 or 6 years old — I was proud of it. Almost jealous of my secret, even. I loved the clandestinity of it. When you’re black, usually the rest of the family is black, too; but when you’re gay, it’s very rare that other people in your family are gay, too.

So you have a secret that you keep from your parents, from your brothers and sisters, etc… I always thought that this secret was an asset and a blessing. Something fantastic. I could see the same sort of thing among my other friends who were maybe gay or lesbians, and I found that extremely interesting. I think that, at the time, I was telling myself that I was a bit like Jean Cocteau or Oscar Wilde: a dandy. Homosexuality as dandyism. It was great.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘When the epidemic arrived I realised the dandy who lives clandestinely was unbearable and untenable'” quote=”‘When the epidemic arrived I realised the dandy who lives clandestinely was unbearable and untenable'”]

When the epidemic arrived, I realised that this image of the dandy who lives clandestinely was unbearable and untenable. Because suddenly, the invisibility of homosexuality was a factor in the large number of people being contaminated. All of a sudden, this posture — being alone in your corner — was too easy for the bourgeois order. It had to be destroyed.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Being alone in your corner was too easy for the bourgeois order. It had to be destroyed.’ -Campillo ” quote=”‘Being alone in your corner was too easy for the bourgeois order. It had to be destroyed.’ -Campillo “]

7R: You say it was important not to be a victim. Although these characters in 120 BPM go through horrible things, they never feel sorry for themselves. How did you manage to avoid pathos?

Robin Campillo: It was just how we felt within Act Up. It’s was a peculiar situation: we were accusing the public authorities and the laboratories of very specific things, and yet at the same time, we never blamed them for the fact that people were getting ill and died. You see? On the one hand, there was the order of the political — the labs and the politicians failing to truly recognise the illness. And on the other hand, there was the order of the illness, which no one could do anything about. Even if there was treatment, we knew deep inside that searchers could not find a cure just like that. We were angry at the labs because we didn’t have access to treatment fast enough, but we knew that it was a very complex virus. We knew that attacking a retrovirus is very difficult.

One thing to keep in mind, as well, is that when someone fell ill, this person was always a bit weary of dragging the others down with them when he died. For the other HIV positive people, it was always difficult to see someone pass away. It reminded them that they might die, too. So there was a kind of, I wouldn’t say modesty, but a pragmatism in facing this. Also, because the people who were dying were so young, it felt very unfair and extremely violent. Yet at the same time, us being young meant we could overcome things more easily. We still had a future after those people.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘When a person fell ill, it never helped them to feel sorry for them.’ – Robin Campillo” quote=”‘When a person fell ill, it never helped them to feel sorry for them.’ – Robin Campillo”]

We never felt sorry for ourselves because when a person fell ill, it never helped them to feel sorry for them. I remember that when I entered hospital rooms — which happened quite often — I would cut off my emotions. There was this mechanism in my brain. I had a sort of “poker face” when I came face to face with the ill person, because they could see in your eyes the state that they were in — how ill they were. They might have thought it didn’t show, but it did; even from one month to the next, you could see the progression of the disease. We pretended that nothing was happening. It was a mirror game where no one would reflect and send the pain back to the others.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘We pretended nothing was happening…a mirror game: no one would reflect and send the pain back to others.'” quote=”‘We pretended nothing was happening…a mirror game: no one would reflect and send the pain back to others.'”]

I was thinking of this Jacques Rivette quote when making BPM: “If there are too many tears on screen, there are no more tears in the room.” In the film, when Sean dies, only two people cry. The others don’t really know what to do with the body. That’s the reality. In reality, people do not cry like that, especially when the body is still here.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Seeing someone die like this puts you in a much more abysmal, vertiginous state than that.’ – Campillo” quote=”‘Seeing someone die like this puts you in a much more abysmal, vertiginous state than that.'”]

If, when someone dies, we just needed to have a good cry and everything would be fine, we would know it by now! Seeing someone die like this puts you in a much more abysmal, vertiginous state than that. If I make movies, it’s to make others realise these emotions that are actually quite complex. This is what moves the viewer, because they recognise something that they might live, I think.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘If I make movies, it’s to make others realise these emotions that are actually quite complex.'” quote=”‘If I make movies, it’s to make others realise these emotions that are actually quite complex.'”]

7R: You said you realised that being secretive in your homosexuality didn’t work anymore during the AIDS crisis. Is that where the character of Nathan comes from?

Robin Campillo: A little bit, because the AIDS crisis rebuilt the closet around gays. Meaning, the shame of being ill replaced the shame of being gay. In Paris, the Gay Pride was huge until 1982. Then, the numbers went down with the AIDS crisis. Then, they got back up with Act Up and other groups. The pride came back.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘The AIDS crisis rebuilt the closet around gays. The shame of being ill replaced the shame of being gay.'” quote=”‘The AIDS crisis rebuilt the closet around gays. The shame of being ill replaced the shame of being gay.'”]

The character of Nathan resembles me in what he says of his past. When he confesses about his history, I could have said exactly the same thing. When the epidemic started, I suddenly cut myself off from all forms of sentimentalism and community, to protect myself. I wanted to protect myself completely, meaning no sexual intercourse with men, no longer hanging out with other gays, no longer reading any newspapers with the words ‘AIDS’ on them. It was a sort of denial. It wasn’t the kind of denial of those who said ‘fuck it’ and had unprotected sex even though it was dangerous, but it was still a sort of denial.

When Nathan says that in the film, we can see clearly that he hasn’t pushed himself to engage with the community very much. It’s someone who is discovering the community and who, at the same time, is creating an intimacy with Sean within this community. But I’ve always felt that he falls in love with Sean the same way he falls in love with the group, in a way. You can feel that he hasn’t completely acknowledged or been in sync with the events of the beginning of the AIDS crisis, especially in the way he’s dealt with the death of his first boyfriend.

Joining Act Up is a sort of second chance for him, where he can change the order of things a little bit and change his attitude from the way he acted at the beginning of the crisis. It’s important to remember that Act Up was a revolution towards the outside world, asking people on the outside to care about us and help us, but it was also a revolution for ourselves too. A way to reinvent ourselves, for ourselves.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Act Up was a revolution towards the outside world, but it was also a revolution for ourselves.'” quote=”‘Act Up was a revolution towards the outside world, but it was also a revolution for ourselves.'”]

7R: You talk about the collective and the personal. This rings true with the way the film itself is constructed: there are lots of characters, who work together as a collective, but each feels like a fully-fledged person, too. How was it for you, Arnaud and Nahuel, working both just the two of you together, and in a group with the other actors?

Arnaud Valois: It was a little different for me than for Nahuel, because the character of Nathan arrives in the association as it already exists. He discovers them just like that, from the outside in. That’s why his integration really happens progressively as the film goes on. Because we shot in chronological order, I just had to watch and listen to the other actors, and the relationship between Nathan and Sean thus built itself quite naturally. It was quite a natural process.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Because we shot in chronological order, I just had to watch and listen to the other actors.'” quote=”‘Because we shot in chronological order, I just had to watch and listen to the other actors.'”]

Nahuel Pérez Biscayart: From the first rehearsals, I was completely blown away by the performances from the other actors. I felt like a total impostor. I thought I wouldn’t be able to do this film, because everything else was so perfect. Everyone had such raw, vivid talent. Something happened in the first three rehearsals where the idea I had of myself turned out to be pure fiction. It was brutal. I felt like a little child. But that’s the best thing that can happen when making a film. After that, there’s work that we can do on our own, but when you’re surrounded by people who put you to the test a little, and who give you a lot of material to work with and bounce back, the work is basically done.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘When you’re surrounded by people who give you a lot of material to bounce back, the work is basically done.'” quote=”‘When you’re surrounded by people who give you a lot of material to bounce back, the work is basically done.'”]

Arnaud Valois: That’s the magic of the casting, which itself took a long time to be put together. But after that, in three days of rehearsal, we were already a group. We would go for drinks together, we’d hang out before and after the shoot…

Nahuel Pérez Biscayart: There was a very strong collective fear of messing up, too. A fear that put us in a state of overexcitement during the rehearsals.

Robin Campillo: It was really quite joyful. When young directors ask me for tips, I always tell them: think about the casting. And yet, you can say it a hundred times, you still see people who do not take the time to perfect the casting. But it’s so important.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘When young directors ask me for tips, I always tell them: think about the casting.’ – Campillo” quote=”‘When young directors ask me for tips, I always tell them: think about the casting.’ – Campillo”]

Because if the character you were thinking of is close to the actor and the actor does something with it, then it can be more or less successful on set, but everything is possible. Whereas if it isn’t the right actor, nothing is possible. It will never work.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘The actor and I won’t always agree on everything, but we must at least agree on the basics…on a visceral level.'” quote=”‘The actor and I won’t always agree on everything, but we must at least agree on the basics…on a visceral level.'”]

You can’t model an actor that way. It would be like forcing a lefty to be right-handed. Everything depends on that. The actor and I won’t always agree on everything, but we must at least agree on the basics. We must agree on a visceral level.

Keep reading about great queer cinema like 120 BPM…

Call Me by Your Name

Read Call Me by Your Name: A Special Issue, a collection of essays through which you can relive Luca Guadagnino’s swoon-worthy summer tale.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Read our ebook Portraits of resistance: The cinema of Céline Sciamma, the first book ever written about Sciamma.

God’s Own Country

Read God’s Own Country: A Special Issue, the ultimate ebook companion to this gorgeous love story.