The Night of all Nights director Yasemin Samdereli worked through doubts about her own marriage by making a documentary about long-term relationships and what makes them last.

The magic ingredient for maintaining a lasting, loving romantic relationship is still a mystery. What keeps people together? Why do so many marriages and partnerships end in separation? German director Yasemin Samdereli’s first feature length documentary, The Night of all Nights, aims to get to the root of these seemingly unanswerable questions.

Samdereli follows four international couples who have been together for more than 50 years. German couple Hildegard and Heinz — Samdereli’s grandparents — got married in 1960; Shigeko and Isao, a Japanese couple, have been married since 1951; Kamala and Nagarajayya, from India, married in 1961; Bill and Norman, an American gay couple, first met in 1962. Within formal interviews, each share intimate stories about their relationship and their struggles to maintain a personal connection.

Samdereli cites two major inspirations for the project: first, her grandparents. She shares, “They were so young when they got married. They had no sexual education at all, so they didn’t know anything about the physical side [of marriage]. That was one aspect of my curiosity.” The other aspect was that Samdereli had recently been married herself. “I had just gotten married, and it wasn’t going well. I was unhappy and thinking about divorce already.” In her period of doubt, she investigated different couples who had been married for a long time. “I wanted to talk to people who had been married for 50 years and try to see what it is that keeps people together. I wanted to examine this very complex thing called love.”

Interested in interviews with doc filmmakers? Pick up our Documentary Masters eBook now, and read what some of the best in the business have to say about their craft.

She co-wrote the documentary with her sister Nesrin, whom she typically collaborates with on fiction features. But most of the work developing the story was done in the editing room, after shooting was complete. “For a documentary, you write while you edit it, because you have so many options,” she explains. “You can start from the end, [or] you can focus on one specific aspect. What were the [couple’s] challenges? And where do they stand in life right now?”

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘For a documentary, you write while you edit it, because you have so many options.'” quote=”‘For a documentary, you write while you edit it, because you have so many options.'”]

To find her subjects, besides her grandparents, Samdereli relied on a network of international producers, documentary filmmakers, and journalists who could research other married couples. Each researcher brought Samdereli “little summaries of different couples’ relationships: how long they’ve lived together, how old they are, and how they met.” Then, Samdereli would meet with each couple to get to know them. “In this meeting, you see if you fall in love with the subjects. Most of them were really beautiful human beings and had a great sense of humour. They could be themselves,” she explained.

Once they confirmed the subjects, Samdereli travelled, met with each couple for “eight to ten days, and lived with them in their everyday life.” She describes filming the subjects in their environments as “being in the shadows and following them.” Sometimes, she would sit them down for a more formal interview session to go further into the history of the relationship. Each couple got used to Samdereli and came to feel more and more comfortable with being filmed. To create intimacy and ease with her subjects, it was important for them to “not feel pressure.” When “you talk to people and ask them personal things, [you have to] give them as much personal space as possible.”

The biggest challenge for Samdereli was conducting interviews when she didn’t speak Japanese or Hindi. She wanted to talk to the subjects directly, without a translator when discussing sensitive topics. “We had a translator sitting next to me who would translate what they were saying into my language.” Samdereli continues, “but we had those translators outside so they would not interfere with the sound of the recordings. The translator would translate into my ear [via headphones] while I was filming.” This would allow the conversation to be “normal and very natural.”

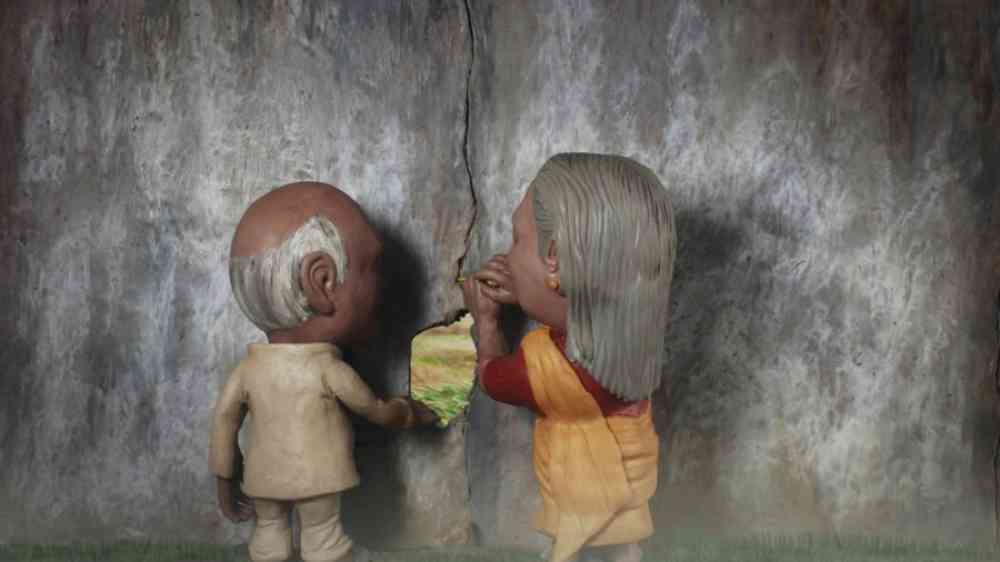

The film uses claymation vignettes to show each couple’s affection for one another, adding a touch of whimsy, humour, and lightness to the documentary. Samdereli herself sees the animation as “a special layer of poetic realism. They [reflect] a visual aspect of that couple.” She explained further, using the example of the American gay couple: “[People stated that,] when same sex marriage becomes legal, hell should freeze over. I loved that image.” She demonstrates the gay couple freezing hell over in a claymation sequence. “They got married. They were the couple that made hell freeze over because they managed to beat the system.”

Samdereli doesn’t ignore the struggles the four couples have faced in their marriages. Isao, the Japanese woman, was forced into an arranged marriage to Shigeko. She initially struggled with the relationship, even running away back to her parents’ house. “She did not fall in love with the man when they first married,” Samdereli explains. But after they had their first child together, things changed. “[Isao] fell in love with the father. I think most people start as a loving couple, then when you have children, you suddenly have three or four people in a relationship and you struggle. With them, it was the other way around. She saw how lovely he was as a father. That made her fall in love with him.”

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘You’re not always happy. It’s not about butterflies in your stomach and living happily ever after.'” quote=”‘You’re not always happy. It’s not about butterflies in your stomach and living happily ever after.'”]

I asked Samdereli what she thought younger audiences might learn from these couples. What wisdom about love could they ultimately share? “You’re not always happy. It’s not about butterflies in your stomach and living happily ever after. Actually, it’s alright if it’s not great. It’s alright to be depressed.” What someone should remember is “there’s a difference between love and being in love. It is about embracing being with each other.”

45 Years and Meditation Park both explore women as they start to reconsider their place in their long-term relationship. While both of those protagonists struggle to assess how happy they are in their marriage, After Love and Things to Come observe characters after the end of an unhappy relationship, coming to terms with life in the wake of divorce. In a totally opposite way, The Party observes the breakdown of a marriage in real time, through the lens of black comedy. But for a more comforting look at long term relationships, the central couple in Paterson find happiness in their mundane daily routine, long after that initial rush of infatuation is gone.