Kusama: Infinity and The Price of Everything, two art docs that premiered at Sundance this year, investigate the prejudices and elitism of the art world.

Art documentaries tend to have a self-selecting audience: if you like art, and are interested in how it’s made, you see art documentaries. If you know the artist, you see the documentary; if you don’t, you might consider using it as an entrée. I’m not sure I’d have been interested in a film like 2016 Sundance premiere, Sky Ladder — a thoughtful if not ground-breaking look at the creation of Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s gunpowder works — had I not seen his exhibit at the Guggenheim. Occasionally, a film like Wiseman’s National Gallery (2014) will make you think about how to look at art and give you new insights into what paintings do. Gerhard Richter – Painting (2011) is the rare film to find dramatic tension in watching an artist think: will he add more paint or take apart what he’s already done? It’s a fascinating look into the artistic process.

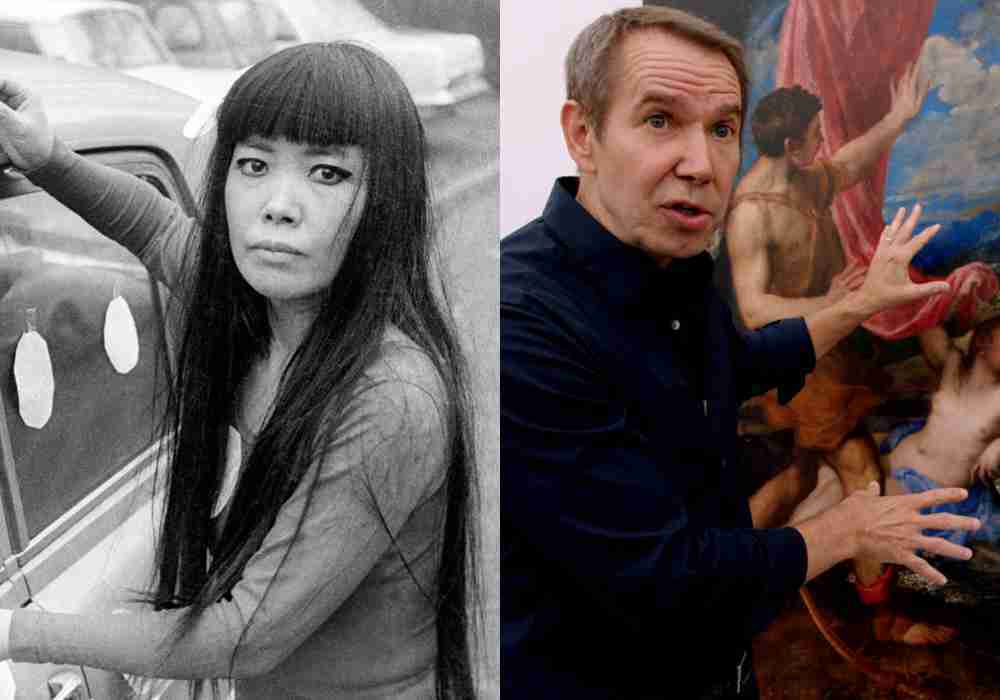

This year, Sundance featured two art documentaries — Kusama: Infinity and The Price of Everything — both of which focused more on the art world than the artist’s work. Heather Lenz’s Kusama: Infinity serves as a primer on the life and works of Yayoi Kusama, but is primarily interested in Kusama’s effect on the art world, and its discrimination against her. Meanwhile, The Price of Everything focuses entirely on how art prices are determined, often arbitrarily, and how these prices affect the art world and the public’s access to great art.

Lenz seems most interested in offering an art history corrective. Although the film offers key biographical details, and some insight into Kusama’s process, its focus is on how Kusama came to prominence: slowly, while her colleagues, who had actually copied her, got all the attention for being first. Nobody wanted to show Kusama’s art, and nobody wanted to buy it. Her approach to installation art — creating a room for people to enter and experience — was pioneering. But Andy Warhol was the one who got all the plaudits for his ingenuity, when in fact he was copying and repurposing Kusama’s ideas after attending her exhibit himself. As a woman of colour in the New York art world, and a foreigner to boot, she was practically invisible. Those that did see her work often thought she was crazy because what she was doing was so radical. But when a man like Warhol does the same thing, he’s named a visionary.

Part and parcel with this historical corrective is to turn Kusama’s story into an inspirational journey of female success. The art world may have been hostile toward Kusama, but she didn’t let that stop her from continuing to make art and find creative ways to exhibit it. When the Venice Biennale wouldn’t have her, she set up her own exhibition tent; it was public property, after all. When the galleries didn’t come knocking, she showed up on their doorstep and refused to leave until they gave her a chance.

Lunz juxtaposes Kusama as a young, plucky self-advocate with her as a now successful artist who actually lives in a psychiatric institution, making daily trips to her studio to work. When Lunz shows us Kusama’s first official exhibit at the Venice Biennale — the first Biennale exhibit for a solo female artist — we understand how hard-won this success was. It’s not just that Kusama is receiving a coveted honour — it’s one that she’d been actively shut out of in the past, at least in part because of her race and gender. Here, she gets to proudly represent her country and her gender. Now, Kusama is one of the top selling artists in the world, not to mention one of the most beloved.

Interested in interviews with doc filmmakers? Pick up our Documentary Masters ebook now, and read what some of the best in the business have to say about their craft.

I was mainly interested in seeing Kusama: Infinity because her Infinity exhibit was the hottest ticket in Toronto this year. I hadn’t even heard of Kusama before the exhibit was announced, yet online wait queues lasted hours and tickets sold fast; people are now queuing for hours each morning for a chance at the few coveted rush tickets. It was disappointing to discover that this is exactly who the film’s target audience was. It’s the kind of informative film you could see complementing an exhibit: we get access to some of her works, but the focus is only slightly on what they mean, what inspired them, or how she approaches each new work of art. It’s more about the context in which they were made: an art world that was extremely racist, sexist, and xenophobic, meaning Kusama had an uphill battle to get noticed and then recognized for her pioneering work.

While Kusama: Infinity explores why it took so long for Kusama’s art to be recognized as important and priced accordingly, Nathaniel Kahn’s The Price of Everything interrogates, more generally, how and why the financial side of the art world can be so fickle. Price often has more to do with demand than quality, and demand can be generated simply by the right person supporting a piece of art — and collectors following like sheep. In the last few decades, the price of art has increased exponentially, to the point that the art market is a place for asset management more so than art appreciation. Kahn’s film asks: is art expensive because it’s great? Is great art always expensive? Or is there little correlation between the price of an artwork and its quality? Kusama: Infinity suggests that price is more closely linked to fame and fad than quality. Now that Kusama is in fashion, for example, her art sells for millions. But there was a time when nobody would bite at all. If recognizing art as great is arbitrary, driven by other social values like misogyny and racism, then pricing art is no different.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘Is art expensive because it’s great? Is great art always expensive? Or is there little correlation between the price of an artwork and its quality?'” quote=”‘Is art expensive because it’s great? Is great art always expensive? Or is there little correlation between the price of an artwork and its quality?'”]

Kahn closely follows a Chicago art collector, a New York art auctioneer, and a still relatively obscure artist (Jeff Poons) who came up with the abstract expressionists, each of whom offer differing perspectives on what art pricing means and how it works. Early on, there’s a suggestion that great art is expensive as a measure to protect it, because people will handle it with care. Yet throughout the film, there’s a tension between whether art should be for the masses or for individuals. Perhaps because selling art is her job, the auctioneer believes that a great piece of art can change a person’s life, if they live with it. She’s unbothered by the prospect of taking artwork out of the public sphere.

But because art is worth so much, it becomes an alternative asset — a way of storing money. Kahn interviews multiple art historians who bemoan the rising prices of art because it means that museums can no longer afford to participate in auctions. Instead, these pieces become part of private collections, closed off from public view. Worse, the people who can afford to make these purchases often aren’t even art lovers. When the auctioneer is trying to make a sale to a regular customer, she comments on how unique this acquisition will be; she contrasts this with how so many Park Avenue apartments have pieces by the same artists, in the same place, as if the art were a lifestyle statement rather than something to gaze at and consider. Even the Chicago art collector, who the film follows, tends to talk about the pieces in his collection, and that he desires, from the perspective of how much they’re worth or how they’ve been deemed important. His personal feelings, about the individual pieces and the emotions they evoke for him, seem irrelevant.

The Chicago art collector is the kind of person who people initially thought overpaid for certain pieces, by millions of dollars — but he’s seen a return on his investment. When he talks about his art, it’s so often about the importance of an artwork rather than his own personal enjoyment of it. This may account for why, as a Jewish immigrant, he owns Maurizio Cattelan’s controversial sculpture of a kneeling Hitler, “Him”. Considering how much he’s invested in his collection, it’s just as fascinating to discover that, when he donates a chunk of it to the Chicago Art Institute, replacing an original painting in his apartment with a print, that he’s just as happy with the print. If a print will do, why did he spend so much time and money on procuring the originals? Was it merely a form of asset management rather than a real passion?

Through the New York auctioneer, we encounter contemporary artists with a complicated relationship to how much their paintings are worth. If, for example, they hit on a style that attracts high prices, should they keep reproducing this style and stop growing as an artist? One reason Jeff Poons remains in relative obscurity is because he keeps changing his style, meaning he’s no longer making art similar to what he was doing in the 1950s, for which he’s best known. When he sold his paintings back then, he made little profit. But the business of art auctions has driven up the prices, making other people rich. To Poons, though, to repeat old work would be to go backwards, and he pays for that choice by not seeing the fame and fortune he could otherwise achieve. Similarly, we meet emerging artists who are torn between sticking to a profitable style for practical reasons, or risking losing popularity by growing and changing as an artist.

Kahn’s answer to the question of why art is so expensive isn’t simple: he suggests that the problem lies with pricing being so illogical and wide-ranging. The very rich can profit from an art collection, but they may not enjoy it. Meanwhile, the rest of us get closer and closer to being shut out from the opportunity to even experience the great art that happens to be expensive. On the other hand, price can obfuscate what actually is great: just because a piece sells for millions, doesn’t mean it’s good so much as that it’s a fad.

Faces, Places follows photographer JR’s and legendary director Agnes Varda’s road trip across France as they create giant murals of the faces of people that they meet along the way. Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami lets us get to know the legendary musician and see her stage performances specifically for the film. I Called Him Morgan tells the story of jazz trumpeter Lee Morgan and how his wife ended up murdering him.