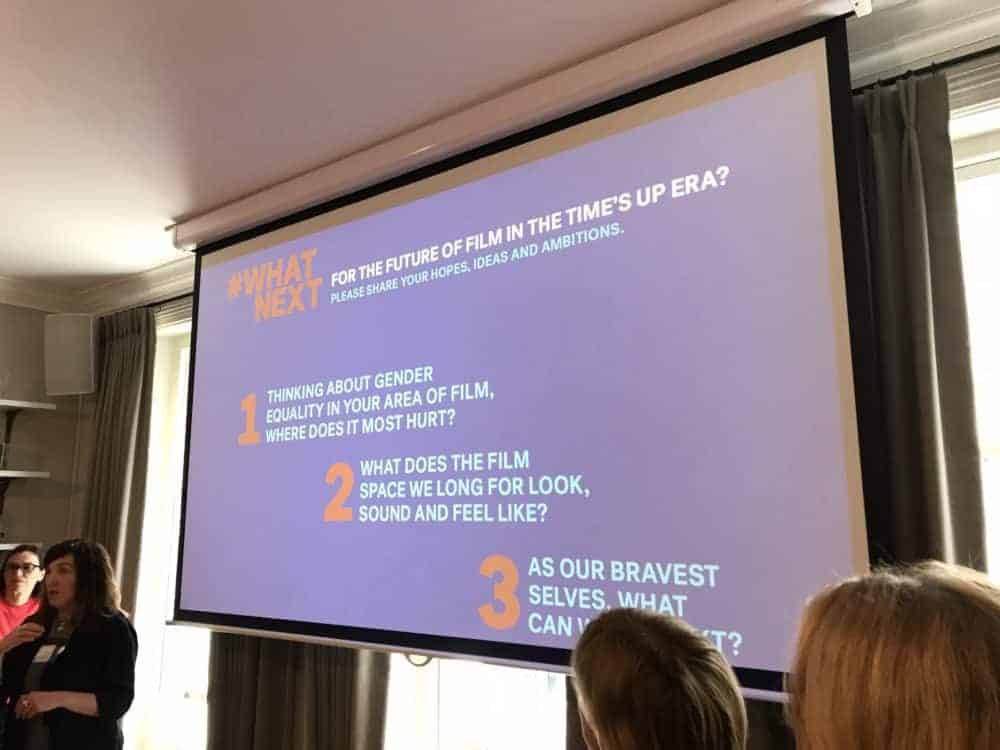

At the #WhatNext breakfast organised by Sundance London, women from all areas of the film industry discussed concrete ways in which to go beyond a general awareness of sexism, and forward into actual change.

The atmosphere last Wednesday at the #WhatNext breakfast at the Allbright, a women-only members club in London, UK, was electric but warm, calm yet urgent. It was odd and refreshing to be in one of those luxurious London townhouses where film events often take place, without finding myself stared at or talked to by some middle-aged man gracing me with his company and infinite wisdom. In fact, only two men were present that morning: one young journalist reporting on the event, and a Sundance London programmer.

Over three days in May-June, Sundance London screens a selection of some of the best films shown the previous January at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah. Many of those films are UK premieres of highly anticipated titles and this year, most of them were directed by women — 58%, an unprecedented number. Yet the festival went beyond this feat and made feminism in the film industry the theme of this year’s edition, which only makes sense in the wake of #MeToo.

Organised by Sundance London, the #WhatNext breakfast saw women from all corners of the UK film industry convene to discuss how to turn dreams of equality into reality. Several months after the #MeToo movement started, Sundance London is one of the few organisations in film to ask what the next steps towards equality might be. While some sexual predators are already planning their comebacks, and other organisations are proving as sexist as ever, the festival seems willing to go beyond this moment of general awakening, and forward into action. Perhaps even more encouraging than the initiative alone is the fact that it is lead and directed by women, deciding what needs to be done for and by themselves.

The festival is produced this year by Mia Bays, a programmer and producer whose own agency, Birds Eye View, organises events year-round to increase the visibility of films directed by women and to support women working in film. Working with Picturehouse and Sundance, she is behind this year’s focus on equality: beside the 58% female-directed programme, the festival has also planned several panels and screenings to let women talk and take control.

The #WhatNext breakfast opened with a message of enthusiasm and hope from Picturehouse’s Director of Programming Clare Binns, and a call for all women present to open up to and help each other.

Changing our own mentalities

Film critic Kate Muir, host of the event, described how despite some discouraging words in various #MeToo-themed meetings she has attended, the momentum has not faded out. She talked about the position of “supplicancy” towards men that women in the film industry often find themselves in, and how this mentality also needs to change.

Mia Bays then encouraged attendees to talk to each other even if they’d never met before — to create a system of help and exchange which would stand in sharp contrast to the system of supplicancy outlined by Muir.

As a woman who tends to be awkward around other women — my learned impulse has always been to compare myself to or even compete with other women — this mingling in a room entirely composed of women felt nothing short of radical, and more than a little intimidating.

Rather than dismissing those of us who might have a hard time reaching out to each other, this breakfast explicitly offered a safe space to try and overcome such competitive, toxic habits. Mia Bays and Clare Binns repeatedly encouraged attendees to talk to women they did not know, and up on the slide was the question: “As our bravest selves, what can we do next?” Besides acknowledging that women should help themselves and each other, rather than expect men to act, this question also crucially evoked the courage necessary for change.

Greater ambition

The event also emphasized the importance of revising our ambitions and asking for more than we’re used to. Members of the New Black Film Collective talked about the way women — and especially women of colour — can become so used to getting nothing, they sometimes end up thinking there simply isn’t anything else out there for them.

Film4 representatives echoed this sentiment when talking about the way women directors sometimes do not dare to pitch films with big budgets and larger ambitions.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘Rather than dismissing those of us who might have a hard time reaching out to each other, this breakfast explicitly offered a safe space to try and overcome such competitive, toxic habits.'” quote=”‘Rather than dismissing those of us who might have a hard time reaching out to each other, this breakfast explicitly offered a safe space to try and overcome such competitive, toxic habits.'”]

Helping each other

Film4 also addressed another theme which would come to dominate the discussion: the need for women in different corners of the film industry to help each other. In other words, what is needed is a network of allies.

Talking from experience, they explained that a film was likelier to be picked up if it did not frame itself as ‘female’ and thus reserved for a niche audience. Rather, a film directed by a woman and focused on a female character stood better chances if it was pitched as an adult story for contemporary audiences who crave this kind of content. The Film4 representatives encouraged people who are about to pitch their film to ask for help from those “who can help and explain how to pitch in a way that might get the film made.”

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘The event also emphasized the importance of revising our ambitions and asking for more than we’re used to.'” quote=”‘The event also emphasized the importance of revising our ambitions and asking for more than we’re used to.'”]

Fiona McGuire, Pathe UK production manager, talked about a shortage of filmmakers as “an opportunity to make people look in a different direction for new talent”: in the direction of women. Progressively, suggesting women over and over again should change mentalities until, one day, male colleagues might make such a suggestion themselves.

Half an hour in that morning was dedicated not to networking — a term which often implies a rather self-serving goal — but, in the words of Clare Binns, to “reaching out to people where you can make a difference for the greater good.”

Putting women filmmakers in the spotlight

Representation remains a powerful tool for helping to change mentalities and help women in the film industry. Gaylene Gould, head of programming at BFI, talked about how the BFI is working “to create spaces for contemporary, diverse voices” such as the seasons this summer dedicated to the work of Agnes Varda, Ida Lupino, and Ava DuVernay.

Clare Binns described similar effort from Picturehouse “to put women front and centre of the films that we’re buying.” Picturehouse recently left Cannes with Jury Prize winner Capernaum from Lebanese director Nadine Labaki, and Benedikt Erlingsson’s Woman at War, focused on a middle-aged woman involved in environmental activism.

On a smaller scale, but one that is just as significant, Girls on Film helps upcoming, emerging women filmmakers who haven’t made their debut feature yet and are struggling to get their short films made.

Changing the face of the industry by introducing women at every level

In the presence of women who work every day in the film industry — and who are thus all, in a sense, behind the camera — the importance of having women behind the scenes took centre stage. Julia Oh from production company Film4 emphasised the need for women in every area of the film industry in order to achieve true equality, an idea furthered by representatives of the media agency Film London.

BFI Network helps provide funding to emerging filmmakers, but also helps women in other areas of the film industry, such as producing.

Anna Smith, from the London Critics’ Circle, talked about the lack of diversity in film criticism, and the importance of editors who make the choices about who gets to write about what, and which voices are heard.

Minorities and new voices

The feminism at the #WhatNext breakfast was decidedly intersectional; questions relating to class and minorities naturally came into the conversation.

The production company Ink Factory emphasised the benefits of hiring diverse interns. Rather than simply working to develop the ideas of their bosses, interns present “an opportunity to really find out what these other voices are that we don’t see, and to try and change the face of what we think a filmmaker is supposed to look like.”

In a similar vein, Creative Access pays for young people from minority backgrounds to come down to do their internships.

Keeping the momentum going

Clare Binns closed the event with an imperative: “Let’s use Sundance London as a starting point.” Women must keep talking to each other, and helping each other. The conversation must continue.

It quite literally did at the public #WhatNext panel on Friday. Kate Muir, Lauren Dark of Film4, Eva Yates of BBC Films, and filmmaker Amy Adrion (who directed the documentary Half the Picture about sexism in Hollywood) talked about these same ideas in front of an audience.

The festival also asked three of the women filmmakers who have their films in the line-up to screen one movie that ‘made them’ — thus once again centring the female experience, the experience of cinema. Desiree Akhavan, director of The Miseducation of Cameron Post, chose to screen Seventh Row favourite Morvern Callar, while Debra Granik will present Celine Sciamma’s Girlhood, and Jennifer Fox of The Tale chose to show the documentary Tarnation. All three filmmakers will be on a panel together on Saturday to discuss their careers and filmmaking processes.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘With major events such as this year’s Sundance London taking on the topic of feminism in such a big way, focusing on women in film feels significantly less isolating than it did just a few months ago.'” quote=”‘With major events such as this year’s Sundance London taking on the topic of feminism in such a big way, focusing on women in film feels significantly less isolating than it did just a few months ago.'”]

With major events such as this year’s Sundance London taking on the topic of feminism in such a big way, focusing on women in film feels significantly less isolating than it did just a few months ago. With the concrete work of all the impressive women of the #WhatNext breakfast already in place, and many more initiatives still to come, equality feels more like a possible reality, and less like something we merely wish for. The three days of the festival promise to give a snapshot of what might one day become mainstream — a film industry giving women the space which their talent and voices deserve.