Co-directors Jennifer Baichwal, Edward Burtynsky, and Nicholas de Pencier discuss their third film collaboration, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch. This is an excerpt from the ebook The Canadian Cinema Yearbook which is available for purchase here.

The central tension in Edward Burtynsky’s photographs is that they’re gorgeous, and yet they depict the human destruction of the earth’s ecosystems. You view his photos in awe at their majesty; their beauty is what makes them so terrifying. In 2006, Burtynsky started collaborating with director Jennifer Baichwal and producer-cinematographer Nicholas de Pencier to turn his photography books into feature films. Manufactured Landscapes (2006) tackled industrial landscapes and the waste they generated. Watermark (2013) explored how humans have leveraged water resources and caused environmental destruction in the process. Like Burtynsky’s photographs, the films are impressive works of art, best seen on the big screen to capture the scale of the landscapes.

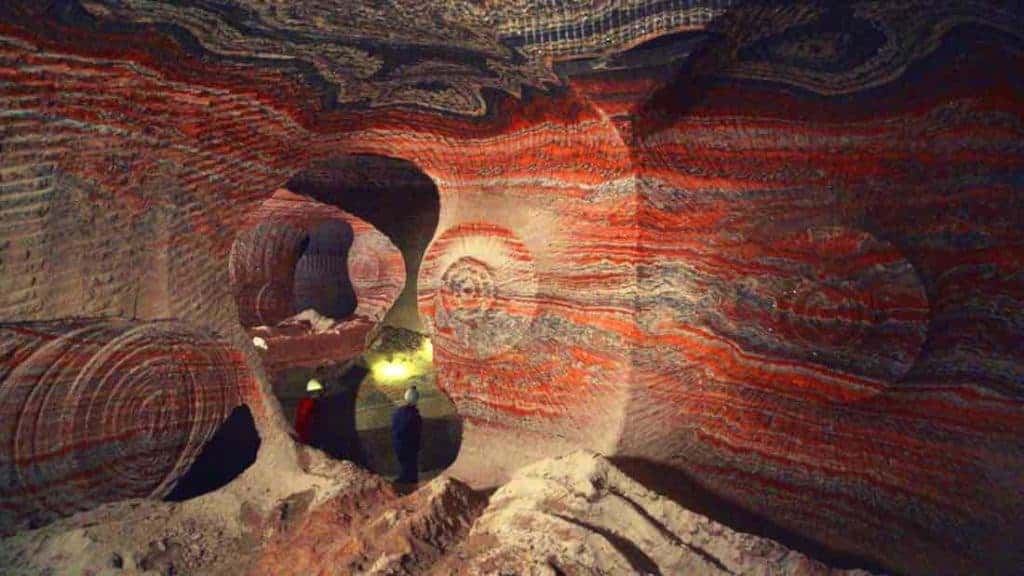

Their new film, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch, which premiered at TIFF earlier this month, is their most expansive and best collaboration. The film takes its title from the term proposed to denote the current geological age, in which human activity is the dominant influence on climate and the environment. Taking us around the world, the film gives us a glimpse of the extent of the human impact on the natural environment — from the effects of mining and industry, to animal extinction, to climate change. A carefully curated voice-over by Alicia Vikander provides important context for the images we’re seeing (something Watermark disappointingly lacked). It piques our curiosity to learn more and gives us space to contemplate the significance of the images we’re seeing.

At the Toronto International Film Festival, I spoke with the all-Canadian filmmaking team — co-directors Jennifer Baichwal, Edward Burtynsky, and Nicholas de Pencier — about their evolving collaboration, their approach to telling stories about the human impact on the environment, and what the film offers that an art exhibit or book can’t. The film’s Canadian release coincides with the opening of the exhibit of the same name, co-created by the trio, at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

7R: Anthropocene is the third film that you have done together, after Manufactured Landscapes and Watermark. How has that collaboration evolved through the years?

Jennifer Baichwal: It started with Manufactured Landscapes. I remember our friend Daniel Iron, our longtime producing partner, said, “Are you interested in looking at 120 hours of video material to make a film?” So I watched all of it with our editor. All the black and white stuff in Manufactured Landscapes is from this.

Edward Burtynsky: That must have been painful!

Jennifer Baichwal: And I made the decision we could make a film, but it could not just be with this footage. That’s what started this process. It was me directing a film about Ed, where I really wanted him to be the author more than the subject. It wasn’t a traditional bio-portrait, but more a study on how to intelligently extend the meaning of the photographs into the medium of film.

In Watermark, it was more of a co-direction. Ed had already started doing that photographic essay. We came in and decided to make a film. Nick was the cinematographer and producer.

On Anthropocene, Nick is the main cinematographer; Ed did some cinematography. We are all directors of it. I’m more the lead, the person who sits in the editing room with our editor Roland Schlimme to put the puzzle together.

Our relationship has evolved and gotten much richer and more complex, especially since we are also doing this museum exhibition which is anchored by Ed’s photographs but with film installations and augmented reality, sculptures. It’s a lens-based exploration, using whatever lens works the best to convey this subject.

Edward Burtynsky: To add a little bit to that history — that 120 hours of footage [that Jennifer received for Manufactured Landscapes] it was from Jeff Powis who wanted to make a doc about my work, but he had never made a doc before. I had some conditions for him making it like, “You can’t slow me down” and a whole bunch of other things. When he put something together, I had the right to say I liked it or didn’t like it, and it felt wrong. So when it got shopped around, and Jennifer saw it, I saw her film as well, True Meaning of Pictures. I realized that there was a greater kind of intelligence and depth, as an exploration of photography as a medium through the medium of film.

The books are there, too, but so few people actually get to see the books or read the deeper context of these images in the book. I was excited to work with the calibre of filmmaking that they brought to the table to extend the context of the images that I was making. People could understand that these were coming out of worlds that are real, with real people…

Jennifer Baichwal: And we’re all connected to them. We’re all part of them.

Edward Burtynsky: The images are kind of disembodied. You can engage in them, but you can’t get the deeper context just by the images.

7R: What did you find that you could get from the film Anthropocene that you can’t get from the photographs? How do you see it as an extension of your work, and how do you see it as an opportunity to show something additional that won’t necessarily appear in the exhibit?

Nicholas de Pencier: One of the best compliments we got on Manufactured Landscapes was that it replicated the experience of seeing a work of art. Some films are very discursive, have a lot of information and a lot of exposition; when you watch them, it’s a very passive experience. You are just bombarded with facts and information. Sometimes, that can be good, like a power punch of learning. But it’s more intellectual learning.

Here, there is a lot of just witnessing and a different relationship with time than in a lot of the films where you have a dialogue. You’re allowed to come back with your own thoughts because there’s time to do it. I think that’s what can happen in a transformative way in an art context. I think the films stand out because of that. There’s not a lot of that kind of filmmaking, certainly around environmental issues or social issues, that lets you have that experience. It’s unique and hopefully powerful.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘There’s not a lot of that kind of filmmaking, certainly around environmental issues or social issues, that lets you have the time to think your own thoughts.’ – Nicholas de Pencier” quote=”‘There’s not a lot of that kind of filmmaking, certainly around environmental issues or social issues, that lets you have the time to think your own thoughts.’ – Nicholas de Pencier”]

7R: One obvious thing that you can get from the film Anthropocene and not from the photographs is sound. I really liked the way you could hear these environments and the noise of the destruction of these environments. How do you think about sound and the music, that may or may not start diegetically, but a lot of it seems to be things that you captured?

Jennifer Baichwal: Even from the beginning in Manufactured Landscapes, sound is crucial. Also, expressing scale and time — how you do duration. The time-based medium can tease out meaning in a different way.

In almost all cases, our sound emerges from the soundscape of where we are. We’re very careful to record a lot of location sounds. Those industrial environments are sometimes overwhelming, and then you might notice there is some melody or rhythm that is emerging that then takes over and then subsumes back into it.

It’s really important for me, in documentary, that music never leads you emotionally. I don’t believe in that. I feel it has to come from the reality of the context. But it can certainly add another layer.

In this film, all of our composers — with the exception of Mozart and the final song which is by our friends Rheostatics — are women. Female composers make up only 4% of composers in traditional Hollywood films. 4%! It’s just pathetic. They’re so great, and it was hard to find them. It wasn’t like there is a database you can go to. We really had to search. I’m really proud of and pleased with the sound design and the composition.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘Those industrial environments are sometimes overwhelming, and then you might notice there is some melody or rhythm that is emerging that then takes over and then subsumes back into it.’ – Jennifer Baichwal ” quote=”‘Those industrial environments are sometimes overwhelming, and then you might notice there is some melody or rhythm that is emerging that then takes over and then subsumes back into it.’ – Jennifer Baichwal”]

To read the rest of the article, purchase a copy of The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook here.

[wcm_restrict]

7R: The films (Anthropocene, Watermark, Manufactured Landscapes) do try to capture Ed’s photography, but he’s not always shooting it. What does that collaboration look like?

Edward Burtynsky: We were doubling up on some technology, even sometimes using the same drone: we’d take off my stills camera, put on the RED [digital movie] camera [for the film], and fly through again. Film extends the context of the stills.

People would often say about the stills, “Why don’t you come up more forcefully and caption in such a way that reveals the wrongdoing here and points out the bad guys?” And I’m thinking, if you do that, if you caption the piece, saying this is something we shouldn’t be doing — ‘raping the land’ or whatever terminology you want to use — you’ve now locked that image into a meaning as an author that doesn’t allow for an openness to fall into that image with different thoughts.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘if you caption the piece, you’ve now locked that image into a meaning as an author that doesn’t allow for an openness to fall into that image with different thoughts.’ – Ed Burtynsky ” quote=”‘if you caption the piece, you’ve now locked that image into a meaning as an author that doesn’t allow for an openness to fall into that image with different thoughts.’ – Ed Burtynsky”]

You can say, “I’m enjoying this image because of the colour and the composition,” and tomorrow I might be thinking about the subject matter of the image. I’m allowed to move around within a floating point of meaning.

I agree with Nick’s comment that the films act in a similar way. You’re not told how to interpret this information — although I think it would be hard to interpret it in a way that isn’t emotionally charged. But it’s not saying you must see this this way. To me, that is the power. We all want to open up audiences. If you just say ‘this is bad,’ then you’ve lost a whole sector of our society. Industry and a lot of the right would say that’s naive, that environmentalism is a nice thought but not practical. This way, I think everyone can be included. It becomes an inflexion point for discussion. It could be more powerful than standing on two sides of an argument, throwing rocks at each other.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘If you just say ‘this is bad,’ then you’ve lost a whole sector of our society. This way, I think everyone can be included. It becomes an inflexion point for discussion.’ – Ed Burtynsky” quote=”‘If you just say ‘this is bad,’ then you’ve lost a whole sector of our society. This way, I think everyone can be included. It becomes an inflexion point for discussion.’ – Ed Burtynsky”]

Jennifer Baichwal: But we’ve gone farther with this one. We have categories which are all based on the research of the scientists of the Anthropocene Working Group. They were the inspiration for the film. Their research of what human impact looks like on the Earth is what drove the film, its structure, where we went, and where we filmed. Terraformed and anthroturbation and technofossils and climate change and extinction — these categories informed us.

And narration. We haven’t used narration before — nly once in The Holier It Gets, a film Nick and I made many years ago, which was a personal film so it had a reason for a narration. We struggled with it a bit, but in opening up consciousness, that is a step to say, ‘what hard things can we do? What real decisions can we make towards change?’ Understanding that humans are this singular dominant force on all the systems of the planet — period — is a big revelation. It’s quite momentous to think of what we have done in this totally complex place we call Earth. If we can change it that much for our own benefit, then we also have the capacity to change it in a way that is beneficial to all life on Earth.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘Humans are a singular dominant force on all the systems of the planet. If we can change it that much for our own benefit, then we also have the capacity to change it in a way that is beneficial to all life on Earth.’ -Jennifer Baichwal” quote=”‘Humans are a singular dominant force on all the systems of the planet. If we can change it that much for our own benefit, then we also have the capacity to change it in a way that is beneficial to all life on Earth.’ -Jennifer Baichwal”]

7R: I thought the voiceover was really effective and walks that really difficult line where it helps give context to what is the anthropocene and what is going on in the film, but never feels preachy. How did you approach that?

Nicholas de Pencier: Because the film was involving some of the science and the ideas of the scientists of the Anthropocene Working Group — which was really interesting to us as a central organizing principle — we knew from the beginning that we wanted to have that in the film somehow. For a lot of time, we debated about how that might be done. We filmed lots of scenes with the scientists, but in the end, it became a different movie when we tried to edit those in.

The voiceover became the quickest short circuit to put a voice in your head. I’m glad that you say that it didn’t become too much, because it needed a very light touch: just enough context, just enough information to give meaning to the scene you are about to watch — or you just watched — and experience it viscerally, not just intellectually.

Jennifer Baichwal: It was really hard to condense that research into just enough information, and not to make it just one stat after another. The number of iterations would be over a hundred. There were a lot of different drafts, trying to get to what is the most essential information that opens this scene up, so you know what you need to know. And also the definitions: people don’t know what anthroturbation means, human tunnelling under the Earth. They don’t know what technofossils mean, which are human-created objects that persist in the biosphere, and there’s a lot of them. It was a tough balance. I’m glad it worked.

Edward Burtynsky: In all the films, and I think you guys would agree, the visuals are the room, and the words are the key into the room. You get into the room, but then you explore the room on your own. You are not being guided through the whole room. The visuals allows for that space to engage with the material. You have just enough words to understand what you are looking at.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘The visuals are the room, and the words are the key into the room. You get into the room, but then you explore the room on your own.’ – Ed Burtynsky” quote=”‘The visuals are the room, and the words are the key into the room. You get into the room, but then you explore the room on your own.’ – Ed Burtynsky”]

7R: There’s been a lot of technological change in film since the beginning of your collaboration. How has that helped to shoot these? I know you mentioned drones.

Jennifer Baichwal: Watermark was one of the first drones.

Edward Burtynsky: 2010, we were putting big RED cameras up on drones.

Jennifer Baichwal: Nick can detail it on the cameras.

Nicholas de Pencier: Yeah, technology keeps getting better and easier, in a way. The video camera that I travel with is the heaviest one that I’ve ever had in my whole career. Maybe it doesn’t get easier for us because we put so much emphasis on the production values. It’s important for us to not compromise at all: we want it to be a visceral, experiential moment. When you are in that place, nothing should detract from that. We are always at the vanguard of what the technology makes possible for resolution, for sound.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘We want ANTHROPOCENE to be visceral and experiential. When you are in that place, nothing should detract from that.’ – Nicholas de Pencier” quote=”‘We want ANTHROPOCENE to be visceral and experiential. When you are in that place, nothing should detract from that.’ – Nicholas de Pencier”]

Jennifer Baichwal: So it’s not lightweight, with just the three of us travelling around. There’s often a big crew, although it also collapses down. Sometimes it’s just me and Nick and the camera.

Nicholas de Pencier: When Ed is shooting stills, he will take some video, too, sometimes.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘You want people to be as overwhelmed by these environments as we were when we were in them.’ – Ed Burtynsky” quote=”‘You want people to be as overwhelmed by these environments as we were when we were in them.’ – Ed Burtynsky”]

Jennifer Baichwal: There’s a flexibility there, but we are trying to stay at the forefront of production values. You want people to be as overwhelmed by these environments as we were when we were in them.

[/wcm_restrict]