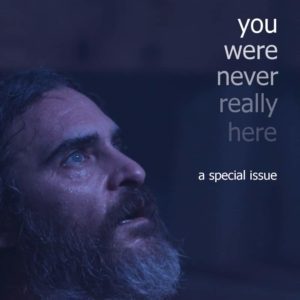

The first feature from photographer Richard Billingham is a moving yet unsentimental portrait of a life in fragments, as empathetic as it is brutal.

In his first feature film, Ray & Liz, photographer Richard Billingham demonstrates a rare eye for the details about people that, as random as they might seem, stick in the mind most. The film begins with a wordless sequence showing Ray (Patrick Romer), a man in his seventies, waking up in his bed. The room is small and completely unfurnished except for the bed and a small table. The walls are almost bare. Ray moves slowly, an unreadable expression on his face. The first thing he does after waking up is to serve himself a glass of dark beer, his hands a little shaky. He nevertheless fills up the glass to its rim, without spilling anything.

Later on in the film, Ray repeatedly drifts into memories from his earlier years, each set at different periods of his life and in different places. In these scenes from 30 years ago, populated by younger actors, it is Ray’s strange habit that allows us to recognize him. His life in this remembered past was very different from what it is now: back then, Ray (played in his younger form by Justin Salinger) was surrounded by people. The places where he lived with his wife, Liz, and his children were colourful, cluttered with objects and decorations. Throughout the years, this odd habit of filling his glass to the rim is the one thing that hasn’t changed. This seemingly innocuous quirk is at the core of Ray’s identity.

Billingham introduces us to the world of the film not through establishing shots, ‘objective’ views of architecture, or orienting pans, but through the subjective — and thus limited — memories of individual characters. These memories aren’t necessarily Ray’s, either: the camera does not stay with him during flashback sequences, and sometimes he is barely present. Though Ray & Liz centres on Ray, it may not wholly be Ray’s story — another person is sometimes doing the remembering. For example, when Ray’s younger son creeps into his parents’ room for a prank, Billingham aligns us with the child’s point of view, showing the parents’ bedroom from a lower angle as seen through the slightly ajar door. This perspective is fitting, given the film’s autobiographical slant: Ray & Liz is based on Billingham’s celebrated book Ray’s a laugh, which features photographs Billingham took of his father, Ray; his mother, Liz; and other people he knew.

Billingham’s compositions are gorgeous — some of them are close recreations of his published photographs. Yet there is more than superficial beauty at play. When the son creeps into his parents’ room, the film visually translates the emotional, cognitive way children perceive their parents: not as two individual people, but as an amorphous mass in a big bed, hidden behind a door that is usually closed. When Ray wakes up and goes to rinse his mouth, the camera stays at the child’s level, in long shot. We do not have access to Ray’s experience of this moment, but only to the way he appears to his son. Ray is mostly a silhouette, a pair of hairy legs walking slowly back to his room.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘The film visually translates the emotional, cognitive way children perceive their parents: not as two individual people, but as an amorphous mass in a big bed, hidden behind a door that is usually closed.'” quote=”‘The film visually translates the emotional, cognitive way children perceive their parents: not as two individual people, but as an amorphous mass in a big bed, hidden behind a door that is usually closed.'”]

These sequences are all the more immersive for the way they each relate intense physical sensations — things which we naturally remember best. In the first flashback, Ray’s brother, Lol, is bullied into drinking alcohol, and passes out while the young child he was supposed to take care of plays with a knife. In another, the younger son is found almost frozen to death after passing the night in a shed. In each of these memories, the physical sensations are deeply painful ones. Even while drawing us closer to the characters through these haptic flashbacks, Billingham seems determined to fight any easy, overtly romantic associations to sensation and memory. He wants us to feel and relate to this past, but never lets us fall into sentimental nostalgia.

Billingham’s understanding of the role of physical sensations in memories animates his cinematography throughout Ray & Liz. Shooting on grainy 16mm film, he lights the rooms and the subjects he shoots with degrees of shade, making their surfaces appear clear and defined. His close-ups — on faces, on objects that the kids play with, on the puzzle Liz is assembling — echo the way we tend to only remember and obsess over specific details from our past. Even Liz’s taste for intensely colourful decoration cannot consume the image or reduce it to an empty, superficially pleasing surface.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘Even while drawing us closer to the characters through these haptic flashbacks, Billingham seems determined to fight any easy, overtly romantic associations to sensation and memory.'” quote=”‘Even while drawing us closer to the characters through these haptic flashbacks, Billingham seems determined to fight any easy, overtly romantic associations to sensation and memory.'”]

Just as Billingham finds the one detail that says the most about a person, the memories that he shoots relate specific events that speak volumes about these people’s lives. Most of these memories are short stories of desire and neglect, love and disappointment, tenderness and violence; they highlight Ray’s seeming indifference, Liz’s pride, and the younger son’s desire for affection. But the details about their behaviour — Ray’s beer, Liz’s puzzles and cigarettes — unchanging across time, draw our attention to all the missing scenes in between — to all the things that we do not know, and to Ray’s own inability to chart just how he became so lonely. He cannot point to one precise moment, one specific scene that he could replay in his head; it didn’t happen in one day. All he can do is look back at some moments he remembers, and wonder if the root of his problems wasn’t perhaps already manifest there.