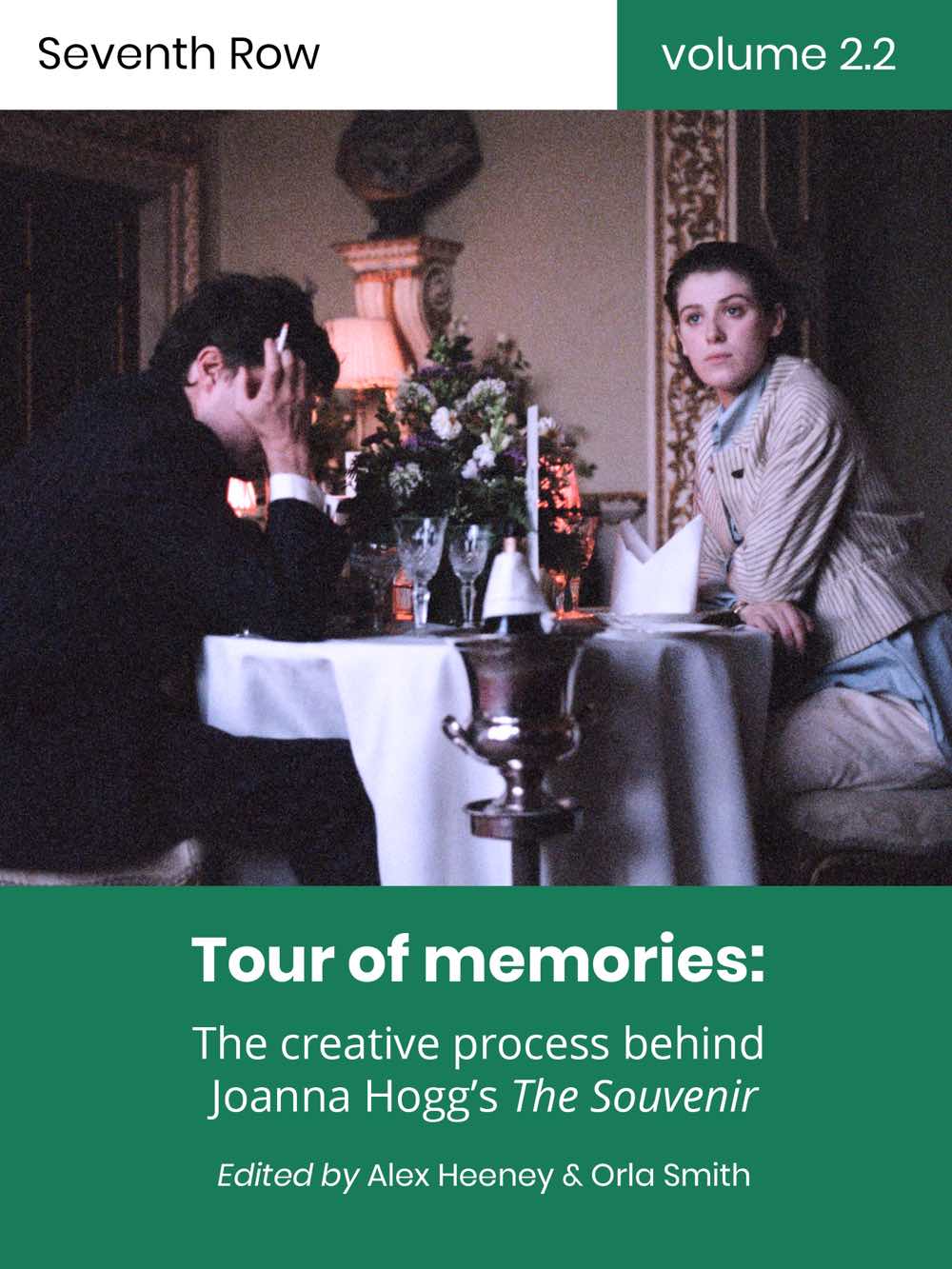

This is an excerpt from the list “Joanna Hogg’s 10 best scenes” in Seventh Row’s new book Tour of Memories: The Creative Process Behind Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir. We’ve analysed three of our favourite scenes from The Souvenir. Get the book here.

To serve as an introduction to Hogg’s cinematic style and storytelling approach in our upcoming book, Tour of Memories: The Creative Process Behind Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir, we have compiled a list of 10 of our favourite scenes from across her films. We have analyzed how these scenes function and what makes them so memorable. In this preview, we present the three scenes from The Souvenir that made the cut.

The Souvenir Scene #1: The first night Anthony stays over

The first time Anthony sleeps in Julie’s bed, a genuine intimacy blossoms between the couple, but there is no sex involved — rather, the scene involves a pile of stuffed animals. Anthony teases Julie that she is taking up too much space on the bed. “I have not got that much room,” Julie laughingly replies.

It is an endearing moment, but it also foreshadows future conflict in the relationship. It was Anthony who asked to stay in Julie’s home, but he still insists on taking up equal space to his generous host. Moreover, this exchange suggests Anthony’s tendency to gaslight. Hogg cunningly places the camera so we cannot see the whole bed. Who is to say if Julie is, in fact, taking up too much space? We only have Anthony’s word to go on.

Eventually, the couple find a solution: they map out a halfway barrier with the stuffed animals Julie keeps in her room. These childish toys underscore that, at the beginning of the film, Julie is youthful and innocent. As the film progresses, and she begins to mature, the barrier of toys disappears, and the bed becomes a place where Anthony and Julie have sex — something decidedly more adult – Orla Smith

Listen to the perfect companion piece to our new ebook

Orla, M. A., and Alex discuss cringeworthy class relations, celebrate the film’s sound editing, parse the film’s toxic relationship, and much more.

The Souvenir Scene 2: The Venice trip to the opera

Anthony and Julie’s trip to Venice occurs at about the halfway point of the film and marks a fundamental shift in their relationship. Before the Venice trip, the problems in Anthony’s and Julie’s relationship loom silently beneath the surface of their interactions. During the trip, these tensions begin to spill over into reality.

The Venice trip is a romantic getaway that Anthony proposes in the most Anthony fashion: at once romantic and spiteful, thoughtful and manipulative. Julie is at first delighted — her eagerness suggests she has never travelled — but the trip turns out to be Anthony’s attempt to realize his fantasies of their relationship, rather than an opportunity for them to grow closer. Fittingly, the scenes in Venice are filmed differently than the rest of The Souvenir. While the scenes in England are mostly brightly-lit, Venice is moody, jewel-toned, and increasingly dream-like and fragmentary. The few glimpses of the trip we see are wordless and impressionistic. The preparations for the trip take up far more screen time than the trip itself, signalling that the travel itself was underwhelming for Julie.

After watching the couple travel awkwardly on the train and settle uneasily into their hotel room, we see barely a few snatches of their stay in Venice itself. Julie and Anthony are shot from behind, in silhouette. She is clad in a voluminous ball gown, and we hear the soft clack of high heels as they hurry up stairs. An orchestra tunes up as the soundtrack: they are late. He walks several feet ahead of her, never turning back, and she follows as best she can, hoisting yards of ungainly silk. It is ungentlemanly for Anthony not to walk beside Julie and offer her his arm; the pettiness of leaving her to contend with her gown is a sharp contrast to the image of well-heeled gentility that Anthony likes to perform. Coupled with the tension of the previous scene, in which Julie quietly broke down in their opulent suite, we understand that they have had a conflict, and he is responding with coldness.

Throughout Anthony’s and Julie’s trip to Venice, Hogg holds information back from our view. A closeup of the train of Julie’s gown, heavy folds of gunmetal silk slithering over the stone stairs as the conductor’s baton taps his music stand — but this scene is not followed by a wide shot. Though we never see the gown, nor Julie’s or Anthony’s face, the point is made: this attire is so different from Julie’s jeans-and-Oxford-shirts uniform back home. Before we can watch them pass into the auditorium, the camera pans upward to a sign identifying their location. They are sneaking in before the curtain at La Fenice, one of the most famous opera houses in the world. Anthony’s love of opera, and Julie’s indifference to it, is a marker Hogg laid down early in the film. To that end, Hogg cuts off the sequence without a shot inside the theatre. Opera is Anthony’s conceit, and he has orchestrated this outing with himself in mind; the performance has little to do with Julie.

Then the film cuts immediately to a sex scene, one of three in the film, and by far the least intimate and the most alienating. Hogg shoots their sex the way she shoots their walk into the opera: in darkened and disjointed closeups, with a deliberate focus on attire. First, Julie’s back is bent over, naked from the waist up, and Anthony’s hands slide a black lace garter belt down from her waist: it is the garter belt he bought her earlier, which started their sexual relationship. Anthony’s wrists show he is still wearing his tuxedo while Julie is nearly nude, making her bowed pose redolent of subjection. Then we see a shot of Julie’s disembodied legs on the bedspread, clad in fussy back-seamed stockings — a deliberate anachronism in the age of pantyhose, and far too self-consciously seductive for innocent Julie to have selected them herself. Anthony’s hands reappear in the frame, slowly pushing her ankles apart. Hogg cuts again, and his hands gently gather one stocking down over her knee, careful not to rip the delicate fabric. We never see Anthony and Julie together; instead, his hands move over her proprietarily until she is naked beneath him. They kiss, slowly, their faces almost invisible in the dim light, but there is no heat or affection in their embrace.

Throughout the Venice sex scene, Julie is disturbingly passive. We see her back, her unmoving legs, her knee manipulated by Anthony’s hands. Anthony had dressed her, and here, he undresses her. Julie is present but inactive, moving silently according to Anthony’s guidance. It is the culmination of Julie’s role in their relationship up to this point: willing but unquestioning, always following Anthony’s lead.

We never see Anthony’s or Julie’s full face in the frame: they are always cut off or obscured in some way. On the way to the opera, Hogg shoots their silhouettes, but never shows Anthony or Julie from the front or in focus; during their sex scene, Hogg shifts to disorienting closeups of body parts in very dim light. On occasion, we see Julie briefly in profile, half-hidden, but most of the time Hogg shows us isolated body parts, costumed and aestheticized and depersonalized. These fragments of scenes, and fragments of bodies, suggest a breakdown of something fundamental. It feels almost like Julie’s personhood is eroding as she interacts with Anthony.

This will never happen again. The Venice sex scene cuts directly to the bright lights of Julie’s London apartment, and the first time Julie confronts Anthony about what he has done – M. A. Rowe

The Souvenir Scene 3: Dancing in the apartment and the portend of doom that follows

Ironically, the most romantic sequence in The Souvenir is not the dream-like trip to Venice, where the couple has disconnected and disembodied sex, but a casual evening at home. But, this scene is short-lived, taking us straight into Anthony’s descent into heroin hell. It also closely follows the scene in which Anthony at his most manic, furiously scribbling on the floor in the apartment, clearly descending into addiction. The closeness in their relationship is facilitated by Anthony’s addiction — the worse his using, the more vulnerable he becomes, and the more he becomes an accessible lover.

The sequence begins with an establishing shot of the Christmas lights at night, e, twinkling in the street as if out of a Pissarro painting. Inside Julie’s apartment, a blues tune is playing, Willie Mabon’s “Poison Ivy.” The lyrics are somewhat foreboding — “I’m like poison ivy; I’ll break out all over you” — like a cautionary tale of what Anthony will become to Julie. For now, though, the couple enjoys a moment of light, comfortable intimacy; in stark contrast to the scenes in Venice, there is nothing performative about their interaction. Seated lazily on the couch at the back of the frame, Julie has kicked off her shoes and socks, popped the collar on her crisp but comfortable shirt, and rolled the legs of her jeans — her film school uniform. At the front of the frame, Anthony dances for us, wearing his distinctive house coat, carefree and having fun. When she puts up her hand to ask for an invitation to dance, he grabs it like a gentleman, and they begin to swing around the living room.

Hogg gives the pair equal weight in the frame, both in profile, both at a similar height, both moving and enjoying the dance. The frame is split between the reflection of the couple in the mirror and the couple dancing in the living room. Here, the mirror image — the memory, the idealized version of the couple — actually matches the reality, perhaps for the only time in the film.

But like so many scenes of joy in the film, Hogg cuts it short. In a still frame looking out the window of Julie’s bedroom, we hear Julie breathing heavily, in what sounds like sexual satisfaction. Then, we see Julie’s flushed and happy face in closeup, lying down in bed, and peaking under the covers with laughter. It is the first sex scene that is about Julie’s pleasure.

The morning after is eerily quiet: Julie climbs the stairs of her apartment in silk pyjamas, following Anthony’s romantic trail of note paper, but, just as she reaches the window, the Harrods bomb goes off. The apartment, once Julie’s safe haven, shakes, and she is startled — a portend of how Anthony will destabilize her life. In the next scene, Julie takes Anthony to get his next fix, and he walks away from her, further back into the frame, and toward heroin, the romantic moment ended – Alex Heeney

Read more excerpts from the book >>

Liked this article? Get the book on The Souvenir

For more in-depth analysis of The Souvenir plus unprecedented insights into Joanna Hogg’s filmmaking process, get Seventh Row’s new book Tour of Memories: The Collaborative Process Behind Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir.