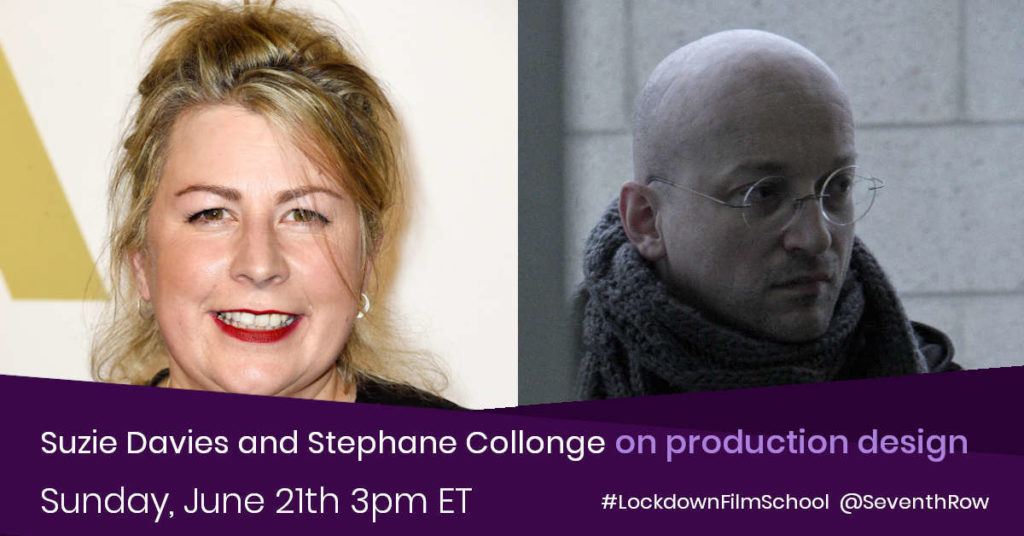

In this interview, production designer Stéphane Collonge discusses his creative process and how the design of The Souvenir was meant to evoke memories. This is an excerpt from the ebook Tour of Memories: The Creative Process Behind Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir. To read the whole interview, get your copy of the book now.

When Stéphane Collonge began his career as a production designer and costume designer, he assumed that he would be hired largely for his skills as a technician and craftsman. Then he met Joanna Hogg. “[When] I met Joanna, she changed everything,” he recalled. “She started to ask me, ‘What do you think? How do you feel about this?’ And suddenly, it was like, ‘Oh wow, I’m also choosing to explore something.’” Hogg brought him into her creative process, encouraging him to explore the emotional and psychological aspects of the film’s story and characters. The pair first worked together on Hogg’s first feature, Unrelated, after meeting through the National Film and Television School’s alumni network, and Collonge has worked on every single one of her films since.

‘Method Production Design’ is Stéphane Collonge’s term for the approach to production design that he developed with Hogg. Like a Method actor, he thinks deeply about characters’ psychology and backstory, and this emotional context informs how he designs the sets. Collonge elaborated, “You explore within yourself who is that person you are trying to make a portrait of. So that person would have that jumper, or maybe they would have bed sheets rather than duvets. It becomes very specific and precise. You see the desk of that person — is it ordered? What is in the drawers?” On Hogg’s first three films, Collonge also served as the costume designer, and he often found that the costume designs would inform the set designs, since costumes design is, as he says, “close up” with the characters.

Hogg’s films involve on-camera improvisation, and the film is shot in continuity, meaning both the narrative and the characters tend to evolve as the film is being made. By necessity, then, the sets and costumes need to evolve concurrently. “Because [Hogg’s] vision is so strong, she can invite reality, chaos, or something that is very new,” Collonge explained. The need to be agile and open to spontaneity, to respond to new changes, is part of what makes working with Hogg so exciting and rewarding, according to Collonge. He also believes that the dynamism and unpredictability of her process helps explain how her films are so realistic and why she is able to elicit such outstanding performances.

In this interview, Stéphane Collonge discusses the relationship between costume and production design, his approach to both creative processes, how the design of The Souvenir was meant to evoke memories. When I talked to Collonge, he was on set for The Souvenir: Part II, and,at one point, was called away by Hogg to revise and develop the production design. After all, it was not set in stone.

Seventh Row: What is your overall process for production design when you are working on one of Joanna’s films?

Stéphane Collonge: As you can imagine, [our collaboration] has evolved through the years. Designing a feature with Joanna is now very much about workshopping the visual storytelling. I would meet with her quite ahead of the pre-production, and we would discuss the story. She has what we call a ‘story document’ that involves direction ideas that are not formatted as a script but that we can share and use as a base for discussion. There are some lines of dialogue, but most of the time, it’s a general description of the scene, and it gives you an overview of the project.

My job with Joanna is to ask the right questions. We do a lot of workshopping, asking, Is that what we are trying to do? Is that the character? How do they evolve? Who are these people?

Joanna’s films are based on things that are very close to her. She’s incredibly precise about the emotional truths of the scene. Each character is always very well defined. It’s always a joy to see who she ends up casting; it is always an incredible payoff. You talk about characters in a very broad sense first, and then it becomes more and more defined as we try to figure out who could play the part. It’s not necessarily actors; it’s sometimes nonprofessionals.

When the general curve of the story and the main characters are defined, I start designing. You know what has to be dressed, built, researched for locations. Once you know what you are looking for, and it becomes very precise, then it could also change dramatically according to what reality gives you. There is this image of the film immaculately discussed, but then you have to be ready to change right at the last minute because you realize the initial [story] you were trying to tell has evolved.

On Archipelago, we were looking for a painting of a big wave. We looked everywhere to find the image of an ominous wave, which symbolises what the family was going through in the film: a change of tide, something that could either deflate and disappear or… crash on them!

We found a painter that had exactly painted this, and we were in the process of printing his artwork on canvas to dress in our sets when my art director found a black-and-white photograph of a large wave, of the same composition and proportions, in the only pub on the island! It was incredible. That photo had been taken by the grandfather of the Lord Proprietor of the island 60 years ago. It was in fact better than our original idea of a painting because in the film, the act of painting is very positive.

Read more excerpts from the book here.