The 2019 InsideOut Film Festival brought together mainstream hits like Rocketman and Late Night with arthouse gems like The Ground Beneath My Feet and Zen in the Ice Rift.

Half the fun of Toronto’s InsideOut LGBTQ+ film festival is the atmosphere. The festival brings out its rainbow-coloured lights to make the normally red curtains on the TIFF Bell Lightbox screens festive, Toronto’s LGBTQ+ community comes out in droves, and even the cinema re-entry tickets are rainbow-coloured pipe-cleaner keys. Still, it’s one of Toronto’s best-kept secrets: the festival regularly sells out, and yet you’d be hard-pressed to know if even existed if you didn’t already know it existed. InsideOut has built up its own little community that has very little interaction or overlap with the broader Toronto cinephile scene.

InsideOut 2019 rolls out mainstream fare from Rocketman to Late Night

This year’s festival was particularly exciting for its mix of both mainstream American films and off-the-beaten-path films from around the world. The opening night film, Rocketman, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, screened at InsideOut before Cannes had even wrapped for the year. With multiple screenings, the film attracted a broader audience of Elton John fans and likely first-time Inside Out attendees. Festival volunteers handed out Elton John-shaped paper cutout masks to everyone going in. Past opening night films have included last year’s poorly reviewed Sundance film A Kid Like Jake and Sundance hit but arthouse underdog God’s Own Country.

The festival’s closing night film, Late Night, felt like more of a publicity grab for the festival than a particularly fitting entry. As a studio film with major distribution (the film has been in Canadian cinemas for almost 2 months now) and A list stars, it didn’t need the platform that InsideOut provides for smaller films; instead, the festival used the film’s high profile to help draw in new, broader audiences. What was a film about two straight women doing in an LGBTQ+ film festival? Still, InsideOut had previously programmed a film by the director of Late Night, Nisha Ganatra, anLGBTQ Canadian filmmaker. Screening Late Night was a way to celebrate a Canadian filmmaker making it big in the US and the important work InsideOut had done to help launch her career. Past closing night films have tended to be indie darlings like Heart Beats Loud and Hello Again, both films that lacked the big-name cast of Late Night.

From The Ground Beneath My Feet to Zen in the Ice Rift

The heart of InsideOut was, as always, the independent and foreign films. The most exciting development this year was the sheer number of films featuring transgender or nonbinary characters, in stories not limited to those of transition. From the Argentine Berlinale winner Brief Story from the Green Planet, to the Brazilian Fabiana, to Italy’s Zen in the Ice Rift, to the story of a Mexican-American woman in The Garden Left Behind, trans characters have become the centre of multiple films, as integrated into the program as LGB stories. Maria Kreutzer’s The Ground Beneath My Feet was a particular standout, as was Vita & Virginia, a fascinating film though not without its problems.

Looking back at this year’s program, here’s a taste of some of the festival’s highlights and disappointments.

Rocketman: InsideOut 2019 Opening Night Film

It wasn’t a good sign that I spent much of Rocketman thinking about how incredibly talented and underused Jamie Bell is as an actor — especially given that Bell was only playing a supporting character. Yet Bell was the most compelling screen presence in a film that regularly put together two of today’s most cardboard heartthrobs — Taron Egerton and Richard Madden — in scenes they had to carry on their own.

A jukebox musical biopic about Elton John’s rise to fame, dalliance with sex and drugs, and his lifelong friendship with his lyricist (Jamie Bell), Rocketman felt more like Elton-John-approved propaganda than a serious interrogation of his character and career. The film’s framing device was a neat idea, though poorly executed: after checking himself into rehab, John looks back on his life with glittery nostalgia in group therapy. But because nobody else in his group ever talks, and his storytelling felt forced rather than part of a real catharsis, the idea was unmotivated.

But it allowed director Dexter Fletcher to take fanciful liberties with the way he recounted John’s life story: John literally floats on stage at his first major concert in LA; his performance at the Dodgers stadium is covered in glitter and shot with spinning cameras. The film’s heightened, theatrical aesthetic reminded me of last year’s Postcards from London, which also used stylised filmmaking — often looking like the characters were on a film set rather than in real locations — to put us in a queer space for the character’s sexual awakening.

Late Night: InsideOut 2019 Closing Night Film

Emma Thompson stars as the prickly Katherine Newbury, a legendary late night host celebrating the 30th anniversary of her show right as it’s being threatened with cancellation. Enter Molly Patel (Mindy Kaling, who also wrote the script), a diversity hire to the all-white all-male writing team who forces Katherine to shake things up, get political, and stop sitting on her laurels. Kaling’s script eschews the conventional mentorship narrative; Katherine is fairly awful to Molly, only taking her seriously when forced to for publicity reasons. But the two women ultimately develop a grudging respect and a working partnership.

Between The Children Act, Years and Years, and Late Night, I am very much here for the Emma Thompson Wears Power Suits stage of Thompson’s career. Unfortunately, Late Night has little to offer beyond Thompson’s wardrobe, and of course Thompson herself. Still, any showcase for the prodigiously talented Thompson is worth seeing. It’s especially fun to see her revel in the role of a brilliant misanthrope who is losing touch with her audience. There’s also a lovely subplot between Katherine and her aging husband (played by the wonderful John Lithgow) who remains 100% in her corner, a role so rarely seen in the movies.

Vita & Virginia

When Vita & Virginia premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival last year, I named it one of the festival’s 20 best acquisition titles. After the film picked up distribution, I saw it a second time at InsideOut, which only made me more effusive about the great performances from Gemma Arterton and especially Elizabeth Debicki. It also made me aware of why the film didn’t fully click.

Though Vita & Virginia spotlights the romance between 1920s authors Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf, the film is surprisingly at its best when it deals with everything but their relationship: — the women’s complex, modern marriages to loving husbands, their relationship to writing, and more. The film’s greatest strength is as a showcase for Debicki, one of the most talented actresses working today, who perfectly embodies Woolf’s genius and vulnerability.

I went deep on the film on a recent podcast episode with Mary Angela Rowe and Orla Smith. Vita & Virginia is currently rolling out across the country except for in Toronto and Vancouver; it will be on VOD in November.

Zen in the Ice Rift

Zen in the Ice Rift is a quiet film about a teenage hockey player dreaming of going pro eschews labels for its protagonist, Zen (Susanna Acchiardi), who feels like a boy in a girl’s body. Sporting short hair, androgynous looks, and an athlete’s muscular build, Zen presents as genderqueer. Writer-director Margherita Ferri holds back the details of how Zen sees himself at the start so that we see Zen in much the same way as his peers do.

Things for Zen are especially complicated by the fact that his passion and career path involve playing a gender-segregated sport. In high school, he is the only “girl” on the boy’s hockey team, is segregated to the “girl’s” changing room, where he feels uncomfortable undressing, and can only hope to play professionally for the women’s national hockey team. As Zen notes, there is no changing room for someone like him — and there’s no hockey team, either. It’s a crucible for bullying, especially in a homophobic small town where being a lesbian is seen as an excuse for teasing, let alone a non-conforming gender identity.

Zen’s outsider status has kept him closed off from other people, always lonely and a loner. As the title suggest (Zen in the Ice Rift), Ferri uses the local ice rift as a central metaphor for Zen’s eventual opening up to other people — an image that is beautiful and effective, if obvious. As Zen starts to let a classmate in, an ice starts to melt into a rift, but that rift is dangerous and so is Zen’s newfound vulnerability.

The Ground Beneath My Feet

Following in the footsteps of Toni Erdmann, writer-director Marie Kreutzer’s The Ground Beneath My Feet is also a German-language film about a woman so absorbed by her consulting job that she’s erased herself from her own life. In The Ground Beneath My Feet, Kreutzer is constantly distancing us from Lola: keeping her off-centre in the frame, often in profile, only ever centred when she’s far away from us, at the back of the frame. Kreutzer will even often hold a shot while Lola steps out of it: it’s like Lola is trying to get out of her own film.

Lola (Valerie Pachner) has done everything in her ability to fit in, toe the company line, and remain in the background: she exercises vigorously to maintain her slim physique, wears crisp black and grey suits that ensure she never stands out, has perfectly coiffed but not obtrusive hair, and tries to keep her personality separate from her work life. As a queer woman working in a patriarchal work environment, where clients freely spout sexual advances as if it’s completely acceptable, Lola is aware that revealing herself at work could be detrimental to her career. And as the sole caretaker of her paranoid schizophrenic sister, she knows even the rumour of family mental health problems could cause trouble at work.

Kreutzer draws parallels between the self-imposed prison Lola lives in and the involuntary one of her sister, Conny (Pia Hierzegger), in a psychiatric institution. Conny has no control in her life: the hospital sets her meals, her schedule, her sleeping habits, and she can’t leave. Even Conny’s mind isn’t her own. Lola, on the other hand, is financially independent and mostly mentally sound — though she starts to worry about her own stability. Yet Lola feels like she is under constant scrutiny: her office is full of windows instead of walls, and Kreutzer often shoots Lola through the windows, so we can see her glass cage. In an attempt to keep herself out of her work, Lola lives out of a suitcase, is in a relationship with her boss who feels as undefined as Lola — also blonde, beautiful, and seemingly without interests outside of work. Conny may be literally imprisoned, but Lola is also caged: she must work hard to present a carefully curated front, designed to fit into often misogynistic societal expectations of women. Her entire life is constructed to present the right appearance, as someone aware that she’s constantly being looked at. The Ground Beneath My Feet thus raises the age-old and sadly still relevant question: can a woman ever be truly free when living in the patriarchy?

Keep reading about great queer cinema…

Call Me by Your Name

Read Call Me by Your Name: A Special Issue, a collection of essays through which you can relive Luca Guadagnino’s swoon-worthy summer tale.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Read our ebook Portraits of resistance: The cinema of Céline Sciamma, the first book ever written about Sciamma.

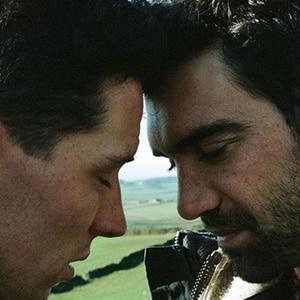

God’s Own Country

Read God’s Own Country: A Special Issue, the ultimate ebook companion to this gorgeous love story.