Alla Kovgan discusses restaging and shooting dance excerpts for her 3D doc Cunningham, including creating the camera choreography and capturing the sound.

I first encountered the work of choreographer Merce Cunningham when I saw the Merce Cunningham Company perform his piece “Nearly Ninety” in 2012. Set to a score from John Cage — his long-time collaborator known for passing off noise as music, sometimes even gunshot noises — though not choreographed to his music, the piece was unlike anything I’d ever seen before. It was dance that was somehow independent from music, where what unified the dancers wasn’t immediately obvious.

As the piece unfolded, order seemed to appear among the disorder. There would be a trio where all three dancers twirl around in unison with an arm raised, but they will each have slightly different arm movements or different degrees of extension of the arm. The more I became conscious of this order, the more I found its defiance of complete order beautiful and intellectually challenging: it created a richer, more complex landscape of movements to follow. You have to constantly ask yourself “Are the dancers moving as one? If so, how?”, and only rarely expect the answer to be “yes, in every way.”

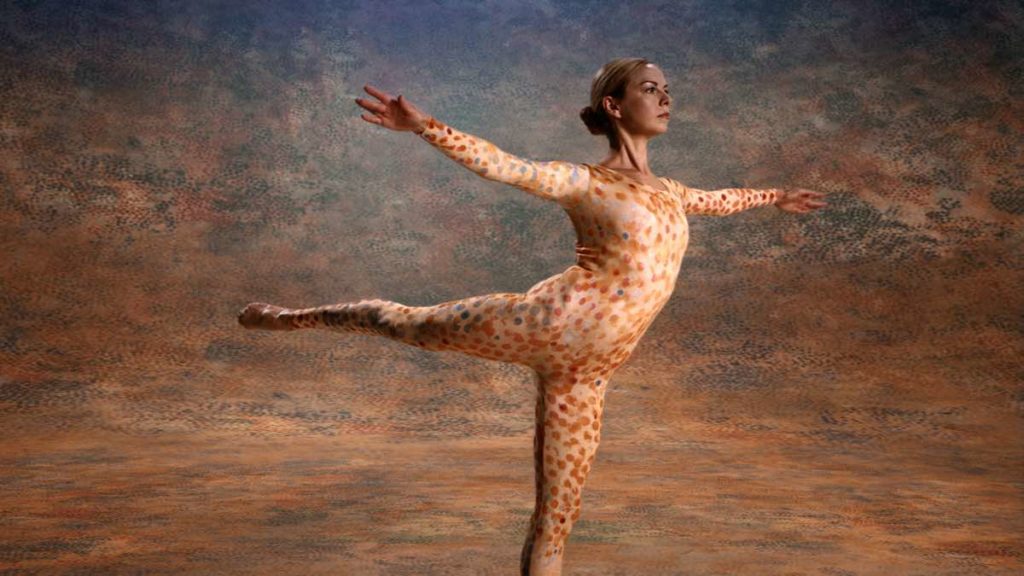

Alla Kovgan’s new 3D documentary, Cunningham, attempts to make sense of this disorder — not as it works in an individual piece, but how it served as an organizing principle throughout Cunningham’s career. By recreating excerpts of the dances in locations that emphasize some of the ideas behind the dance, and creating yet another dance between camera and dancer, Kovgan brings us inside the choreography in a way that is entirely different from how you’d experience it on stage — perhaps ideal for someone new to Cunningham’s often alienating approach. Working with the 3D stereography team from Wenders’ Pina and 12 dancers from the Cunningham Company, Kovgan has restaged pieces of Cunningham’s groundbreaking choreography devised between the 1950s and the 1970s.

In Cunningham, Kovgan mixes archival footage of Cunningham and his company dancing with interviews, letters, and voice recordings, creating a kind of 3D collage to contextualize Cunningham’s work. This is then mixed in with modern restagings of excerpts from several of his most famous works, performed in the wild rather on stage — much like what Wenders did with Pina. The film is most alive when it stays with the contemporary dancers and these restagings. Kovgan understands that you can’t capture dance on film so much as translate it, and the dance between the camera and the dancers makes for compelling viewing — bringing you inside the performance, rather than delivering a documentary of existing Cunningham pieces in full.

Kovgan succeeds in giving strong context for Cunningham’s eccentric choreography, positioning it within modern art of the day — after all, Robert Rauschenberg worked with Cunningham on the sets and costumes — rather than treating it as a curiosity that could otherwise appear to have emerged in a vacuum. But this contextualizing often feels boring compared with the dance recreations which are so vivid and exciting — especially given Kovgan’s dynamic approach to sound, lighting, and camera movement.

When the film had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival last September, I sat down with Kovgan to discuss bringing Cunningham’s work to the screen in 3D, the opportunities and limitations of the technology, and the process for translating dance from stage to screen.

Seventh Row (7R): Where did the idea come from to do a documentary about Cunningham and to do it in 3D?

Alla Kovgan: I never imagined making a film about Merce Cunningham. I know Charlie Atlas quite well, and he and Merce made quite a few films together. I used to run a dance film festival in St. Petersburg, Russia. I remember bringing Charlie to Russia in 2006 to show his film, and I just kept thinking, How did you guys do that?

Fundamentally, Merce is a choreographer who works in space. You have 16 people going in different directions, so what do you actually show [on film]? There was a Rockefeller Commission with Dance Film Association to make a 3D film with a New-York-based choreographer, and I was actually never thinking about it because I was working on something else. But I went to see the last performances of the Cunningham company at Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York, and it crossed my mind that 3D and Merce Cunnigham would work. I was like, My god, he’s so good at working with space, but there’s no way to capture it!

I actually think there’s no way to capture dance [on film] period. You can engage with dance in cinematic terms, but it’s a different thing. 3D slows down your perception, and it works so well in space with long takes. I thought something clicked in that moment.

I was also looking at 14 beautiful dancers who were the last generation of Cunningham dancers to be trained by Merce himself. The next month, they would be out of work, and all of that work would be gone because at the time, it felt like they were never going to dance again. So there was a kind of urgency because they were at their prime; they were beautiful; and they carried something of Merce himself inside their bodies. That was the biggest moment. Merce embraced every technological advancement of his time, from 16mm to motion capture. I felt like, had he been alive, he would have been interested.

7R: How did you think about what parts of a Cunningham dance you were going to be able to capture on film?

Alla Kovgan: I’ve done other dance films in my life and have been around dance for over 20 years, so I know it is impossible to make movies about dance. It’s possible to make movies about dancers and choreographers as people. People can learn about them.

But to actually give an experience of dance, you can’t capture that on film, because dance and cinema are ultimately in conflict because they work with time differently. They work with space differently. One minute on film and one minute on stage is completely different. It’s impossible to compare.

I immediately decided we were not going to capture anything. We were going to translate Merce’s ideas into cinema. We were going to think about Merce’s work in cinematic terms. We were going to do what Jerome Robbins did for Bob Fosse. We were going to think of choreography on screen. I was really inspired by this period when Merce wasn’t Merce yet, but he was a young dancer in New York and becoming Merce the choreographer. This period was between 1942 and 72 — from the first concert that John Cage and Merce Cunningham gave together, to when the last founding member of the Cunningham company, Carolyn Brown, left. That was, according to Cunningham historian David Vaughan, the end of an era.

That’s the time when I felt Merce didn’t often know what he did, but was figuring it out. That process was very interesting to me. It also happens in New York at a time that was the rebirth of American art, and he’s with all these artists as the dance person among them. That was another big draw. And then finally in 72, in the ‘70s, Merce picked up the camera himself. He was very interested in the camera. He thought it affected his choreographic process, so all the films he made with Charlie, and Elliot [Caplan], and all these other people came later. I didn’t want to go to that place.

We said very early on with directors of choreography that we were just going to try to tell the story of Merce through his work and think of his work in cinematic terms. We went through 80 works, identifying first 22, then 14 iconic works [that were] very important for his development and process and also life story. Out of each dance, we picked excerpts that were to be re-imagined in 3D. Behind each dance, we identified the physical question Merce posed and then thought about this physical question and the idea behind the dance in cinema terms. That’s where the locations come in, because cinema doesn’t happen on stage.

7R: How did you decide the locations you wanted to use to stage Cunningham’s dance sequences?

Alla Kovgan: If it’s a dance with the action of falling, how would cinema deal with falling? You can refer to many films that work with that idea, so we put it on the rooftop, thinking of Hitchcock. If it’s about layering, pine trees are perfect because we amplify the idea. If it’s about being enclosed, we made a maze. We tried to use locations as a way to highlight the idea [behind the piece].

Creating the choreography between the camera and Cunningham’s dancers

7R: How did you decide how to move the camera when shooting Cunningham’s choreography?

Alla Kovgan: That was a very deliberate process with the directors of choreography and the DP. The camera is stupid; you have to tell it where to move every second; otherwise, it doesn’t know, so we had to identify that. Sometimes, we lost dancers in the frame, but it didn’t matter because we were not trying to capture choreography; we were trying to capture the experience of the idea behind the choreography, and that’s a very different intention.

Sometimes, it felt like the camera was inside the dance and people come and go and enter. We wanted to create that sense of proximity that would allow people to enter the dance and that guided a lot of the decision-making.

Of course, you are also in space. Once you are in a location, the space becomes part of the composition. Sometimes, you have to deal with pillars, and pillars are not possible to manage. This all becomes part of the choreographic world, and that becomes beautiful because Merce was open to chance, to things happening. The three of them — [Robert] Rauschenberg, Cage, and Cunningham — were interested in what would happen if you bring all these things together. Sometimes, there is only so much you can control.

7R: At some points, you can see multiple dancers and how they are moving together and within the space. At other times, we are coming in close and focusing on the movements of a particular dancer. How did you think about when to focus on details and when to focus on the bigger picture of Cunningham’s choreography?

Alla Kovgan: Very rarely was the choreography broken down. We didn’t alter any of Merce’s choreography. We might have spaced it differently because we were in a different space, physically. Again, if you have a solo, it’s very easy. But even with the solo, are you close or are you far?

It’s not really defined if I need to see somebody close or far. It was always about how you work with time and what keeps you interested. If you want to see a Cunningham dance, go and see them. People still perform them. What we are trying to do is bring the experience of the ideas to cinema.

When you think about [the dance] “Winterbranch,” [the camera] starts very low, and you go very high. All we do is create the idea of falling, but it’s a very long shot. You would never look at her doing that movement if we didn’t do something to create that idea.

Capturing the sound of Cunningham’s choreography

7R: How did you think about sound? It’s really wonderful how you can hear the dancers’ bodies and how they are touching the ground in a way that is somewhat similar to being in the room with them.

Alla Kovgan: Movement doesn’t come without sound. It amplifies the visceral quality, of course, but it can also distract. If somebody is like boom, boom, boom, all of a sudden you only look at their feet, and in film, it is even more so than on stage.

I always record foley while the dancers are there. I call them sound takes. We do our takes first. The sound is recorded, but we give instructions: all kinds of things happen, [and] it’s loud. Once everybody is done, we record sound takes with the cameras off. The sound people are very close to the dancers, and they can actually record the steps. I’m a big proponent of doing it while all the real dancers are there versus doing it afterwards in the green room with foley sessions. It’s much better to do it with the actual people, to keep a sense of authenticity of the movement because I’m all about the best performances.

Of course. Cunningham and sound is very complicated because he didn’t work with music or sound. He believed there’s an internal rhythm which the action produces, which is of course true. You don’t have to have a drum beat to cross the street; you just cross the street, and choreograph yourself to an internal rhythm. I was very adamant about keeping the original score. I couldn’t imagine putting Philip Glass on Merce Cunningham. People were saying it’s too avant-garde, but I feel all the scores are part of the work. Why do you suggest taking away [Conlon] Noncarrow’s music from “Crises”? It’s like taking Tchaikovsky away from Swan Lake! Just because you don’t like it, doesn’t mean you can do that, especially working with a choreographer who’s not there anymore. That was the piece! We can’t do anything; this is it.

I can take away the music though. Sometimes, we would take it away because it was too much for the movie world. But Merce did so many events where he would pull excerpts from different dances. He would come to a location and assess the location and see which excerpts would work. They could perform it with no music and just the sound of the environment, or they could commission new music. I felt that gave us a license, in a way, to work freely because we can create an environment.

With “Winterbranch,” for example, there was a feeling that there must be a club downstairs. The club downstairs can play anything, and we immediately create an environment. I tried not to be didactic with sound — step — sound, none of that. I tried to create more layers in the soundscape rather than writing music. We didn’t write music to dance.

7R: For the sound takes, the dancers would do the whole choreography?

Alla Kovgan: It would be like surround sound. We would have mics all around. We would have sound people really close to get the steps, because on-screen, you are supposed to be close, so you hear. If you record sound really well, you have material to work with. You can push them away in space, especially in 3D, or you can bring them really close.

[For the dance sequence] in the tunnel, for instance, the sound is much louder than you would ever hear in that proximity, so we cheat. Because we have the sound takes, you can hear him much earlier than we get to him [with the camera, which is pushing in toward him]. Again, we create an experience. It’s all very choreographed in this sense, from the distance, to the sound, to the lights. Everything. It’s painstakingly worked out.

Cristian Mungiu’s sound takes

Cristian Mungiu also does sound takes for his films in which the actors do the choreography for the scene minus the dialogue.

The opportunities and challenges of shooting in 3D

7R: Something that struck me about one of the early dances in the film was the use of the spotlight. In 3D, it’s amazing. I’ve never really thought about light on film as being three-dimensional. Of course, that’s something you see on stage all the time. It felt all the dances you were capturing were lit in a very specific way to make use of that.

Alla Kovgan: We had a great DP [Mko Malkhasyan]. We’ve worked together now for 13 years, so we know each other, and he has worked on all the dance films I’ve ever made. Light becomes another choreographic element. We had never made a 3D movie before so we could only imagine what it is going to work with.

We had a director of stereography, Joséphine Derobe, who worked on Pina. She was great. She was advising which direction we need to point the light. It’s technical, too, because if a flare hits one camera and not another, you are going to have a blind spot. There’s two cameras strapped together, so you have to be a bit careful about how you do these things.

Light became part of the choreography, the composition. This is demanding choreography. They can’t do it over and over and over and over again. There was a moment where they did 14 takes, but sometimes, they would say they could only do it five times: that’s it. One time, a dancer was injured, so there was only one time. We had a physical therapist on set, and she did wonders, but she said we could only do it one time.

There was a trepidation among everybody, the whole crew, that they were witnessing a performance and that was different from other film shoots. And also, once the dancers are warm, you have to go. You have no time to dilly dally.

Working with dancers is very different. It wasn’t that they danced, and we just filmed them. Everybody knew what the shots were; everybody had storyboards. When we got to the day of shooting, we knew everything that was going to happen. The more we knew, the more interesting possibilities opened up. I wish we had more shooting days. I wish we had more time because I think there were some things we didn’t have time to do. There was so much potential.

7R: Were there limitations to 3D?

Alla Kovgan: Especially with Merce. I was jealous of Pina Bausch because some of the crew worked on Pina, and they would say, “We remember studying the music. We remember the music goes woooo, and we go.” Here, we don’t have anything, so the hardest thing was for the crew to learn [the choreography without the help of music] because they have to learn the movement.

There’s the choreography of the dancers, but there’s also the choreography of the crew. The guys with the crane or with the steadicam, they have to know [the choreography of the dance] because they can actually get hurt [if they aren’t in the right place at the right time].

When we did the test in 2015 of “Summerspace,” we learned that the crew could not remember more than 40 seconds of choreography. There were some one minute shots or even longer, but those shots were very simple: you just go from here, and you go up, and we would count for the crew, not for the dancers, how long did this take, so that you would arrive [at the right time]. She’s [the dancer is] consistent; she’s going to put her hands up, but [the camera operator has] got to arrive at that moment, and you’ve got to be still.

Nobody [in the crew] could understand the idea of stillness because they come from commercials where nothing is ever still. When I say you have to arrive and be still, still means still, it’s not like half-pregnant. You are either pregnant or not. That was hard for people to do. I felt like that was hard and took time. Sometimes, you had to redo and retry, but the dancers can’t re-try all the time.

So how do you choreograph the crew and how do you bring them together? And because you are on a budget, and the clock is ticking, and you only have this one day on this one location, and you don’t have enough time for rehearsals, the crew would say there was not a single day that was relaxed because they had to dance, too. And most of them are guys.

7R: Did you have music on set when they were doing the dances?

Alla Kovgan: Only in three instances. Whenever Merce choreographed to music, then we had playback. But then we did sound takes without playback, because we needed it clean.

7R: All the dancers in the film were in Cunningham’s company?

Alla Kovgan: We had 14 dancers. 12 were in the Cunningham company, one was in the understudy group which Merce also trained, and one is a new dancer who was trained by Robert [Swinston, who spent 31 years with the Cunningham company]. We also had guest dancers. Robert Swinston started a new company in Angers, France around 2012, so he’s trained them now for five years, which is interesting because it’s a different generation. And at the end [of the film], on the rooftop, we had 26 Cunningham veteran dancers.