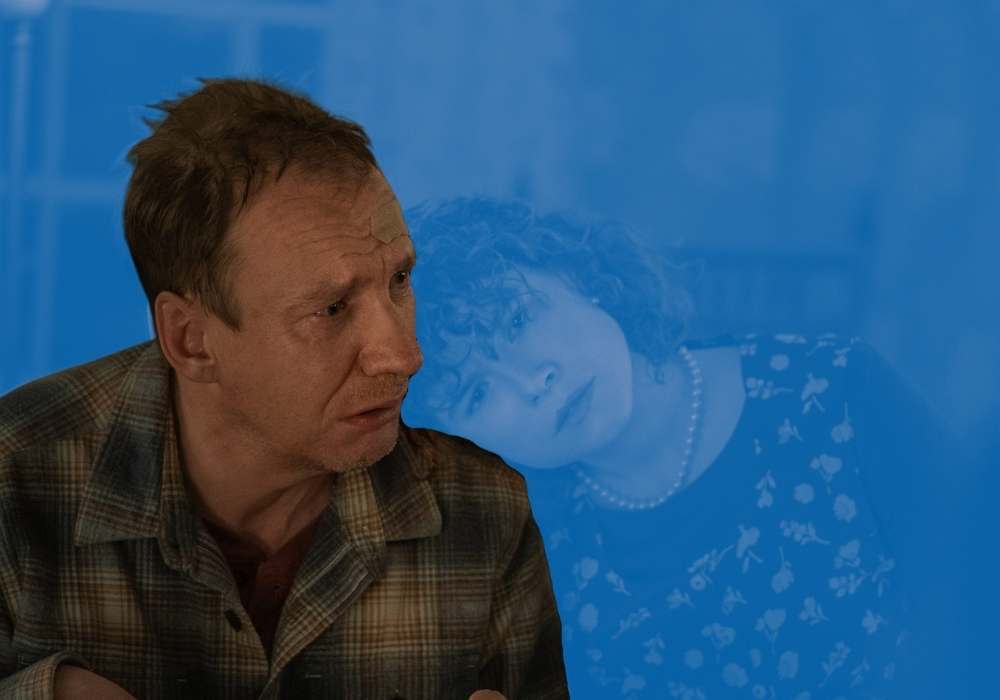

In Proxima, Matt Dillon and Lars Eidinger play the rare male characters who are flawed, privileged, and yet still empathetic.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

Alice Winocour’s portraits of men in Proxima are the rare case that acknowledge the men’s privilege and entitlement, and how that affects their interactions, while still presenting them as well-meaning, kind-hearted grown-ups. Lars Eidinger plays Thomas, Sarah’s (Eva Green) ex-husband with whom she co-parents, and Matt Dillon plays Mike, the astronaut team leader that she will be going to space with. Both men make not great first impressions, but Dillon and Eidinger layer nuance into their performances to show these men as flawed people with empathy, whose flaws are highly connected to their privilege.

We first meet Thomas when Sarah pulls him out of a meeting at work to talk to him about the logistics of caring for their daughter while Sarah is in space. He reluctantly excuses himself, frustrated, as he quietly asks her why she’s there, sighing repeatedly. Before she even gets a word in edgewise, he’s decided she’s there to harass him about canceling on their daughter at the last minute, his back to her at first, and then continues to make excuses for his past behaviour by avoiding eye contact with her. When he finally looks at her, there’s a terrific exchange: she beams, and you see it dawning on him what’s happened, that she’s going to space, and he smiles, excited for her before giving her a hug, a marked change from his previously unwelcoming body language. As they negotiate, he once again makes declarative statements, only occasionally looking at her. He’s soft-spoken but passive-aggressive, if reasonable.

The next scene introduces us to Mike, making a speech at a party celebrating the impending launch. He comes off as incredibly entitled as he reduces Sarah to a woman who cooks in his speech. After knocking on the window to encourage Sarah to join him at the barbecue, he introduces her to his wife, then looks away, before moving away to let them talk; he clearly means well, but it’s an awkward thing to leave his new colleague with his wife just because they’re both women. Later, when Sarah first meets him at training, he tries to offer her some friendly advice, indicated by his softer, lower voice. When he’s interrupted by their colleagues, he’s visibly uncomfortable that they have company, and keeps a low voice for a semblance of privacy. But he comes off as arrogant by never explaining how he feels. He doesn’t realise this until after the fact though, and his coaxing voice suggests there’s a kindness behind his sentiment.

Both Thomas and Mike deepen, though, when we get to see them in more private settings, where their charisma and generosity really shine. When Sarah drops off her daughter with Thomas, he’s grinning when they arrive. He cares about his daughter even if he still needs a pat on the back for it from his ex. When he and Sarah talk in the kitchen, with hushed voices, we get a sense of the relationship that once was — both why they were together and why they broke up. He’s charismatic, making jokes, offering her tea, and leaning in as he acknowledges their similarities. There’s affection in his conspiratorial tone.

Later in the film, Sarah calls Thomas after a particularly rough day. We only hear Eidinger’s voice here, but we can hear in his pauses and soft voice that he’s trying to be there for her but doesn’t quite know how. He answers and listens to her like a partner, giving her a loving pep talk in just a few well-chosen words. He doesn’t explain or hesitate, letting their shared intimacy show through how little he needs to say. When she’s still weeping afterward, he pauses to offer her slightly more cliched comfort, sensing it’s what she needs. We also see him with their daughter, often half-distracted, but just like he did with Sarah on the phone, seriously listening to her, answering her questions, providing her comfort.

Eidinger regularly shows us Thomas’s emotional intelligence. When he and their daughter visit Sarah in quarantine and their daughter is uncharacteristically quiet, he looks back and forth between them, before concluding his presence is interfering with their relationship. And when Sarah goes into space, he bursts into tears, holding his daughter’s hand as they both experience this incredible moment in her mother’s life. It’s a small, quiet moment that reveals the sensitive man who is so proud of Sarah — something he showed us in his first scene, too — that could be overplayed by a lesser actor.

As the film progresses, Dillon strikes the perfect balance between Mike’s public persona — competitive, eager to be the centre of attention, always certain in his movements and speech — and his more private persona, which is a more thoughtful, kind, soft-spoken version of himself. Dillon tends to shift modes with tone of voice and posture: in public, he’s louder, straight-backed, and takes up more space; in private, he drops his voice to almost a raspy whisper and slouches, leans in, and sometimes even moves physically closer without crossing boundaries. Dillon shows us Mike the lover of poetry, Mike the team player, and Mike who is completely oblivious to the privilege he holds as someone with a wife to care for the children as a full-time job when he’s gone.

Proxima is available on VOD in Canada and the US, and on Netflix in the UK.

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch great films and performances (like Matt Dillon’s and Lars Eidinger’s in Proxima) at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.

Click here to subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter.