From Night Raiders to No Ordinary Man, Seventh Row’s editors pick the best Canadian films of 2021, as well as the best to world premiere in 2021.

Read all of our best of 2021 coverage.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

In the last decade, the Canadian film industry has transformed from the crappier version of Hollywood to one of the most exciting sources of emerging filmmakers. It’s for that reason that we published our ebook The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook, which documents a year (or two) of great films to come out of the (illegitimate) state of Canada.

In the few years since, the industry has only become more exciting, especially in the realm of documentary filmmaking (e.g., this year’s The Meaning of Empathy, No Ordinary Man, Still Processing) and Indigenous filmmakers, who make up almost half of our lists of both the best Canadian films released in 2021 (four films by Indigenous filmmakers; one co-written by an Indigenous filmmaker) and the best films to world premiere in 2021 (five by Indigenous filmmakers). Though these (often emerging) filmmakers continue to be underfunded, their output continues to be extraordinary — so much so that one wonders just how amazing the films could be with proper funding.

Our list of the best Canadian films released in 2021 range from Indigenous sci-fi (Night Raiders) to political satire (Québexit) to revenge horror (Violation) to vérité fiction (Anne at 13,000 ft.). Eight of the films are directed (or co-directed) by women and only one film is Québécois despite years of francophone cinema dominating auteur-driven Canadian cinema. Six of the films are first features, a strong indicator of the large pool of talent in Canada just waiting for more and better opportunities. Notably, actress-director-writer Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers, whose fiction debut, The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open, made our list of the best releases of 2019, tops our list this year with her feature documentary Kímmapiiyipitssini: The Meaning of Empathy, and stars in our #10 film, Night Raiders.

While most of the films featured in The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, then seemingly the showcase for Canadian cinema, a few premiered elsewhere. Increasingly, the best Canadian films no longer even screen at TIFF, let alone premiere there, opting instead to screen at international film festival (e.g., Night Raiders premiered at Berlin before bowing at TIFF) or regional film festivals with better Canadian programming (e.g. Festival du nouveau cinéma, Sudbury Film Festival, Vancouver International Film Festival). Of the films released in 2021, only half screened at TIFF; among the Best Canadian films to world premiere in 2021, only three screened at TIFF. Notably, three of the five Indigenous-made films to world premiere in 2021 skipped TIFF.

Get your copy of The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook.

Best Canadian films released in 2021

10. Night Raiders (Danis Goulet)

From the introduction to our interview with Danis Goulet: “While Barnaby’s genre-crossing Rhymes for Young Ghouls looked at the horrors of residential schools — the schools that Indigenous children in Canada were sent to after being torn from their parents — from the perspective of a teenager determined to avoid going to one, Goulet uses sci-fi to look at this from the perspective of a mother forced to give up her child. In Night Raiders, Goulet crafts a poverty-stricken world of the near-future where surveillance drones are everywhere, a militaristic police force is under constant patrol, and nowhere is safe. Here, all children — not just Indigenous children — are permanently separated from their parents and sent to “academies,” that look like prisons, for schooling that seems synonymous with military training. That also means that the multicultural, multi-racial ‘student’ body looks like the film’s audience, which makes the school pledge, “One nation, one language,” particularly creepy. Ironically, the absolutely horrifying “academies” still seem almost paradisal compared to Canada’s residential schools.” Read the full interview.

Night Raiders is now available on VOD in Canada, the US, and the UK. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

9. Still Processing (Sophy Romvari)

From the introduction to our interview with Sophy Romvari: “In Sophy Romvari’s personal documentary, Still Processing, she holds memories in her hands. After a long negotiation with her parents over her desire to make a film reflecting on her two older brothers’ deaths, her father presents her with a box of photos, videos, and film negatives. We watch as, for the first time, she takes them out. In black and white photographs taken by her father, we see children at rest and play. In one photo, a young Sophy is captured in closeup, looking directly into the camera. It’s a confrontational image, and given the film’s subject, it’s hard not to read melancholy in her expression. The photos capture an almost foreboding doom. They capture fleeting expressions that are transformed by events that follow.” Read the full interview.

Still Processing is available worldwide on Mubi.

8. Violation (Dusty Mancinelli, Madeleine Sims-Fewer)

Violation, a bold addition to the rape revenge film canon, has been on a rocky journey with the Seventh Row team. We first published a mostly negative review by Alex at TIFF 2020, in which she praised the ideas the film introduces in the first act, but expressed disappointment in how the film then gets lost in gratuitous violence. Then, after Seventh Row writer and regular podcast guest Lena Wilson expressed adoration for the film on our Sundance 2021 episode, and later reviewed the film for the New York Times, Alex started to warm to the film. That’s what led me to watch and really like it a few weeks ago (I’m more enthusiastic about cinematic blood and guts than Alex is).

I wrote an essay in our ebook Beyond empowertainment: Feminist horror and the struggle for female agency about the changing face of the female monster and how many films sand off the edges of these ‘monsters’ by making them cold-blooded sociopaths. I argued that the violence these women perpetrate is less interesting if they don’t feel any conflicted emotions over it. Violation is the perfect answer to that complaint. It follows Miriam (Madeleine Sims-Fewer) in the wake of being raped by her sister’s husband, who tries to convince Miriam that it was a consensual act. Her revenge is bloody — you’ll need a strong stomach to get through the second half of the film. But she also screams and cries throughout, conveying a tangled mix or rage, doubt, disgust, and sadness as she butchers her rapist. It’s a potent counterpoint to rape revenge films that try to dilute the frighteningly complex feelings a victim of sexual violence feels toward their rapist. At the same time, it asks us to question if completing an act of revenge will offer Mirian any catharsis, or if there’s just more emptiness waiting for her on the other side. Orla Smith

Violation is now available on VOD in Canada, the US, and the UK. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

7. Anne at 13000 ft (Kazik Radwanski)

From the introduction to our interview with Kazik Radwanski: “In Anne at 13,000 ft, Anne (Deragh Campbell) suffers from an unspecified mental illness (likely along the lines of bipolar disorder), and she’s reassimilating into everyday Toronto life after being institutionalised. Work, responsibilities, and socialising can be quite overwhelming for Anne. The choppiness of the cutting and the speed at which we whirl through the eponymous Anne’s life is fitting for such an unstable character.

Radwanski shoots most of the film in handheld closeup, so we’re trapped in painfully close proximity to Anne as she enters uncomfortable situation after uncomfortable situation. Sometimes, we watch Anne putting others on edge, like the intense speech she gives at her best friend’s wedding reception, or her forwardness with a potential boyfriend (Matt Johnson). Sometimes, we watch others making Anne nervous, like several of the men she encounters in the film. Often, it’s less easy to place blame on either side of the clashes this volatile young woman has with those around her: is it her instability, or their insensitivity, or both? It’s this uncertainty that makes Anne at 13,000 ft so anxiety-inducing.” Read the full interview.

Anne at 13,000 ft is streaming on Mubi in the UK, Ireland, Germany, Italy, France, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Columbia, Chile, and more. It will be released on VOD in Canada and the US in 2022. The film is available to rent at the TIFF Digital Lightbox. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

6. Bootlegger (Caroline Monnet)

Caroline Monnet’s feature debut, Bootlegger, follows a young Indigenous lawyer, Mani (Devery Jacobs), who returns to her home reserve, after years living away, in order to complete her graduate school research. On the reserve, alcohol has been banned — not by the Canadian government, as was the case in years past, but by the Indigenous leaders themselves. Mani is trying to encourage the creation of a referendum to let the community decide whether to keep the ban on alcohol which echoes colonialist history.

Bootlegger is thoughtful in its exploration of what it means to become detached from your home as an Indigenous woman, as well as how Indigenous people can end up becoming complicit in their own colonisation because so few options are available to them. The film also positions alcohol as just one way in which the community is being destroyed (e.g., forestry is another). Jacobs is fantastic, as always, here speaking multiple languages. The film is also gorgeously shot. Not all of Monnet’s ideas are fully explored, but it’s certainly a conversation starter and essential viewing for Canadians. Alex Heeney

Read Alex’s profile of Bootlegger and Reservation Dogs star Devery Jacobs.

Bootlegger will be released on VOD in Canada in 2022. It is still seeking international distribution. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

5. Quebexit (Joshua Demers)

From the introduction to our interview with Joshua Demers: “Canadian satire on film is still very much in its infancy, with Philippe Falardeau’s brilliant 2015 film, My Internship in Canada, essentially hailing its birth. With Joshua Demers’s Québexit, there’s now another entry in this nascent genre, and it’s an exciting, and very funny, one. Both My Internship and Québexit share an interest in the culture clash between anglophones, Québécois Francophones, and Indigenous people.

But Demers’s film takes the important next step of actually involving all three groups in the screenwriting process: he co-wrote the film with bilingual Québécois francophone actor Xavier Yuvens and Cree actress-director-writer Gail Maurice (recently seen on CBC’s Trickster as Georgina). The collaborative process really pays off because you feel like you’re getting an insider perspective on each of the characters, which ensures all of them are three-dimensional and the humour feels very, very specific. It also allows the film to be trilingual — in English, French, and Cree — which adds another level of authenticity and nuance.” Read the full interview.

Quebexit is streaming on Prime Video in Canada and the US. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

4. John Ware Reclaimed (Cheryl Foggo)

From the introduction to our interview with Cheryl Foggo: “It’s one of Canada’s best kept secrets that there’s a rich history of the Black diaspora in the Alberta prairies dating back over a century ago. What little is known about that history has been condensed in the popular consciousness to the story of cowboy John Ware, an enslaved American who moved to Canada and became a successful rancher. But even the historical accounts of him are limited to a single book, John Ware’s Cow Country by Grant MacEwan, published in 1960, written by a white man, and full of racist stereotypes about Black masculinity. Cheryl Foggo’s moving, enlightening, and appropriately infuriating new documentary, John Ware Reclaimed, attempts to reclaim not just John Ware’s story from the biased history books but the history of Black Canadians in the prairies.

Foggo replaces Grant MacEwan’s mythology of John Ware with a newer, more modern, and more nuanced take, which highlights both Ware’s humanity and the very real struggles he faced. She casts real life cowboy Fred Whitfield as John Ware, and together, they create iconic images of a cowboy in action in the gorgeous Alberta landscape. Through animation, Foggo grants us access to the love story between John Ware and his wife Mildred. The animated images depict the two always hanging onto each other, almost curled together, as if sheltering from the storm of the wider world. Through original country songs written by Foggo’s daughter, Miranda Martini, as well as songs by Corb Lund, Foggo further sets the tone for John Ware’s story.” Read the full interview.

John Ware Reclaimed is streaming free in Canada on the NFB website, and is available on VOD worldwide. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

3. No Ordinary Man (Aisling Chin-Yee, Chase Joynt)

From the introduction to our interview with Aisling Chin-Yee and Chase Joynt: “The story No Ordinary Man tells is one of lost transgender history that’s finally being reclaimed. The film’s subject is Billy Tipton, an influential jazz musician who worked between the 1930s and 1970s. It wasn’t until 1989, when Tipton died in the arms of his son, Billy Jr., that Tipton’s family and the public discovered that he was assigned female at birth. After his death, Tipton’s story was twisted: Tipton was unequivocally a trans man, but the cis-dominated media presented him as a woman who dressed as a man in order to get a foot in the door in the music industry. Even the most cited text about Tipton’s life, Suits Me: The Double Life of Billy Tipton by Dianne Middlebrook, framed his story around this harmful narrative.

In Aisling Chin-Yee and Chase Joynt’s hands, No Ordinary Man is no ordinary biographical documentary. They go way beyond the standard archival footage and talking head interview approach to tell Tipton’s story. Joynt explained that “understanding that there was no moving image footage of Tipton was both a restriction and an opportunity for us to immediately start thinking creatively beyond the bounds of reenactment and other ways that biopics tend to be created.” The film features photos and audio recordings of Tipton, as well as his music, and his life story is told through the words of talking-head experts, most of whom are trans. But another huge part of the film are “auditions” where the filmmakers invite a whole host of diverse transmasculine actors to act out and then dissect scripted scenes from Tipton’s life.” Read the full interview

No Ordinary Man is available on VOD in Canada and the US. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

2. Red Snow (Marie Clements)

One of the most inventive films of the year, Marie Clements’s Red Snow is part war film, part western, and part the story of the effects of colonialism. The magnetic and super talented Asivak Koostachin stars as Dylan, a Gwich’in soldier in the Canadian military who gets captured by the Taliban. This puts him in a bizarre position: he identifies as Canadian when he’s assumed as American, but as an Indigenous man, he doesn’t feel Canadian enough to be an asset worth rescuing for a ransom by the Canadian military. At the same time, as a soldier in Afghanistan, he’s somewhat serving as a force of colonisation whilst the Taliban is literally occupying the territory. This is rich territory for exploration, though in the early stages of the film, the dialogue often strays into cliche.

Still, the major achievement of Red Snow is the stunning visuals, which are paired with a non-linear narrative, which circles around memory, Gwich’in stories, and past romantic trauma. Working with cinematographers Robert Aschmann and Roger Vernon, and shooting entirely in Canada, Clements believably evokes the faraway places where the film is set. Though the film is particularly on point when in Dylan’s home territory, showing his connection to the land and snow. There’s a surreal, poetic quality to the storytelling, too, which feels more like Monkey Beach than any war movie I can think of, but then, this is Indigenous storytelling through and through. Despite its flaws, Red Snow is visually and intellectually inventive and is guaranteed to be unlike anything you’ve ever seen. AH

Red Snow is streaming free on CBC Gem in Canada and on Netflix in the US. It is still seeking international distribution. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

1. Kímmapiiyipitssini: The Meaning of Empathy (Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers)

From the introduction to our interview with Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers: “Kímmapiiyipitssini: The Meaning of Empathy opens on a herd of buffalo grazing against the gorgeous landscape of the Kainai First Nation in Alberta. As we watch a mother and child buffalo nuzzle against each other, the soundtrack mingles a gentle score with the sounds of a woman speaking to a newborn baby. Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers’s Kímmapiiyipitssini is a documentary about the opioid crisis ravaging Tailfeathers’s own community of the Kainai First Nation. It’s fitting that a film that approaches that topic with such empathy and humanism doesn’t begin with sensationalised imagery of harm, but images and sounds of parental love and caring.

In Tailfeathers’s own words, “Kímmapiiyipitssini is this Blackfoot teaching that we give empathy and kindness as a means for survival.” In keeping with this teaching, her film advocates for the controversial practice of “harm reduction” as a more humane and effective way to treat those who live with substance use disorder. As Tailfeathers explains in voiceover, the most common practice of treating addiction is preaching abstinence, perpetuated by guidance like twelve step programs. But that simply isn’t realistic for many people addicted to strong and deadly substances like fentanyl, which entered Tailfeathers’s community seven years ago and has since caused countless deaths by overdose. Harm reduction advocates that patients be provided an alternative drug that’s safer and easier to regulate, so that they can continue their daily lives without painful withdrawal symptoms.” Read the full interview.

Kímmapiiyipitssini: The Meaning of Empathy will be released to stream free on the NFB website in 2022, and will likely be available on VOD worldwide in 2022. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

Best Canadian films that world premiered in 2021

10. The Noise of Engines (Philippe Grégoire)

Based on writer-director Philippe Grégoire’s own experiences as a Canadian Customs officer, Noise of Engines is the story of a bored Customs officer who teaches firearms training, and who gets into scrapes when he has sex with one of his students.

Thrown out of his job on probation, he returns home to the small town where he grew up, only to discover his mother has filled his room with pillows on which his face is printed, and that he doesn’t really know what he wants to do with his life. He’s followed by incompetent police officers who think he must be responsible for a local sex crime because pornographic drawings have been found in which he is featured. And he meets an Icelandic woman who is in town for the car racing, with whom he forms a tentative friendship, bonding over their love of, ‘the noise of engines.’ The Noise of Engines doesn’t quite stick the landing, but it’s certainly one of the funniest films of the year, along with fellow Québécois film Saint-Narcisse, and it’s brutally incisive in its send-up of how doggedly following the rules and protocol can lead to very silly decisions. AH

Noise of Engines is still seeking distribution. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

9. Coextinction (Elena Jean, Gloria Pancrazi)

From our review: “Settler filmmakers Gloria Pancrazi and Elena Jean began the making of Coextinction as a fight to protect the Southern Resident killer whales, of which there are less than one hundred left. In the process of trying to understand what threatens the killer whales, they discover the dangers of the excessive noise produced by the shipping lanes, which interfere with the killer whales’ ability to find their prey. But soon, they realise the problem is not just with being able to find the prey, but the existence of the prey at all.” Read the full review.

Coextinction is still seeking distribution. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

8. Wochiigi lo: End of the Peace (Heather Hatch)

Haida filmmaker Heather Hatch’s Wochiigii lo: End of the Peace, which premiered at TIFF, though I caught it at Sudbury’s excellent CineFest, is a deep dive into the construction of the Site C hydro dam on the Peace River in British Columbia. From the beginnings of its development, it was clear that the dam would provide energy nobody needed, cost more money than it would ever earn back, and in the process, create major environmental destruction, especially through lands populated largely by Indigenous Peoples.

Hatch’s documentary charts the years-long fight, in courthouses and through protests on the ground, to stop the development of the dam. Hatch regularly cuts between the developments in the building project and Indigenous People’s ongoing fight to stop it, showing that destruction keeps happening even as the dam’s future is being debated. Hatch also connects this megaproject with a history of similar projects, like the Bennett Dam, which had major detrimental impacts on both the environment and Indigenous peoples. AH

Wochiigii lo is still seeking distribution. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

7. One of Ours (Yasmine Mathurin)

From our review: “The family at the centre of Yasmine Mathurin’s One of Ours is a maelstrom of complex dynamics governed by settler colonialism. Mathurin specifically follows Josiah Wilson, a Black twentysomething born in Haiti where he was adopted by a pair of Canadians — a white mother and an Indigenous father — who were living there at the time, and soon brought him home to Calgary in Canada. Having grown up as a member of the community of his father’s Heiltsuk Nation, Josiah is culturally and legally Indigenous. But as an adoptee, and a Black man, he looks like he’s out of place in this community. This also means he’s part of the African diaspora that was first torn from their homeland and brought to Haiti, hundreds of years ago, only to be once again torn away from his homeland by the Canadian family that adopted him.” Read the full review.

One of Ours will be streaming free on CBC Gem in Canada in mid-January 2022. It is still seeking international distribution. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

6. Night Raiders (Danis Goulet)

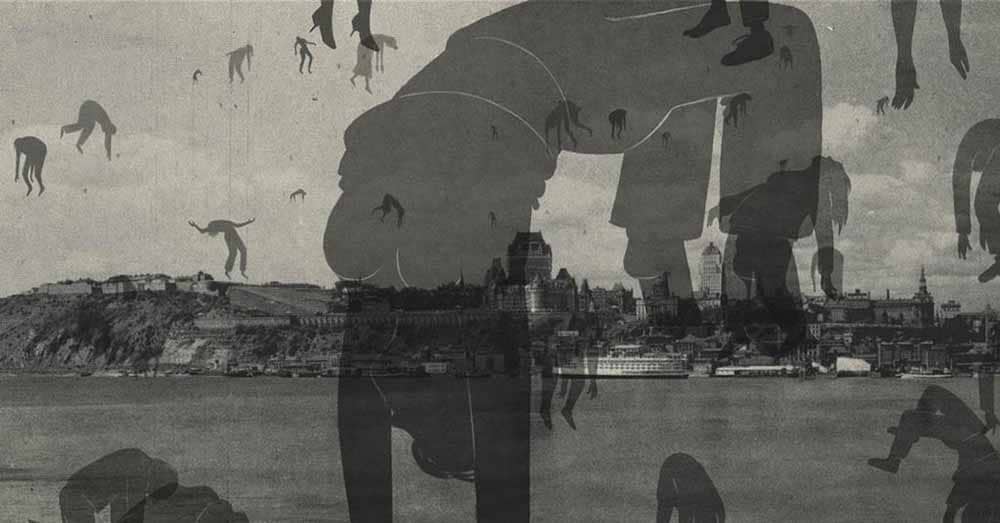

5. Archipelago (Félix Dufour-Laperrière)

From our review: “Québécois animator Félix Dufour-Laperrière makes his first foray into documentary filmmaking with Archipelago, which mixes archival footage with animation to tell the story of the land along the St. Lawrence River. Working from a documentary about the St. Lawrence from the 1940s, which itself is an inaccurate depiction of the region at the time, Dufour-Laperrière annotates, paints over, and plays with the footage, and in turn, our sense of the history of the land.” Read the full review.

Archipelago is still seeking international distribution but will likely be released in Quebec in 2022, and thus available on VOD in Canada in 2022. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

4. Bootlegger (Caroline Monnet)

3. Scarborough (Shasha Nakhai, Rich Williamson)

From our review: “One of TIFF’s most stirring crowdpleasers was Scarborough, a tough story with a huge heart. Catherine Hernandez adapts her own award-winning 2017 novel into the screenplay for this film about three kids and their parents living in Scarborough, a multicultural and low-income neighbourhood in Toronto. At a hefty 136-minute runtime, it’s a film that sometimes struggles to know what to cut from the source text. But it’s also easy to understand why: the filmmakers’ love for their characters is so palpable, it’s infectious. When the film ended, I, too, wished I could keep spending time with them.” Read the full review.

Scarborough will be released in Canada in early 2022. It is still seeking international distribution. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

2. Run Woman Run (Zoe Leigh Hopkins)

From our review: “On a shoestring budget, Zoe Leigh Hopkins has crafted a feel good film about learning to care for yourself in the wake of tragedy and trauma. Set in the Six Nations in Ontario, Beck (Dakota Ray Hebert) is a thirtysomething single mother who lives with her father and shares a bedroom with her pre-pubescent son, Eric (Sladen Peltier). When she gets diagnosed with diabetes, she has enormous trouble making lifestyle changes (taking medication, improving her diet, and starting to exercise) because she’s gotten so used to putting herself last, ever since her mother died by suicide, and there was her father (Lorne Cardinal), sister, and son to care for.” Read the full review.

Run Woman Run will be released in Canada in early 2022. It is still seeking international distribution. Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on its availability.

1. Kímmapiiyipitssini: The Meaning of Empathy (Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers)

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch great Canadian films at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.