After the film’s world premiere at Sundance, Sam Green discusses his live documentary 32 Sounds, encouraging active listening, and the possibilities in the live documentary form.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

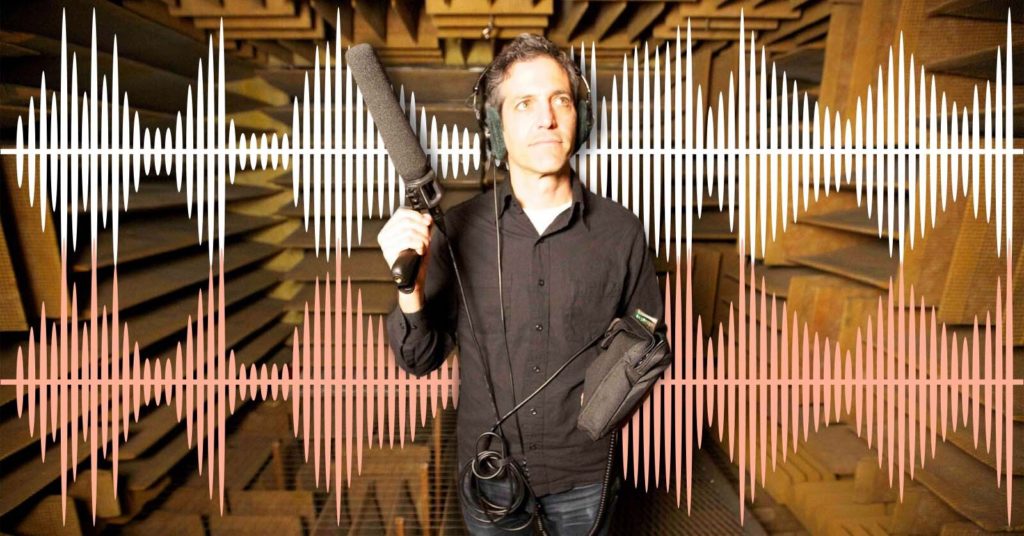

Director Sam Green has made a career out of pushing the boundaries of documentary filmmaking making what he describes as “live documentaries”. These are part locked footage, part live performance. I first became aware of his work when I saw the 2012 world premiere of The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller in San Francisco, which was unlike anything I’d ever seen before. While archival footage of the great inventor-thinker-innovator played on screen, Green delivered live narration. The band Yo La Tengo also performed a live score.

Director-editor Joe Bini, whom we interviewed about live documentary in our ebook Subjective realities: The art of creative nonfiction, also saw the film in SF. This led to Bini and Green collaborating on the Kronos Quartet live documentary A Thousand Thoughts (2018). Despite his more experimental recent work, Green is perhaps best known for his Oscar-nominated documentary The Weather Underground (2002). It has since even been adapted into a dance performance.

How 32 Sounds innovates in the live documentary space

Green’s newest live documentary, 32 Sounds, is an exploration of the many ways we engage with sound, especially emotionally. It world premiered virtually at Sundance in January and will be rolling out to venues around the world this year. Unlike Green’s previous work, the film is designed for both an at home audience wearing headphones, and a live audience. Live audiences wexperience live narration and live music performed by singer-guitarist JD Samson. Just as musicians record albums and still play live shows, 32 Sounds creates complementary experiences for both live and at home audiences.

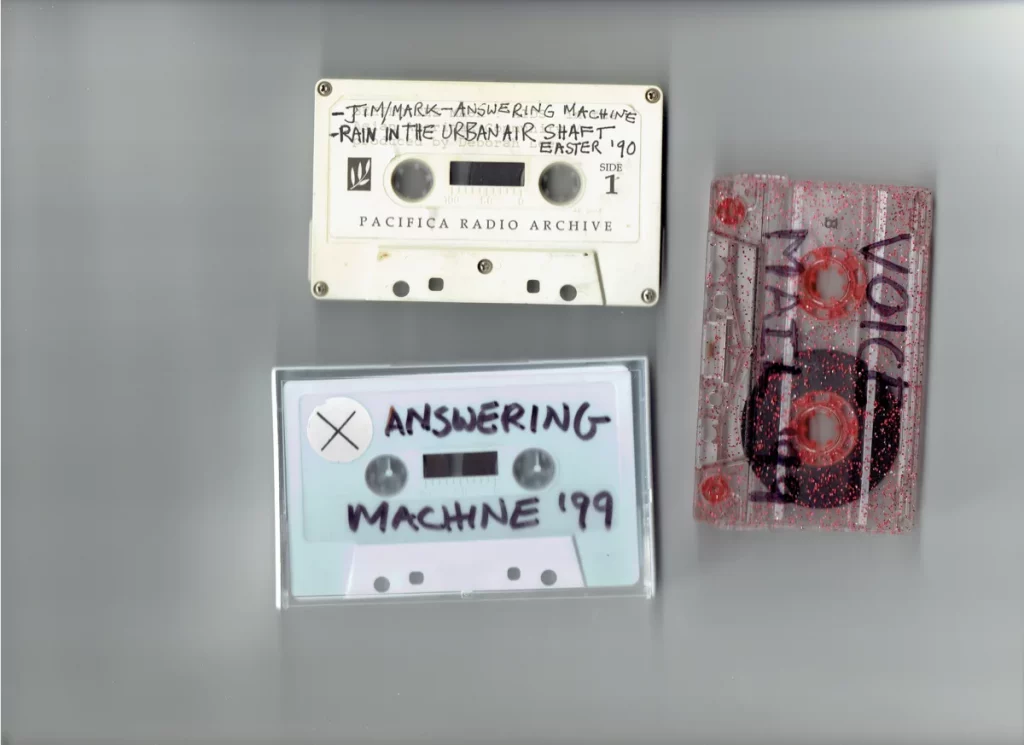

On the Seventh Row podcast, Orla Smith described 32 Sounds as the “feel good film of the festival”. It’s an immersive deep-dive into how sound makes us feel and how we process sounds. It asks us to consider the sounds we encounter all the time and don’t notice, the sounds that mark our memories, and how we create sound. Its vignette structure was loosely inspired by 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould (François Girard, 1993). 32 Sounds certainly contains more than thirty-two sounds, though the selected ones are occasionally tallied for us. It is alternately lighthearted — explaining sound waves with a whoopie cushion — and deeply contemplative, as when Green dreads listening to the answering machine recordings left by his late brother.

Introducing us to the film

32 Sounds opens rather unconventionally with Green and Samson welcoming us to the film. It’s like an introduction at a film festival premiere, only this one has been recorded for perpetuity. They explain that this isn’t a regular documentary, and instruct audience members to go get their headphones. If, like me, you were obstinate, they remind you again later. They’re sitting next to a binaural microphone, which looks like a dummy head with microphones in both ears. Binaural microphones record sound as we, as humans, really hear it. You only hear the effect of it with headphones, hence the plea. A binaural microphone records the sound of a hockey puck being hit, allowing us to feel its movement through space. From the start, Green establishes how the film plays with sound and asks us to listen actively. As Orla puts it, the film talks back to you.

We see what’s making sounds — a cat purring, a man blasting “In the Air Tonight” from his car — and the microphone recording them. This allows us to place the sounds visually and aurally in space. We think about the sound of silence: interview subjects sit awkwardly in front of the camera as Green collects the sound of the room, room tone. We meet experimental composer Annea Lockwood who has been recording sounds every day of her life. She talks about “listening with” a landscape — as a way of engaging with it — rather than “listening to” a space. Visually, Green repeatedly places us in nature and other spaces to get acquainted with the sound of the space.

An exercise in active listening

32 Sounds is an exercise in active listening. Green finds new ways to keep us engaged, to get us focusing on the sound. This prevents the film from becoming an avant garde experimental film that’s just a series of sounds in a montage. Sometimes, we watch other people listening to sounds. A woman at the British Library’s sound archive listens to one of the two last living moho braccatus birds. Other times, Green asks us to close our eyes to get a sense of a sound. Sometimes, we just see the microphone recording the sound. At one point, Green invites us to get up and move around to the music for a dance break.

Sometimes, we’re reminded of how sound is something that our brains have to process. An annotated educational video about how the brain processes sound waves leads into one of the highlights of the film: using the binaural microphone. One of Green’s subjects walks around the binaural microphone with a box of matches. We’re suddenly aware of our brains processing the sound and thus allowing us to feel, spatially, where the man is. When he blows into the ear of the microphone, it’s as if he’s blowing into our ears. The same pressure wave is being produced through our headphones, and we suddenly feel like we’re right there.

It feels like an amazing special effect, and yet, it’s just how our brain naturally processes sound. We just aren’t used to having recorded sound reproduced in a non-artificial way. Green takes us into the studios where sound is manufactured. He reminds us that movie sound, and surround sound, are inherently artificial in a way the binaural microphone recordings aren’t.

A densely-packed essay film

Edited by Nels Bangerter (Cameraperson, The Hottest August), 32 Sounds is a densely-packed essay film that delivers a unique experience. It introduces us to a cast of characters who are passionate about sounds. It invites us to listen to the fog horns of San Francisco with the same reverence as a meaningful piece of music. And it reminds us how much sound affects us. For Lockwood, for example, who lost her partner recently, listening to music is too intense. It brings back memories of when the two of them together would listen to the same pieces.

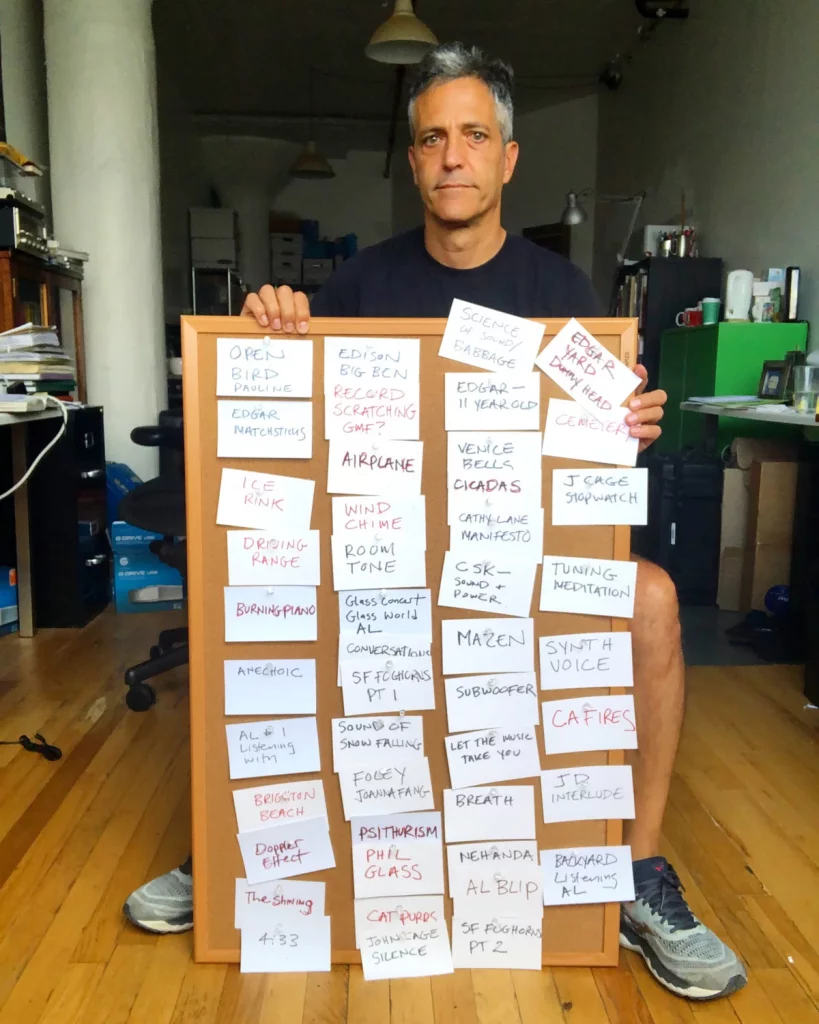

After the virtual world premiere of 32 Sounds at Sundance, I sat down with Sam Green via Zoom. We talked about “live documentary” as a form and how it borrows from other genres. Green also discussed curating the eponymous thirty-two sounds, finding a structure for the film, and more.

7R: It seems like 32 Sounds has, in some form, been gestating for a long time, because it includes footage that you filmed twenty years ago. What’s the story behind how this project came about?

Sam Green: When you’ve just finished a film, you’re not quite polished at talking about it yet. Where did this movie come from? I’ve got to come up with a very pithy answer, but I don’t have it yet. I think, in general, I have a film, and then it leads to the next one.

The last movie I made was a live cinema [documentary] piece with the Kronos Quartet [A Thousand Thoughts, co-directed by Joe Bini]. We were supposed to do it in Toronto on the 18th, but it got cancelled. [It’s been rescheduled for December.] I thought a lot about listening and sound in that movie. Because I really wanted people to listen to the music and feel the music.

Normally, we think of movies as a visual medium, and they are, to an extent. The sound is always seen as a second-class citizen. Music documentaries, especially, are almost always a story about the group with little bits and pieces of music to illustrate. You rarely get to fully hear and feel the music in a music documentary, ironically.

Figuring out how to get people to listen

So, I was really trying to figure out how to get people to listen. With film now, there’s so much wonderful sound design. Even the most terrible Hollywood movie has spent millions of dollars on sound design. You never have to work with your ears; it just washes over you. People watch movies and listen in a very passive way. It made me think a lot. That film somehow — and a lot of this was Joe Bini — kind of just magically works. It’s hard to know how it works, but people feel it; it just works in a kind of explosive way.

Maybe five minutes into [A Thousand Thoughts], I say to everybody, “Let’s just listen to the sound of the room for thirty seconds.” The lights go up a little, and John Cage is on the screen. I say, “Listen to the sound of the fans and the people shifting in their seats.”

I know this is weird, because normally, in a movie, you try to tune all that out. But this is not a normal movie. Let’s think of this as tuning up our ears. It’s thirty seconds. It’s a little awkward, but that moment of, “Ah, I hear a projector, I hear a fan,” or this moment where suddenly your ears are engaged in a different way, got me curious about how to get people to listen in a powerful way. That was really the genesis of it.

Getting inspired by Annea Lockwood

There were a couple of other things; early on in the pandemic, all my screenings were cancelled, and I suddenly had a lot of time. I’d started this movie about sound, and so I was like, I’m just gonna get a huge stack of books and read a lot. I read a book about a composer named Pauline Oliveros. And it mentioned somebody named Annea Lockwood, who I’d never heard of: it said she recorded the sound of rivers for fifty years, and I was totally intrigued. I just Googled her, found an email, wrote to her and said, “Could we talk on Skype?” She wrote back immediately to say, “Sure!” So, we sort of became pandemic friends, and I found her such a wonderful muse. That’s why she’s so central to the film.

Learn more about sound design with our interviews

We’ve interviewed many sound designers who’ve worked with filmmakers including Joanna Hogg, Lynne Ramsay, and Kelly Reichardt.

7R: In 32 Sounds, you say that you are somewhat inspired by 32 Short Films about Glenn Gould, which is a big deal here in Canada, but I never hear it talked about elsewhere, so that was exciting.

Sam Green: I love that film. When you make a film about sound, you sort of have to have some kind of organising principle. That’s one of my all-time favourite movies, and it’s funny because the biopic is one of my least favourite genres. Biopics are so predictable and boring; there’s so many tropes. Like the Johnny Cash biopic [Walk the Line], which actually was pretty good, but it starts with the scene, then it flashes back to tell the whole story, and then ends up back on that scene, and it’s like “Oh, God.”

The thing I love about 32 Short Films is it takes a life which is so weird and complicated — anybody’s life is weird and complicated — and resists narrative. It’s a portrait in bits and pieces, which I think is so sophisticated, smart, and real. I just loved it. There’s no way to make an objective film about sound; all you can do is approach it in bits and pieces.

One last thing about 32 Short Films about Glenn Gould that I loved is that there’s such a variety of modalities; there’s the animation one, and sometimes there’s interviews, and sometimes there’s dramatic re-enactments. It always keeps you guessing, which is so rare in a movie, to be surprised.

7R: When I saw the binaural microphone at the beginning of 32 Sounds, I thought, “it’s just like The Encounter.” And then you talked about seeing a Broadway show that used a binaural microphone, and I thought, “Oh, he saw The Encounter!”

Sam Green: The Encounter was amazing. I remember that moment when he talks into the dummy head, and it was just like, woah! It’s funny, because later I was thinking, “What was the story about?” In some ways, it made no sense: the story had no connection to the binaural effect, which was what was dazzling about it. Even though the play was great, and he’s [Simon McBurney who also directed the show] an awesome actor, the binaural effect is what really stuck with me.

7R: How did you figure out what sounds you wanted to use, and how to illuminate them in 32 Sounds? Do you just amass a large collection and then try and make sense of it?

Sam Green: One of the things I always loved about filmmaking is that you have an idea, and you have material, and you try to marshal the material into that idea, and the material says, “I kind of get what you’re saying, but really more like this.” It’s a dialogue between you and the material and the world.

I had such a long list of sounds that resonated with me for one reason or another. That’s how I started. There were tons of different ones that came and went in the editing. For a long time, I had my early thought that this would just be almost a structuralist film, where there was no explanation: it would just be a series of sounds and stories around them. I put that together, and after forty-five minutes, it would fall apart. People would be like, “I don’t get it… it’s too long… it’s getting repetitive.” We call that the forty-five minute problem: it couldn’t hold together as a film.

This movie was hard to make. It’s almost like that cliche of a sculptor who allows the sculpture to come out of the stone, which sounds corny, but there’s something to it. As you work the material, you start to realise why you’re drawn to this, and what it is that is getting to you. That takes a lot of time and struggle.

7R: We were talking before about how you get people to really listen. I thought a lot about that during the film. While watching, I was aware of my brain processing sound, which is not something I think about often. I watch movies and think, “I like how the sound is here,” but I don’t think, “Oh, it’s near my ear!” There are activities placed throughout the film to bring you back into listening more actively, which is a neat idea.

Sam Green: With some of my early cuts, there were two ways to make this film. I could have made a very structuralist film that was mostly just listening, and that would be interesting, but I think it’d be very experimental, like a James Benning film where half the people [in the audience] would walk out. And if you really wanted to do that, you could do that. And then another version of this was tons of me talking about why the sounds are significant or meaningful, and very little listening.

So, my early cuts were like that, where [it feels like], “You [should] just shut up and let us listen more.” Finding a balance and allowing the film to open up, but still having it hold together as a kind of narrative, was the huge challenge with it.

There are certain sections where it’s the foghorns, the cicadas, and wind chimes; it’s maybe three minutes of nothing but sound. I hoped, with a repeating rhythm of those interludes, to get people back to just listening, because a lot of [the film] is me talking, which, frankly, is a different kind of listening. When you’re listening to somebody talk, it’s different than if you’re just listening to sounds.

7R: Tell me about how you conceived of the opening of 32 Sounds. You literally say, “This is a different kind of documentary,” and repeatedly insist that people get their headphones.

Sam Green: This is totally bizarre. We have this [live version of the film] where I’m on stage and JD’s on stage, and everybody in the audience has headphones: we travel with 500 sets of headphones. That was the way to really make sure everybody has the same experience. When you’re doing something virtually, which I was happy to do with Sundance — if they were pivoting, I would pivot, there’s no question about it. But, people are listening in weird ways. Often, it’s three people sitting on a couch: they’re not going to wear headphones.

But with the binaural stuff, you don’t get [the same experience]. You don’t get the hockey player hitting the puck, and you hear it over there. So, it’s still a good experience, but it’s not the same experience. You’ve got to really try to get people to do it, but I have no idea who did.

7R: I did, but it took me until the second reminder to get it. Because I was like, “I know how a binaural mic works, I get it” and then I was like, “Oh, they’re actually going to use this a lot.”

Sam Green: It worked! That intro was something we filmed, like, a week ago, just when we knew it was going to be virtual. We had to do something to start it out. You see us, and I think that injects a different tone. If it just starts in this removed, cold way, and you never see us, there’s something much more impersonal about it. With the films I make, I try to make them almost conversational, or at least, I think the live form lends itself to, “I’m talking to you, and we’re sitting in the same room together.” There’s something humble, and human, and generous about it, I hope.

7R: Live documentary is very interesting as a form because it’s sort of like, is it theatre? Is it film? It’s kind of both.

Sam Green: I first made a live [documentary] cinema piece in 2010. It was at Sundance, and I thought, sort of like the Yo Lo Tengo Buckminster Fuller film, “Well, what do you do with a live documentary? I’ll do the show, and that’ll be it.” We ended up travelling all over the world and showing it, and it was really fun.

There are all these different worlds that are right next to the film world, but very separate. The performing arts world is a very different world with its own customs and its own budget and financial models.

I realised, “There are different terms for this form.” It’s the exact same form. In the performing arts world, there’s a term called lecture-performance, which is basically what I’m doing, a fancy lecture performance. But in that world, I would sometimes let people call it a performance, and I’m fine with that in that world. We did some shows in libraries, and I’m all for that, but I would just say it’s a fancy PowerPoint presentation, and that’s what worked in that world.

But for me, because I’m in the film world, I see this as pushing the film form. So, I’ve always wanted to keep ‘documentary’ in the name of this form, just so that people know this is a film, even though it seems weird, and it could be considered other things. I think of it as a film, and it’s in dialogue with the film form and film history.

Learn more about live documentary with the ebook Subjective realities

We talk to Sam Green’s collaborator Joe Bini, as well as Zia Anger, about their work in live documentary.

7R: I would guess though that you do take some inspiration from some of those other formats for live documentary.

Sam Green: For sure. My partner’s a choreographer, so I learned a lot about performing arts through her. But also, an early experience for me is I made this film about The Weather Underground [The Weather Underground, 2002] many years ago. A couple of years after I’d made it, I was sitting there doing email, and my partner was next to me or something, and I said, “I gotta delete this email from a choreographer. He’s writing about The Weather Underground or something.” And she said, “Well, let me see it.”

He had written to me a bunch of times, and I just kept deleting it, and she said, “Oh, that’s this guy, David Dorfman. He’s a real person. You should talk to him.” And I said, “Well, it sounds so dumb to make a dance piece about The Weather Underground. I worked so hard to get the facts in the historical context, a dance couldn’t do any of that.”

I talked to him, and he ended up making this dance piece about The Weather Underground, which I saw at Yerba Buena in San Francisco. It was amazing. There were no facts and no historical context, but just through light, music, mood, and movement, it was deeply moving. That opened my eyes a lot to how, with different forms, people bring different expectations. So that really interested me: to play with people’s expectations through playing with form.

7R: What do you feel you can get in live documentary from combining film with this live component that doesn’t exist elsewhere?

Sam Green: Most importantly, I think, is that people have no preconceived notions: they’re like a blank slate. When you make a traditional music documentary, for example, if you had somebody’s music playing for three minutes, it would be weird and experimental, and you would instantly be in the weird experimental movie world: people’s expectations of the form are very rigid. If you do something a little differently, you’re avant-garde, and nobody’s going to see it.

One of the things I’ve loved about live documentary is that since nobody’s seen anything, whatever, they’re game! With the Kronos Quartet, I made these pieces where they’ll play for three minutes, and people sit through it, and you’re not like, “Oh my god, this is a long music break.” It’s using the most powerful tools of cinema: huge images and sound that washes over you to their fullest.

You go to a super fancy restaurant, and they make you this amazing meal, and then you go out to your car, and eat it in the car. That’s sometimes how it feels for people to make an amazing movie, and you watch it on a laptop at home while you’re doing your emails. I do feel like it’s kind of using the magic and the power of cinema to its fullest. People turn off their phones. You buy a ticket; it’s much more meaningful. When people spend thirty bucks, they are there. So anyway, that’s a little bit of my rant.

7R: Your other live documentary films, as far as I’m aware, you can’t just watch at home; you have to go to a performance. On the Sundance website, it says 32 Sounds is a live documentary that is designed as a live experience, but also an at-home experience. Are you going to let people watch it at home after Sundance?

Sam Green: Well, this is the first live cinema piece I have made where it feels like it also could exist [at home]. The piece I made about the Kronos Quartet, a big part of why that’s a powerful piece is [the Kronos Quartet are] sitting right there. If it’s just a recording of it, it’s about half as good.

In 32 Sounds, me and JD are less central to it. I don’t know if what we showed last night [to a live virtual audience at Sundance] is as strong as the last [live show] I’ve experienced, but it certainly works as a film. I’m a control freak, in some ways, so part of doing live stuff is you can control people’s experiences.

By doing a live version we know people are going to wear headphones. We know they’re not going to be reading their email, and you can make people have a strong experience. Whereas, if something’s streaming or [watched] on [a] TV, you just never know. Over the years of making live cinema, it pains me a little when people say, “I’ve never seen that” or “I’ve never been able to see any of your stuff,” but it’s a trade-off.

7R: When you make a film, you can edit every second, and then you have controlled the experience to the millisecond. But presumably, when you’re planning to do a live documentary on stage, you have to leave some space for yourself, because it’ll be different tonight versus the way it is in a week, or if you do it in Toronto versus in Tokyo.

Sam Green: When you make a film, you are so rigorous, down to the frame that you’re editing. Then, you turn it over to people who can watch it in any way they want, and have their own experience with it. There’s an irony there. What we’re doing is a little looser, in a way: if music starts two seconds late [it’s okay], [because] there’s a lot of flow and a lot of looseness. It’s like playing music: even the Kronos Quartet plays things differently every night.

7R: How did you think about the sound design for 32 Sounds? Obviously, there are parts of the film where you have the binaural microphone, and you’re really spotlighting how you use it. But then, you’ve also got other recordings from way back, which obviously weren’t designed with the binaural microphone. Are you doing things in the sound mixing to change it? Then, there’s the element of how people are going to be watching it… did you make changes, because you’re going to be doing this virtually?

Sam Green: One thing that really struck me with The Encounter is that it uses this binaural technology. I say this in the film: film has not been able to incorporate any of this, even though VR and gaming has, because nobody can figure out how. It doesn’t work very well with speakers, and making a movie where people have to wear headphones is sort of weird. Film, especially documentary film, is so primitive in terms of sound technology, it’s really weird. It’s embarrassing in a way that we, as a form, have not evolved from the 70s.

7R: And even then, it was decades behind music.

Sam Green: Totally. So I’m like, “Why isn’t anybody else doing this?”, figuring out a way to take some of that and bring it to film. Because even documentary sound people, when you talk to them, they barely know how to do stereo recordings. I had to find a VR person [to do the sound for the film]. [Laura Cunningham] also studied architectural acoustics at RPI University, so she’s smart about sound. Not all documentary sound people are.

Thinking about sound design is interesting. We have different mixes, I worked with Mark Mangini, who just did the sound design for Dune, and I thought, “What?!” I saw that in an Atmos theatre, which was like being pummelled with sound. I laughed with him, and said, “Mark, this is gonna be the tiniest movie compared to Dune.” But we have different mixes. There’s a mix we did for last night, with most people wearing normal headphones, and then we have a mix for the live show that we have our own headphones that we mixed for.

In that dance section [where we play dance music and invite people to dance while they watch], it’s about low sound and vibrations. We put these huge subwoofers on the stage and just blast people with this low sound: you can feel it, it’s totally weird. And during that dance interlude, what I say in a live show is you can get up and come down and put your hands on the subwoofers, and in an intense way, you can feel sound. We have many different kinds of sound approaches for forms that the film will take.

7R: One of the coolest parts was that sequence with the rocket scientist, where he’s walking around the binaural microphone with the matches, and the part where he actually blows in your ear. That was so cool, because you can feel the pressure change from the mic in your headphones.

Sam Green: Yeah, that stuff is really cool. It’s funny, because it’s just the way we normally hear things: who knew it could be that striking? But it just shows how unrealistic all these portrayals of sound we experience are: when something’s realistic, it blows your mind. It’s like they were next to me, just like a normal person would be next to me!

7R: When I was sitting at home watching 32 Sounds with my headphones, I felt like that was the first time I’ve watched a film at home that felt designed for that experience. Most movies are mixed for the theatre. Maybe they mix them again for home, but maybe they don’t really pay that much attention to it. Lots of people watch it at home, and they don’t have a stereo connected to their television, and they’re watching on TV speakers or on their computer. But this film is designed for the home experience.

Sam Green: I’m interested in that. It was weird, because that show last night was thrilling. Everybody is at home, but we’re also in this virtual theatre. That added a wrinkle of oddness to it. I really like the form of making a movie that’s just for a person. In some ways, it’s like the podcast model, which is a cool and intimate way to connect to things. I think people like that. There’s something very powerful about somebody talking directly to you. I think there’s a real opportunity for film to not pretend to be for the theatrical experience and to acknowledge that it can just be the filmmaker, the film, and one person having an experience together. I think that’s really powerful.

7R: How did you think about what images to pair with the sound? In 32 Sounds, you talk about how you figure out what to show, and then for example there’s the cat making a sound, and we see it from far away, and then we get close up. We get the image that correlates with the sound, but we also see where the microphone is.

Sam Green: I think the challenge with making a film about sound, or with sound at the forefront, is that it’s really easy for your eyes to take over. You have to be very judicious about what you show, and not give people too much to see if you want them to listen.

That first scene with the bird, the moho braccatus, was one of the first moments where you really want people to listen and sit with a sound. I experimented a lot with different ways to edit that. A lot of it is just nothing, a blue screen, but how to get into that? I made many versions of that where it didn’t really work. People weren’t very engaged with their ears. At some point, I put in a shot right at the end of the scene where the woman, Cheryl Tipp, is listening. Seeing her face listen, that worked. It was a real epiphany for me. I realised, if you show people listening, it does something to a viewer. It makes sense; it’s not a surprise. That’s a trigger for people to actually listen, as well, themselves. That was a real breakthrough.

7R: How did you think about when and how to use that binaural microphone in 32 Sounds?

Sam Green: Over time, I realised there are certain ways in which binaural sound is powerful, and a lot of ways it’s not. It became clear that you have to have something in space that’s very identifiable for it to work. Like the hockey player who hits the puck, and then it bangs off a wall over on the left, that really works: we can hear that. Whereas if you just do the sound of a crowd or something that’s very diffuse, you can’t really tell the difference. The “In the Air Tonight” guy [who drives around NYC blasting the song from his car], it’s not really a binaural thing you’re getting from that: it’s just loud. [There are] different sounds as it bounces off the apartment buildings, but it’s not spatial, necessarily.

7R: Did you carry that binaural around everywhere?

Sam Green: No, it’s really expensive to rent. From time to time, we would realise we need another binaural scene and would think, “What would be good? Let’s do the Zamboni. That seems like a good one.” So we did a shoot with that. I did a number of different shoots, but we didn’t take it everywhere. It’s not easy to work with.

7R: The key scenes with the binaural mic in 32 Sounds seem to be the one with the matchbox, and then JD playing the guitar.

Sam Green: And whispering and goofing around in the beginning, too. With the JD music scene… in a normal movie, the music is always unacknowledged; it is just kind of there, but nobody ever says, “and here’s the score.” It’s like an invisible and unacknowledged part of the film, and it just seemed crazy if this is about sound to have all this music and not say anything or acknowledge it.

I wanted to do something with JD that would be about music and about her playing music, so that idea just came up. I love that song and its several parts. In the live version of that, she’s on screen, playing two parts, and down on the stage, playing another part. It’s a sort of a weirdly interactive duet.

7R: How did you think about how to use music in 32 Sounds?

Sam Green: I love working with JD. I love JD’s music. In a way, the film can only take so much music because music distracts from sounds, or music can fight the sounds. So, it was hard. At some point, JD said, “I’m not even playing much!” But music, on the other hand, is really powerful for creating an emotional experience. So [we were] trying to figure out where and how much music to put in, but not step on the sounds or get in the way of the sound. There’s still probably people who think there’s too much music and it got in the way of the sounds. But I like music, and I don’t mind.

At some point when I was making the Kronos Quartet movie with Joe Bini, somebody said, “There’s too much music.” Joe said this quote that I love that always stuck with me: “Fuck that person. This is opera.” I was like, “Yeah, Joe, this is opera!”. If you’re thinking about it as opera, way too much music is great. Joe is awesome. He’s a magician. His stuff is awesome, because Joe is such a good writer.

7R: Can you tell me a bit about the editing process for 32 Sounds? Do you have a lot of people come in to see how they’re reacting to the film?

Sam Green: I really depend on people’s feedback. I edited for about a year, and then I couldn’t do it myself. It’s just too hard for me to edit alone. I worked with Nels Bangerter since August, so that’d be about five months. Have you ever seen Cameraperson [Kirsten Johnston]? He edited that, and he edited The Hottest August. Those were movies I love, in general, but I love them both formally because neither of them was a plot movie or a character movie. They were sort of modular films that somehow held together, and that’s what I wanted to do. I figured Nels was good at doing that, so we worked together, and that was huge.

Some movies you can edit yourself if there’s a narrative to hang it on, or something to work with, sort of like the wind at your back. But this movie was so hard because you could make any order. I needed somebody else to help shape it, and Nels pushed it in a more personal direction, which was hard for me. I’m squeamish about personal films. I couldn’t have done it without him. So then, we worked together for five months and wrapped up recently.

7R: Have you performed the live documentary 32 Sounds in person?

Sam Green: We did one [work-in-progress] show at MASS MoCA. We did a two-week residency where Nels and I edited it on Premiere on a computer thinking like, “This scene, I’ll stand here,” and imagining what it would be like as a live piece. And at MASS MoCA, we spent two weeks doing that, figuring out how it could work with lights and sound as a live performance.

At the end of that, we did a show for a couple of hundred people, which was super interesting, because you don’t know how things will work. That dance scene, for example, is long. It’s about four minutes long. A lot of people, when I showed them a video of that dancing, said it goes on way too long. We had no idea what was gonna happen. At MASS MoCA, people got up and moved around and danced. It was like a dance party. It was great. That’s one of those things where you never know until you have an audience how things are going to work. That’s the only show we’ve done.

7R: Do you go back and edit your live documentary films after you’ve done performances to tweak them, or do you just tweak the live component?

Sam Green: Well, both. I have gone back and changed things, especially if I’m thinking, oh, this intro doesn’t really work the way I thought it would. It’s hard, though, to go back in and edit because we already did a colour correction and sound mix. But you want the thing to work. If necessary, we’ll do that.

7R: Could you tell me a bit more about how you get commissioned to do 32 Sounds? I saw that Stanford Live was involved, and they do some cool stuff. Documentary funding can be a challenge regardless, and if you’re not making an “issue film,” it is harder to get it funded. I know from personal experience, once you work in anything interdisciplinary, people don’t know where to put you. But it seems like working in live documentary opens up new possibilities for funding.

Sam Green: Well, that’s the super interesting thing. I realised, there’s the performing arts world, and there’s the documentary film world. The performing arts world is an odd world. The documentary film world has been completely transformed by digital. Everything has changed: the distribution landscape, the funding landscape, all of it is radically different now than it was even ten years ago, or twenty years ago.

The performing arts world is this weird world where it’s pretty unchanged, because there was no digital commodity to change everything. It’s pretty much the same as it’s been for many years. In that world, the way work gets made is that presenters, often university presenters, have a lot of money and they put money into projects, and then those presenters get the premiere or the first shows. We’re going next month to Stanford to do a show, and then NYU Abu Dhabi to do a show — all these places that gave us money to help make the film.

Alternative funding for boundary-pushing films

I totally appreciate that world. Those presenters look out for the artists that make the work, thinking, “If we don’t help these artists make work, we’re not gonna have anything to show.” The documentary film world is like, ah fuck it, show up when your film’s done: if you can’t make it somebody else will. I appreciate the performing arts world because it’s, in some ways, like a pre-market capitalism world, or a slightly socialist world, which is awesome.

For this project, we also got money from impact partners, which is like, the new paradigm in the documentary world: people investing in a film and hoping to make money back.

7R: The composer Annea Lockwood talks about the idea of “listening with” an environment versus “listening to” a place. How did you take that on board for 32 Sounds?

Sam Green: I love Lockwood. She’s so inspiring. She’s so smart about sound. And that’s her idea. It’s a semantic distinction that evokes a very powerful, almost cosmological or epistemological, distinction. If everybody in the world thought more about listening with, we probably would not have a lot of the problems we have now.

Annea Lockwood’s not somebody who’s on a soapbox, but I do think that that’s a powerful idea. I’m very inspired by her: even just how she’s navigated the world, having a career and making work that’s meaningful her whole life, and also dealing with loss and grief, and having a joyful, positive, full-hearted approach to life.

In a way, [“listening with” is an idea that] the guy with the foghorn [talks about, too]: he uses the foghorns to feel that connection with the ships on the sea, and the tides, and a big sense of life — all the little bits and pieces of beings and non-beings who are out there that make up a web of our existence. You get sort of woowoo at a certain point, but it’s a real thing that I appreciate. Those are two old people, and it feels to me like old people somehow have a clearer sense of that than maybe younger people do.

Sound evokes space

Sound more than any other sense evokes space, and is situated in space, and places us in a space. There’s that shot at a certain point towards the end of the bat flying in slow motion, getting a moth, and it’s totally amazing! Bats are blind: they’re doing that all through echolocation. It’s, in some ways, an exaggerated form of what we do: situating ourselves in the world and in time, through sound.

Sound is sort of like sex in that it’s profound and deep, and it’s hard to talk about in any way that’s not corny or cliche. The language of sound is like, “Music unifies everybody. It’s the universal language,” or “sound is mysterious.” There’s a lot of corny ways of thinking about sound. There’s not a lot of sophisticated, yet powerful or insightful ways of thinking and talking about sound.

But I think Annea Lockwood is [sophisticated in her way of talking about sound]. Christine Sun Kim is, too. I saw a TED talk [Kim] gave, and she talked about the idea that sound is so much more than just sound: it’s all these social relations, and it’s powered social currency. All these things we, as hearing people, don’t notice, because we’re going with the current. That rocked me. I’d never thought about sound like that. What I tried to do is talk about sound in different ways that are not corny and not clunky and dumb.

7R: There are a few points in 32 Sounds, where you ask people to close their eyes and listen. But there’s text on the screen that says that if you’re deaf or hard of hearing, then you should keep watching the captions. How much did you think about how to design the experience for deaf and hard of hearing audiences?

Sam Green: If you have Christine Sum Kim in your film, you have to make it accessible. It’s a challenge. At Sundance, there was a captioned version, and an audio-described version, as well.

The captioned version has all these conceptual challenges to it. In the section with the cicadas, for example, it says, “The sound of cicadas buzzing.” If somebody was born deaf, is that meaningful? But then, if you don’t do that, how do you describe a sound? It’s really hard to think about.

There are a lot of different ways in which captions have to work. And for people who are hard of hearing, or were hearing and can no longer hear, it’s easier.

But how do you describe sounds for people who are deaf? And born deaf? It’s a really good question, and I don’t know. But we’re pretty committed to making something that’s meaningful to many different kinds of perceptual abilities and backgrounds and perspectives.

7R: When you perform 32 Sounds live, do you have captions?

Sam Green: The way opera is subtitled, there’s captions. If you’re blind, there’s a headset that will have the audio description track in addition to the soundtrack, and the audio description is probably just little bits of narration from a person who tells what’s happening visually.

7R: You mentioned before that working with an editor was super important for personal material. Obviously, you have very personal material in 32 Sounds, so how did you navigate that?

Sam Green: That was one of the biggest challenges. There’s so many ways to go wrong with a personal film. I’ve seen many personal films that make me cringe — the filmmaker comes off as self-absorbed, or narcissistic, or just boring. I don’t feel like I’m more interesting than anybody else. Every single person, I think, is fascinating, on some level, but not always enough to make a film about.

I was trying to put in enough personal stuff to hold the film together, but not too much. Some people told me there’s not enough. You never know what the balance is. While we were making this film, I was constantly thinking to myself, “This is such a weird form.” It’s about an idea, and it’s portraits or scenes, and there’s narration, and it’s slightly personal, but it’s not super personal. I was just thinking “I have no reference point for this.” It’s formally a weird movie, I thought.

Then a week ago or so, it just suddenly hit me. One of my all-time favourite movies is The Gleaners and I (Agnès Varda, 2000), and I thought, “Wait a minute, that’s a movie about an idea! That has portraits of people, and she goes back to the people sometimes. There’s some autobiographical, personal stuff in it, but it’s not a memoir.” I realised 32 Sounds is in some ways exactly like The Gleaners and I as a form. I actually laughed and was like, I wish I would have realised that like six months ago. It would be a lot easier to just say I’m going to make The Gleaners and I about sound.

7R: You’ve talked about not wanting to bore people. There are filmmakers who make experimental films, and they don’t care that half of the audience are going to walk out. But it sounds like you really care about people being engaged, and being able to reach lots of people. How do you think about your audience?

Sam Green: There’re filmmakers who are like, “I don’t care what the audience thinks, or if people walk out. I don’t care.” I admire that, but I’m not that. I’m somebody who cares deeply about what people think. In both an insecure way, I want you to like my film, but also, if somebody is gonna pay twenty or thirty bucks, and maybe even get a babysitter, and take the time to come, I want to give them an experience.

I generally make films that I would want to see, and I want to be engaged and see something that connects with me. I get frustrated if it’s as if you’re just making a film for yourself and you don’t care what I think! Fuck you, why would I go see that movie then? I saw Brian Eno talk once, and he said something like, “I make things that I hope people will love” — something about being unabashedly into making things that people like. And Brian Eno is cool; it’s not like he’s pandering. But he cares, and I appreciate that.

7R: What are the plans for 32 Sounds? How are people going to be able to see this live documentary?

Sam Green: We have a website; there’s info there. We have a lot of live shows booked already. I mentioned Stanford, Abu Dhabi, the Wexner Center in Ohio, and there’ll be many more. The thing with most films is you show it for a year, and then it’s done; there are new films. With live things, I love that you can keep going. I did a show last weekend with the Kronos thing (A Thousand Thoughts). And The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller, we’re going to do something in April. So we will do shows for years with this. And hopefully, people will be somewhere nearby.

But also, with this one, as I mentioned, it can exist as a film. Because I’ve gotten equity financing, we’re hoping to sell it as a regular film. Sometimes, people have been like, well, aren’t the two formats going to compete? Josh Penner is the producer and gave a good analogy of, if there’s a musical artist you like, you will buy the record. But then you’ll also go see a concert. They’re not mutually exclusive. I hope this can be the same thing, where it could be a film that you might see on TV or online, but then, if there were a live show of it, you would see that, too.

7R: So there might be more virtual screenings for 32 Sounds, like what you did at Sundance?

Sam Green: The virtual screenings are something in between that. I don’t actually want to do that. I did that for Sundance, because I love Sundance, but I do feel like virtual screenings are, in some ways, the worst of all worlds. Either you should be watching it on your own, at your own time, like a podcast, or coming to a theatre. But a virtual screening is neither of those in a way that I’m not crazy about.

7R: Was there anything else that I should have asked you or that you’d like to add?

Sam Green: I really appreciate that you’re interested in documentary form, because it’s such an interesting thing. It’s a moment of super possibility, I think, in documentary form. For seventy years or something, the form was really prescribed by technology. There was a certain length of documentary that would show on TV, or in a theatre, or on VHS, or DVD. And the distribution landscape and everything was geared around that. It’s like the way pop songs are three minutes long, because that’s how long the recording can take. It’s sort of like the form was determined by technology way back, and it’s never changed.

Documentary form, in some ways, it’s still like that, and it’s so weird that we’re using ninety-minute films with a beginning and an end, just this very conservative form, because it’s always been like that.

Documentary form can be so many different things

At this moment, I think documentary can be so many different things that it couldn’t be in the past. In the touring I do, I project HD images that are fantastic from a laptop in Keynote. Twenty years ago, you never could have done that. Projectors couldn’t do that. This form could not have existed, and now it can.

There’s all this possibility, but it’s very rare that people are thinking about form. I think even episodic things are a radical new form: a documentary can be eight hours long, or if you think of documentary in a very loose way, podcasts. There’s the avant-garde world that thinks about form, and I love the avant-garde world, but it’s its own little tiny, marginalised [world]. I think formal inquiry and formal experimentation should be much more mainstream.

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch great films like 32 Sounds at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.

Click here to subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter.

Learn more about live documentary with the ebook Subjective realities

We talk to Sam Green’s collaborator Joe Bini, as well as Zia Anger, about their work in live documentary.