Jason James’s feature Exile (starring Adam Beach) and Bruce Miller’s short Conviction both tell stories of a previously incarcerated Indigenous man struggling to set himself free.

Exile had its world premiere at the Whistler Film Festival. Conviction previously screened at the ImagineNative Film Festival.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

Don’t miss out on the best films on the fall film festival circuit

Join our FREE newsletter today to become a Seventh Row inside. You’ll get updates on how to see the best under-the-radar films, up-to-the-minute updates from our festival coverage, and tips on where to catch these near you.

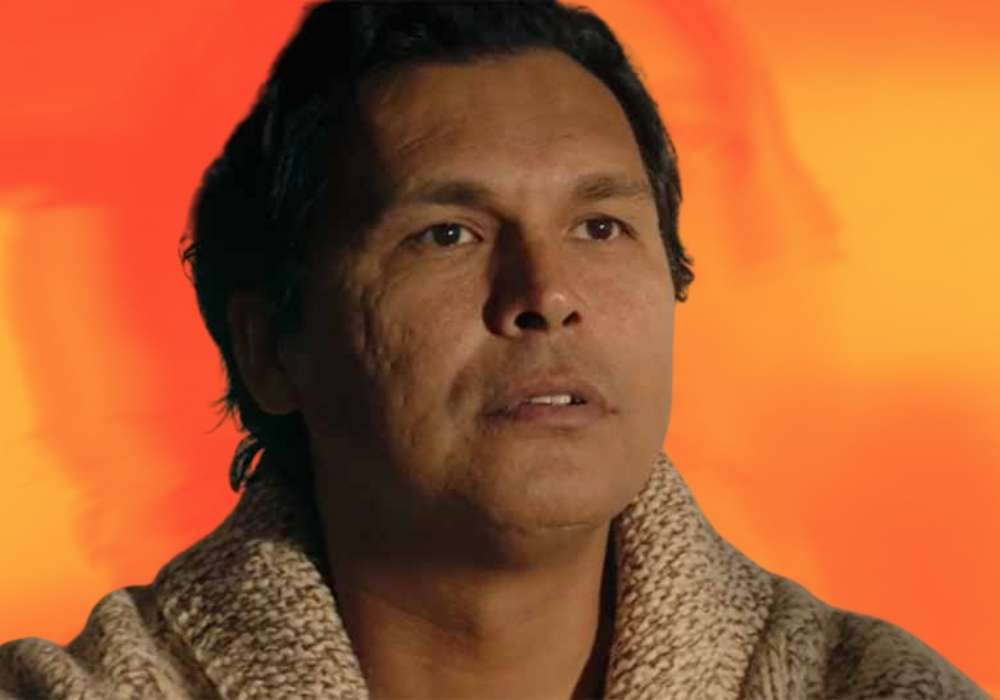

Any film that casts the great and still under-used Anishnaabe actor Adam Beach in a leading role is doing something right. Canadian filmmaker Jason James (Entanglement, 2017) had the good sense to do so for his latest feature, Exile, which premiered at the Whistler Film Festival. His recent supporting work in Monkey Beach (2020) was so charismatic and impactful that it felt like he had more screen time than he did; it was one of the best performances of 2020. Last year, he appeared for a disappointingly short bout of about two minutes in Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog.

So it’s a delight to get to see Beach in pretty much every scene of Exile, a thriller about Ted (Beach), an ex-con with PTSD who has isolated himself from his wife and family, out of what he thinks is a protective instinct. Beach is a compelling screen presence, and here, he goes through the emotional ringer — part action hero (or villain?), family man, and broken human. He’s never sure who he can trust or if anyone will ever believe him, and nobody is sure whether he is a reliable narrator of his own experience.

Set in the gorgeous BC countryside, director Jason James makes a film that is basically about two people in a room — Ted and his wife Sara (Camille Sullivan) — feel like it has a larger scale. After a few wide shots of the beautiful land, the film already feels more epic than its minimal locations and cast would suggest. Like so many Canadian films this year, from Viking to Coyote to The Swearing Jar, it feels designed for small Canadian budgets, which is also ideal for the required COVID safety protocols for film productions.

Though Exile is mostly an effective nail-biting thriller, that’s pretty much entirely because of Beach’s and Sullivan’s performances and screen chemistry. The script is weak, the characters aren’t particularly fleshed out on the page, and the plot is predictable. For better and worse, it feels like Beach was recruited to play a role written and designed for a settler. On the one hand, it’s so great to see Beach given so much to work with. As much as things are getting better in Canada, there still aren’t many Indigenous films getting made, and those that do get made are produced on a shoestring budget. There should be opportunities for Indigenous actors beyond that. On the other hand, it’s hard not to be disappointed that the screenplay didn’t adapt at all to the fact that Beach, and thus Ted, is Indigenous.

It’s almost unfortunate for Exile that Bruce Miller’s short Conviction, a much more thoughtful fiction film about the experience of an Indigenous man after incarceration, also screened at the Whistler Film Festival. Told often through voiceover and distorted images to get us inside the head of its protagonist, Conviction reminds the audience that it’s not uncommon for previously incarcerated people — especially Indigenous people — to continue to live in a prison of their own making after being released. Conviction also notes in its title card that Indigenous people are much, much more likely to be incarcerated in Canada than settlers.

By contrast, Exile feels lacking for failing to ignore the Indigenous context of Ted’s experiences. Here is a man who has literally made a physical prison for himself, and has barred his family from visiting him with restraining orders. And yet the film entirely attributes that to a possible external threat or Ted’s PTSD from the violent experience of prison itself. Exile never engages with the toll that colonialism would have had both on Ted’s prison experience, and how he has behaved since getting out. It would not be unreasonable for him to have a heightened fear of the police and the justice system — but everything gets attributed to just general PTSD as opposed to, say, intergenerational trauma. Ted’s self-isolation may also be a coping mechanism, rather than simply paranoia run mad.

It’s unfortunate that Exile never probes these potential psychological depths because Beach would be up to the challenge, and it would have made for a more thoughtful film. Instead, the characters in Exile feel constantly under-written, if elevated by great performers. Exile feels mostly like a good excuse to watch Beach give it his all, and that’s a worthy end, though the film never lives up to his work.

You may also like our reviews of other films like Exile starring Adam Beach and other Indigenous actors…

Become a Seventh Row insider

Be the first to know about the most exciting emerging actors and the best new films, well before other outlets dedicate space to them, if they even do.