Alex Heeney reviews the Soulpepper Theatre’s remount of their 2019 production of A Streetcar Named Desire, directed by Artistic Director Weyni Mengeshi. The production updates the performances to reflect modern mores to mixed results as the interpretation clashes with Tennessee Williams’ text in the second half.

CREDIT: DAHLIA KATZ

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

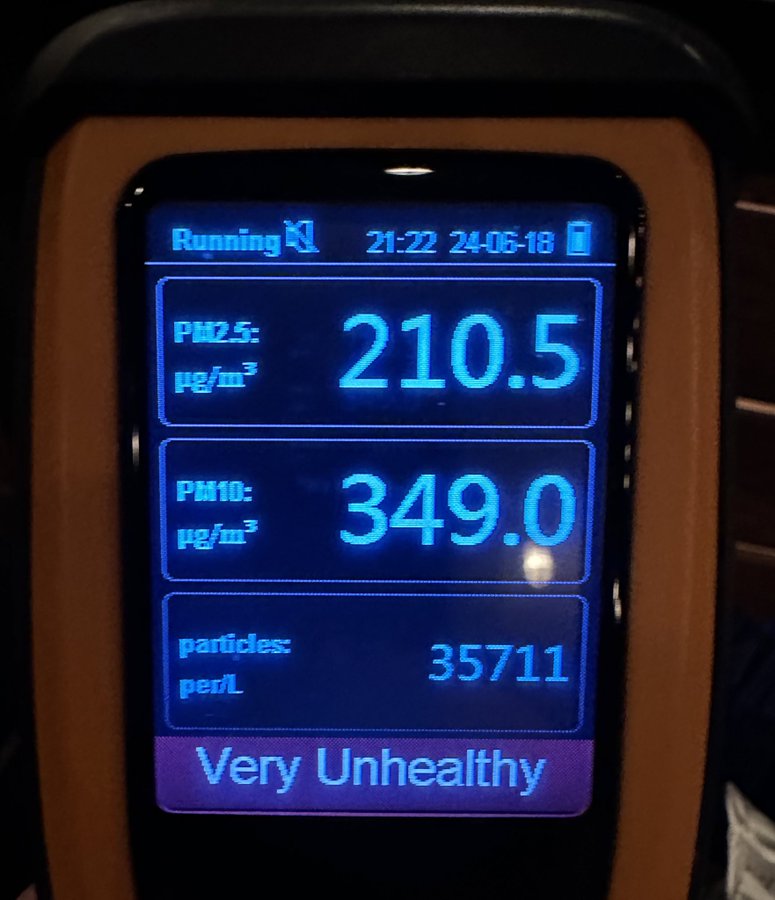

Health Warning: The indoor air quality at this production is extremely poor, with particulate matter (PM 2.5) levels exceeding the levels during last year’s dangerous wildfire smoke in Toronto. Please use caution. More details at the end of the article. These PM levels were 13x the WHO recommended 24-hour exposure levels, which should not be exceeded more than 3-4 days per year.

In the remount of her 2019 production of A Streetcar Named Desire, Weyni Mengeshi updates the supporting performances to reflect modern mores to mixed results as the interpretation clashes with Tennessee Williams’ text in the second half. In the production’s opening, fallen Southern Belle Blanche Dubois (Amy Rutherford) wheels on her hardshell suitcase. We’re not in the 1950s, although Blanche’s wardrobe wouldn’t exactly be out of place there either.

When Blanche arrives at the doorstep of her sister Stella (Shakura Dickson) and her husband Stanley (Mac Fyfe), we soon realize that Blanche behaves not just melodramatically, but as if she’s in another world and, perhaps, another play. That’s by design, for better and worse. Blanche is all smoke and mirrors. Is she a widow or a maid? She keeps changing her story. How did she ‘lose’ the plantation that she and Stella grew up in and end up so destitute as to constantly be relying on the kindness of strangers? What does Blanche even want to achieve by showing up here?

Shakura Dickson’s no-nonsense Stella

Shakura Dickson’s scene-and-show-stealing no-nonsense Stella, by contrast, lives in the real world. She’s preoccupied with the practicalities of an expectant mother, ready to relax when she can, party when she can, and do what she can for her helpless dear sister. She doesn’t treat Blanche’s arrival as an imposition so much as a bonding opportunity and a chance to lend support. If she’s been marked by a childhood with Blanche, it’s only intensified her compassion rather than traumatized her into choosing controlling relationships. In other words, Mengeshi is reluctant to make the connections in the text between Blanche’s and Stanley’s overbearing behaviour toward Stella.

Realist performances from everyone but Blanche in Soulpepper’s A Streetcar Named Desire

Indeed for one of Tennessee Williams’s most intense melodramas, Mengeshi leans away from the melodramatic as often as possible. While Rutherford gives a fairly standard interpretation of Blanche, the woman who can’t or won’t look at reality, the rest of the performers act in a more realist register. Stanley and Stella are a passionate if not troublesome, initially, duo, who offset Blanche’s overly dressy costumes and airs of gentlewomanly behaviour with down-to-earth working-class respectability. Stanley’s temper may be volatile, but he doesn’t read as wholly dangerous except perhaps to Blanche. Even Blanche’s gentleman caller reads less as a pathetic mark or an overbearing brute so much as a sensitive man who’s taken with Blanche and wants to get to know her, warts and all.

BAND ENSEMBLE: OLIVER DENNIS, DIVINE BROWN, SEBASTIAN MARZIALI AND KALEB HORN in Soulpepper Theatre’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire.

The production’s most frustrating choices are also among its most intriguing. Whether to accommodate a live band or because she had one, Mengeshi chooses to extend the sequences between scenes with long moments of dialogue-free performance. Since the band is good and, along with the women’s drawls, the sole indication we’re in New Orleans, it’s a useful stage setter. (Characters in this production rarely look like they’re enduring sweltering heat, especially noteworthy for a show premiering in the middle of Toronto’s first major summer heat wave.) Sometimes, the transitional business can be revelatory, like watching Stella drunk dance as she waits for her sister to give birth. It means she’s out of it when Stanley comes home and, as she tells it, attacks her. More often than not though, it makes the production feel shaggy, like the transitions are under-rehearsed and slow.

Mengeshi makes key onstage moments of the play deliberately ambiguous

When a drunk Stanley takes a swing at Stella, it happens far upstage, and so messily that we’re not sure whether he ever actually connected with her. There is no thwack of connection between his arm and her body and she wears no bruised makeup in the following scenes. It’s unclear if this is meant to make us believe Stella’s side of the story, that he just gets bad when he’s drunk but is no real danger. The characters all treat Blanche’s horrified reaction as an overreaction, but even attempting to hit your wife with a miss still seems pretty bad to me – bad enough to that it’s hard to believe the self-possessed Stella would come back to him so quickly.

The sequence, though, is not entirely convincing, with Stanley crying, almost out of nowhere, after the five-minute loss of his wife to the upstairs neighbour. We watch them make up and get it on, as if nothing bad happened. If you’ve seen any other production of Streetcar or read the text, it’s a bit hard to believe. Stanley’s volatility and abuse is all over it. In Mengeshi’s production, it’s as if that volatility and abuse are only visible to Blanche, and we don’t get enough information either way to quite know who to believe, despite seeing everything play out. The refusal to pick an interpretation while making each of these moments explosive yet vague hinders rather than helps the production.

Is Stanley’s abuse all in Blanche’s head?

More frustrating is how the production treats Stanley’s attempted rape of Blanche. He rolls her on the bed upstage – the first time the bed has been wheeled about in the production, so it’s meant to get our attention – and while standing over her as if to thrust, red lights and loud music play overhead. It’s a far cry from Julie Taymor’s sleeves of ribbon as an obvious if artistic stand-in for blood. We don’t know if this is a stand-in for rape or for Blanche’s imagination of rape or the threat of it. Putting us into Blanche’s perspectives for these moments might work if the entire play stayed in her subjectivity. But Mengeshi has deliberately separated us from Blanche’s subjective reality throughout the rest of the production: she’s the only one not acting like it’s 2024.

Mengeshi’s thoroughly modern production clashes with the ending of Tennessee Williams’s text

Aye, there’s the rub. Although there are no cell phones or other indications of modern times, the costumes are just modern enough to read as 2024 and timeless enough to almost be as convincing as from another era. Everyone but Blanche is so busy acting thoroughly modern that it comes as a jarring surprise when Stella suddenly cedes all decisions about Blanche to Stanley, even though she’s not sure he’s right. Wouldn’t this lively, empathetic Stella opt to talk to her sister, to get her modern mental health care rather than have her committed like it’s the dark ages? Unfortunately, that’s not how Williams’ text of repressed emotions ends. And Mengeshi never convincingly shows how the characters could make the transition from such understanding people to such cold ones.

The production’s many pleasures

Still, the show offers many pleasures. The set design by Lorenzo Savoini offers multiple spaces outside of Stella and Stanley’s apartment on multiples levels, which Mengeshi makes use of throughout the play as a release valve from the central tension. The music from the live band and transitions also offer an opportunity for a breather from one intense scene to the next. In a play over three hours, it can be easy to get sleepy or zone out, but Mengeshi has paced this production to keep you engaged and alert.

Finally, even if the show didn’t have so much food for thought, albeit to mixed results, it would be worth seeing for Shakura Dickson’s performance as Stella. While most of the core cast has returned from the 2019 production, Dickson is a new addition, and a fantastic one. She’s so good that the Streetcar neophyte friend I took with me to see the production was convinced, by intermission, that Stella was the star of the play. Such is the power of star quality.

Health Warning (continued) for Soulpepper Theatre’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire

Particulate matter readings inside the Baillie Theatre at intermission of Soulpepper Theatre’s A Streetcar Named Desire

Particulate matter readings inside the Baillie Theatre at intermission of Soulpepper Theatre’s A Streetcar Named Desire CO2 levels inside the Baillie Theatre remained below 1200ppm throughout the production.

CO2 levels inside the Baillie Theatre remained below 1200ppm throughout the production.

The theatre was smoky before the play began. The particulate matter levels were as dangerously high as outdoor levels during last year’s wildfires (PM 2.5 was around 200μ/㎥). WHO recommends that PM2.5 levels should not exceed 15 μ/㎥ in a 24-hour period, and this should not be exceeded more than 3-4 days per year.

This makes the Baillie Theatre a dangerous space to enter without an N95 respirator, and especially for pregnant people, people with breathing issues, asthma, allergies, or other sensitivities to poor air quality. California Air Resources Board details some of the health effects of PM 2.5 here.

I saw the show on opening night, when Environment Canada was warning that outdoor air quality was very poor. The PM 2.5 levels I measured outside the Soulpepper Building were ~20μ/㎥, meaning the theatre was 100x more hazardous.

That said, the COVID hazards are lower than other Toronto venues, with CO2 levels staying below 1200ppm throughout (for comparison: a full TIFF Cinema 2 would be 2500+ ppm, the Bluma Appel Theatre reached 1600 ppm after a 90-minute show in the winter).

Editor’s note (updated June 29): The poor AQ inside Soulpepper seems to be coming from the Michael Young Theatre next door. I went to see Age is a Feeling there on Saturday, the 29th, and had to leave because the PM levels were so high, they were off the charts for my meter (999+ μ/㎥), which is entirely hazardous. This suggests that the poor AQ at Streetcar (Baillie Theatre) was a diluted version of the poor AQ in the theatre next door. AQ this bad is extremely rare and speaks to a problem with the building, making Soulpepper a hazardous environment until they address this issue.

Related reading/listening to our review of A Streetcar Named Desire at Soulpepper Theatre

Streaming Theatre: Listen to our podcast on the NTLive production of The Deep Blue Sea, also about a complex woman in a domestic environment. Read our essay on Terence Davies’ The Deep Blue Sea, which adapts the play for the screen and puts us inside the protagonist’s unreliable headspace. Mengeshi’s production attempts to do this on stage, but it’s inconsistent so works less effectively.