Alex Heeney reviews Lester Trips’ inventive and invigorating production of HONEY I’M HOME, part of the Factory Theatre’s season of shows about AI and technology..

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

It feels entirely à propos that I saw HONEY I’M HOME, the latest play from the incredible Lester Trips team at Toronto’s Factory Theatre, after a two-day screen detox because I’d been getting uncontrollable dizziness and migraines from computer use. Early on, the play’s protagonist, Janine (whose digital and physical selves are played by both Lauren Gillis and Alaine Hutton), finds herself in her own digital hellscape, where she, too, is dizzy and nauseous.

Programmed as part of the Factory Theatre’s series of plays about and inspired by technology and AI, which included I Don’t Even Miss You (Oct 31-Nov 10), HONEY I’M HOME is one of the best, funniest, and most inventive plays I’ve seen this year, and indeed, in a long time. Co-artistic directors, writers, and performers Gillis and Hutton mix Butoh-based Embodiment (which they trained in with Denise Fujiwara) with Fides Krucker’s Emotionally Integrated Voice approach to extended range vocals. Essentially, it’s physical theatre that’s just as interested in voice and text work.

The play opens with a prologue: a woman (Alaine Hutton) who barely moves and never speaks is tended to by a nurse (Lauren Gillis) in an elaborate headdress recalling 19th-century European nurse costumes. The nurse breaks the fourth wall to explain that the woman she is caring for has “idiopathic catatonia” and was rescued from a storage unit by her organization. The nurse sings to the woman, hoping to evoke a response, asking the audience to join in. Hutton’s hand and body make some sudden jolts, but we’re not as convinced that it’s a sign of thought as the nurse its. The setup, though, is a good encapsulation of the duo’s working dynamic: Gillis provides the voice work and Hutton, who is never heard in the play, most of the embodiment.

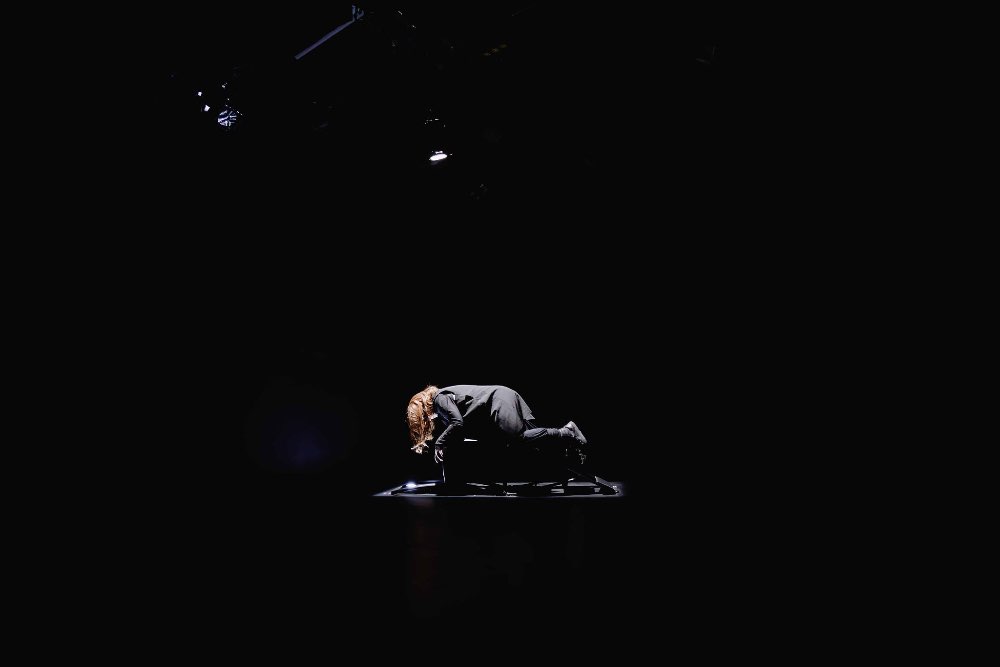

The real action begins with Janine, who we meet bent over a computer station at work, making the same jolted movements as the woman with idiopathic catatonia, asking us how much digital spaces have forced us to become disembodied workers. Janine isn’t seated, though; she’s horizontal as if prostrated over her digital workspace, which looks up at her from below. She communicates with her boss and digital workspace through exaggerated nods of the head.

We learned that her request to work from home has been denied. Even though all of her work involves interfacing with a computer, safety issues require someone to be on the premises. Instead, she is offered access to a virtual home: essentially, a virtual reality she can visit while at work, which transports her into her actual home without being able to touch anything physically in her home.

Her first trip into it offers a compelling possibility: the ability to scream while at work. But she has to train herself to scream in the virtual reality without moving her body at work. We watch as Gillis, seen behind a cutout frame, screams in the virtual reality while her body, elsewhere on the stage, jolts and jolts before learning not to move at all. It’s a canny metaphor for how work is increasingly a space of trying not to show on the outside that you’re screaming on the inside. But it’s physically overwhelming for Janine who soon has to leave her virtual home because it’s making her dizzy and nauseous, a common symptom if you’ve not yet invoked a digital avatar, who Hutton will soon play.

Throughout the play, Gillis is trapped behind a panel with a rectangular cutout, narrating the action as the woman experiencing the digital space. Hutton, then, plays Janine’s digital avatar and real self inside her apartment, the real and digital space increasingly indistinguishable from one another. Very quickly, we willingly suspend our disbelief that Janine has two sets of divided selves: virtual and real, physical and intellectual. Gillis is the brain and voice; Hutton is the body, both digital and real, and it’s never quite in sync with its engine. Both are incredibly expressive, but the disconnect between the cogent thinking of the voice and the jerky, confused movements of the body are where the production draws so much of its power.

On the first evening, when Janine returns home, Hutton arrives in the apartment to a paralyzing to-do list. Her movements are jagged. Gillis serves as her inner monologue, reminding her to put her coat on the rack, unload the dishwasher, log into the digital debt management portal, and so on. Every move Janine makes to complete one of these tasks is interrupted by the reminder of yet another task she has to do. Away from her workstation, where she’s forced to stay stationary, Janine jerks around in her home, trying to accomplish tasks without getting to any of them. By the end of the production, after multiple trips home, she still hasn’t managed to put her coat on the rack.

Inside her virtual home, Janine can’t accomplish anything for another reason: seemingly simple actions require multiple excruciating steps. She can interface with her digital appliances but not with any real things in her apartment. An attempt to do the dishes fails when she realizes she’s turned on an empty dishwasher and cannot load it up first while still at work. When the virtual space makes her so sick that she needs a sick day, she struggles to interface with her virtual assistant and leave a voice note for her boss. There are miscommunications over when the recording will begin, whether the note is actually being saved, and if the recording will be sent.

Although we never see a computer screen on stage, aside from the bright light that shines in Janine’s face at her workstation, HONEY I’M HOME is the best encapsulation I’ve seen of what it’s like to deal with a computer and interact with virtual spaces. Much of the production dramatizes how simple communication involves endless steps because Janine has to explain to the computer what you need it to do – click this, then that, do this, then that, all to do something that would have once been done by picking up the phone (or by talking to the person next to you!).

The more involved we get with our virtual lives, the more we can feel like brains with infuriating bodies attached to them, bodies we don’t care for or can’t control. At one point, Janine chastises herself for not being able to sit completely still for ten hours straight, a moment that got huge laughs because, of course, it’s a preposterous request that is part of so many of our working lives.

With just a one-week sold-out run, HONEY I’M HOME is a polished, hilarious, and thought-provoking production. And that is in such short supply when even large, well-funded production companies are turning to one-man shows with famous actors to cut costs. HONEY I’M HOME is small in scale but huge in scope and ambition. It’s the kind of show that excites you about the possibilities of theatre.

Related reading/listening to our review of Lester Trips’ Honey I’m Home

Personal Shopper is one of the best films about the hellscape of living in our technology. Read our Special Issue on the film, which includes an essay about the challenges we (and the protagonist) have distinguishing between technological obsession and depression in the film.