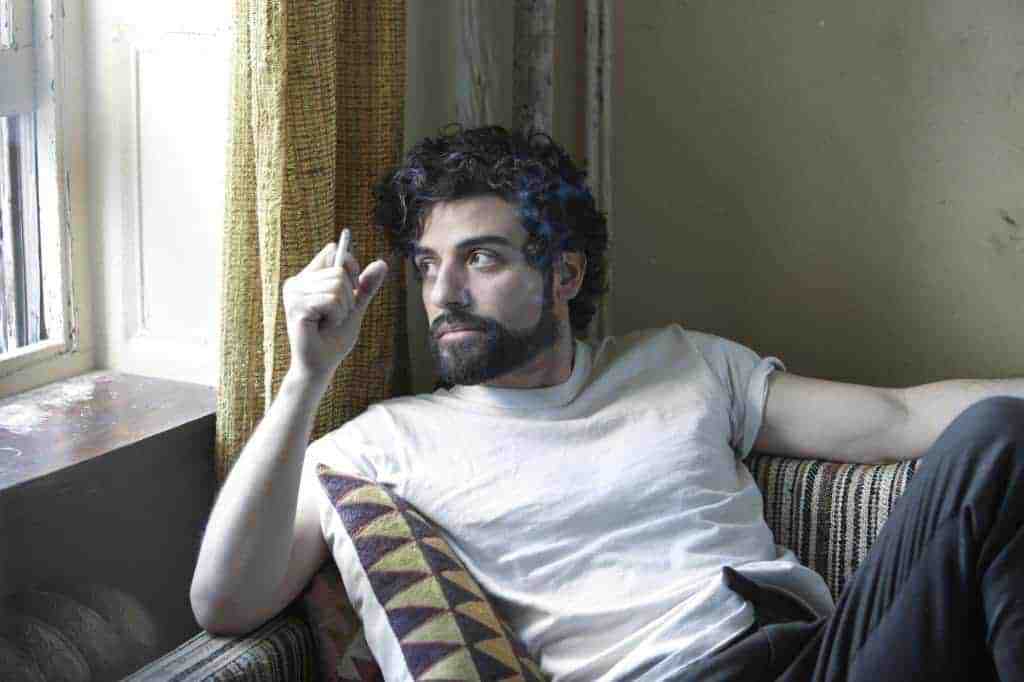

Inside Llewyn Davis opens on a closeup of Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac) singing and strumming “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me”, surrounded by darkness. It’s a mesmerizing and evocative shot, which immediately renders Llewyn iconic, performing this haunting, bare bones ballad. Slowly, the camera pulls back to reveal Llewyn on stage, and then the stage in the Gaslight, the famous folk music venue in Greenwich Village, and its eclectic patrons. Once the stage is set, we find ourselves focussing intently on Davis again.

It’s a microcosm of the film as a whole, which presents the abrasive Llewyn as an impressive but underappreciated talent, whom we look at both in wonder at his stage presence and in condescension towards his foibles and hopelessness. And while we may feel moved by the music, there’s a dark undercurrent in it, too.

The film impressively paints the backdrop of the 1960s folks scene that Llewyn is a part of, but always through his eyes, and through his story. Working with a new cinematographer, Bruce Delbonnel (Amelie, Across the Universe), the Coen brothers bring a real sense of atmosphere in the film, whether of the dimly lit club full of cigarettes or the snowy, New York City of the past, like an old record cover come to life.

We traverse New York City with Llewyn, our itinerant guide, who spends his nights trespassing on the hospitality of his Greenwich Village friends, until they tire of him. Then he’s forced to camp in the Upper West Side, where his former singing partner’s parents reside and gladly take him in. His career isn’t going well, but he refuses to call it in, even though he can’t even afford a winter coat, let alone rent.

There’s a beautiful sequence of Llewyn making his way downtown from Morningside Heights through the subway, watching the stations pass by: he’s always on the move, but as it becomes increasingly evident, going nowhere in his career or in his development as a person. We follow Llewyn for about a week, as he moves from address to address around New York, drives out to Chicago, and back again. This is very much a Ulysses-esque journey like Joel and Ethan Coen’s previous, also musically-inclined film, O Brother Where Art Thou, but the characters and the landscape here are even richer and more complex.

Llewyn is barely tolerated by his friends since he’s utterly tactless and generally self-absorbed. His former lover, Jean (Carey Mulligan), refers to him as King Midas’s idiot brother who turns everything he looks at to shit. When she first declares it in anger – she’s pregnant, possibly with his child although she’s in a relationship with Jim (Justin Timberlake) – it seems like funny hyperbole, but it proves surprisingly true. You want to like Llewyn because it’s impossible not to like his impassioned music, but he’s very difficult to like or sympathize with: he gets himself into deeper and deeper trouble and repeatedly hurts the people around him.

It’s not that he’s deliberately cruel. He’s just too caught up in his own pain and loneliness to have any room for compassion. He’s frustrated that he’s not any closer to making it big, while showier but less gifted acts, like his friends Jim and Jean, always find gigs, work, and money. He copes with the disappointment by taking on an air of snobbishness. He refuses to sing and play for his friends, who kindly ask him to, by insisting it’s his job and his oeuvre is not for show, which certainly doesn’t help to endear him to them. He also won’t take long-term musical work that he considers beneath him, like working as a sideman rather than having full creative control.

There’s a foreboding feeling hanging over the film, like we’re waiting for Llewyn to come to terms with his own failure and unimportance. Although there are some very, very funny parts, most notably the recording session for Jim’s vapid song “Please Mr Kennedy”, the film is not a black comedy, but rather a sad drama with occasional comic relief.

Oscar Isaac is a musician, and he sings and plays his own parts in the film with a wealth of emotion subtly communicated. As the film progresses, and the disappointments accumulate, we see the fatigue, the desperation, the loneliness, and the sadness mount, especially in his musical performances. And it’s when he’s performing that Llewyn seems the most human, singing someone else’s old words that seem surprisingly fitting for him; this at least prevents him from tripping over his own unkind words. In his daily life, he’s full of anger and indignation at his situation and the cruelty of a world that won’t recognize his talent. He’s unable to form meaningful relationships with others. He unapologetically often fails to even connect with his audience, although the tight closeups on him create a deep connection with the film’s audience,

The Coens put many sign posts of meaning along the way, including a friend’s cat that Llewyn finds himself taking responsibility for although he’s incapable of being responsible for anything else. In a lesser film, these could easily be cliches, but as a film about a man who can’t accept his limitations and fate, which may not be fair anyway, it’s fitting that these aren’t signs that Llewyn or we can read clearly.