Photo by Natalie Jenison, © Tim Jenison, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

In a time when painters were rigourously trained, how did the untrained Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) create such luminous, lasting masterpieces? According to inventor-techie Tim Jenison, he may have been equally adept at tinkering and made use of optical devices to help create a realistic look. Jenison sets out to prove this theory in Teller’s new documentary “Tim’s Vermeer” by very accurately re-creating Vermeer’s seventeenth century studio conditions, and attempting, without ever having picked up a paintbrush before, to reproduce Vermeer’s “The Music Lesson” with the help of a lens and a couple of mirror.

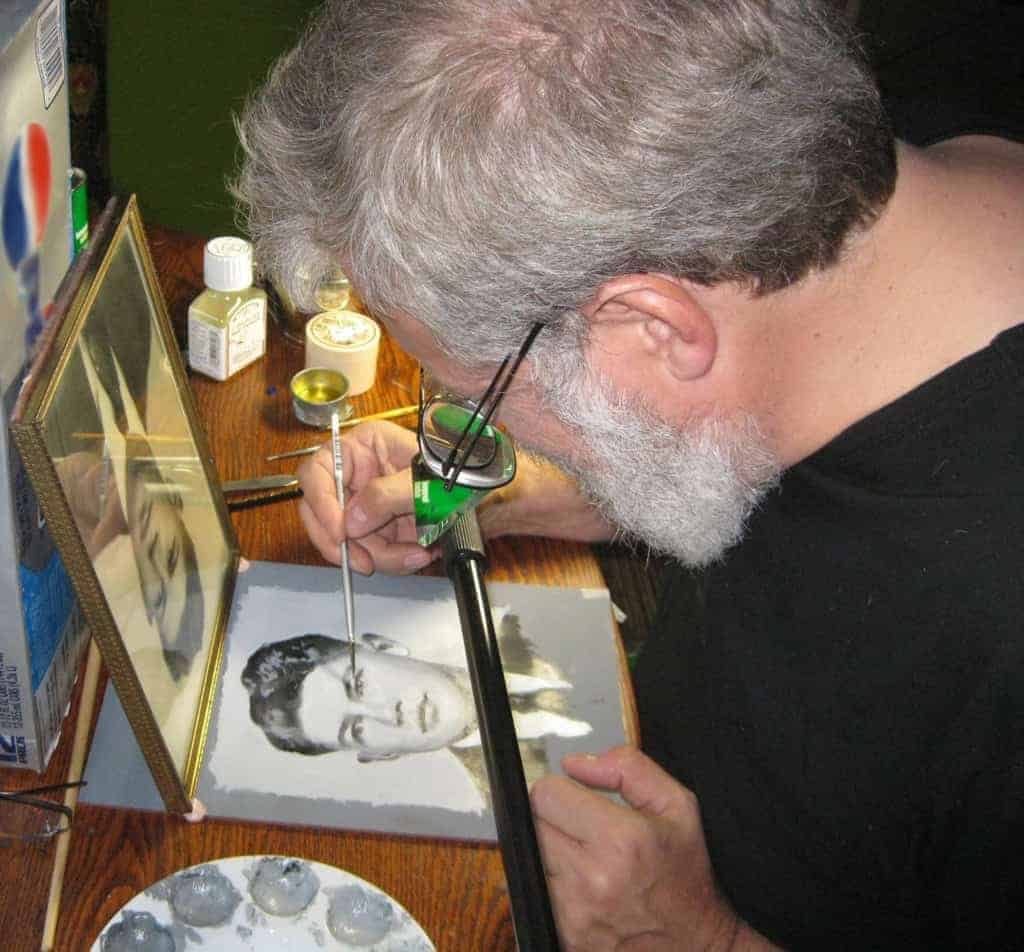

Photo by Farley Ziegler, © 2013 High Delft Pictures LLC, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved.

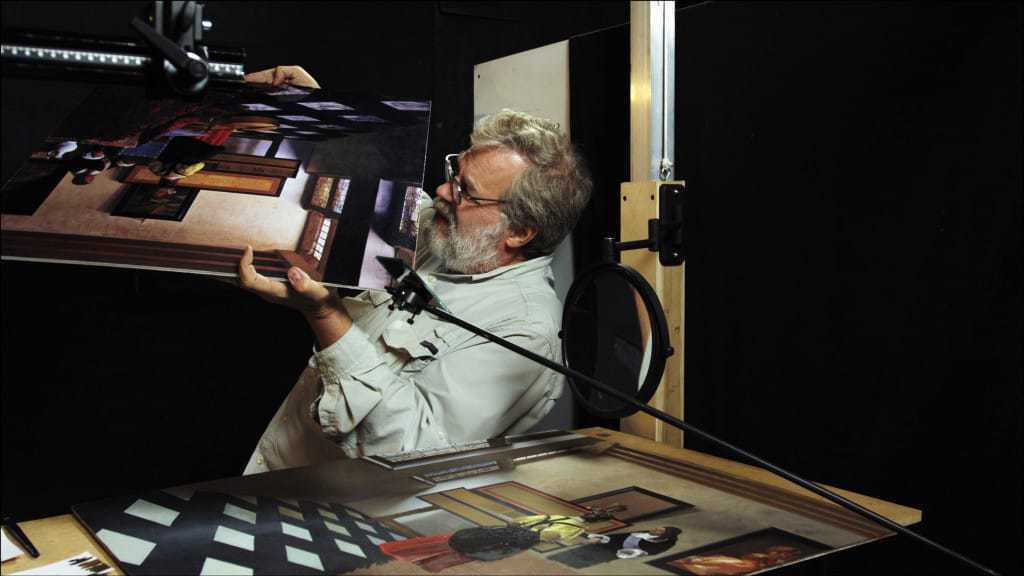

That Vermeer and other painters may have had help from optical devices, such as the camera obscura, is not a new idea. In his 2001 book, “Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters”, British painter David Hockney argued that the revolution that painting underwent in the Renaissance, to resemble more photographic and realistic images, was because artists began to use optical aids rather than merely the evolution of technique and skill. Architecture Professor Philip Steadman wrote the book “Vermeer’s Camera”, which took an in-depth look at seventeenth century optical technology and explained the science behind how Vermeer could have used a camera obscura to make his paintings and how this would have resulted in the geometry depicted. But Jenison’s experiment is the most high fidelity attempt at unequivocally proving that optical devices could have been what allowed Vermeer to paint like Vermeer.

Jenison’s multi-year journey begins with collecting all the data about the objects that appeared in Vermeer’s “The Music Lesson” and build reproductions of these. He builds a 3D computer model of the entire space, and then constructs all of the pieces himself: he’s an amateur carpenter unafraid of cutting his lathe in half when it turns out to not be quite big enough for one of the pieces he needs to make. He rents out a warehouse in San Antonio, Texas, which he renovates to look just like Vermeer’s studio, and even makes sure that the same shadows would be cast through the windows, by projecting the image of the old church in the Delft town square, which his studio overlooked, onto a screen outside.

Jenison also experiments with optical technology that would have been available to Vermeer to figure out what he would have needed. He starts by building a gigantic dark room – a camera obscura – in the studio, but is disappointed to discover that seventeenth century lenses would not have produced a clear enough image to work from. But if coupled with a mirror, the image would be sharp enough, and the dark room would no longer be necessary. Since copying from the camera obscura image directly is too problematic, he discovered that using a second, smaller mirror, onto which he could project it would allow him to copy the image onto the page. It’s a slow and tedious process, which makes the film feel the same towards the end, but Jenison’s perseverance and singular vision keep the film engaging.

Once the painting begins, he makes some discoveries, which provide particularly good evidence that Vermeer likely used the same methods. When copying the seahorse pattern from the harpsichord, Jenison noticed that his copy produced a curved harpsichord and a distorted and curved seahorse pattern. Comparing this to a print of Vermeer’s painting, he found that although Vermeer corrected the shape of the harpsichord, the seahorse pattern was distorted in exactly the same way as Jenison’s was because of how the lens refracted the light. If Vermeer didn’t use optical devices to paint the picture, how did he end up with the exact same ‘mistake’ as Jenison did when using these methods?

Although the film makes a convincing and fascinating argument for how Vermeer could have seen and painted like a photographer before the invention of photography, it doesn’t take the argument quite far enough. Given that it took Jenison 130 painstaking days to produce “The Music Room”, would Vermeer have been able to produce his 35 known paintings in the 43 short years of his life, had he been working at a similar pace? By focussing on whether ingeniously using technology is “cheating”, Jenison misses the opportunity to explore why Vermeer’s work is so remarkable. It’s not just the light effects in “The Girl with the Pearl Earring”, which showed at the de Young Museum early last year, that has made it the ‘Dutch Mona Lisa’: it’s her inviting and enigmatic expression, the exoticness of her dress, and the composition. The technology needed to create these effects is important, but it’s hardly the whole story.