Orla Smith and Ben Flanagan pick their four favourite competition short films at the 2019 London Film Festival. Read more LFF coverage here.

Short films, so often overlooked, are always one of the most interesting elements of an film festival. Within short film strands you discover the great filmmakers of the future. At the 2019 London Film Festival, correspondents Orla Smith and Ben Flanagan picked out four standouts in the short film competition. These are both promises of great work to be done in the future, and brilliant pieces in and of themselves.

Fault Line (Gosal, dir. Soheil Amirsharifi)

This 15-minute drama from Soheil Amirsharifi is a perfect distillation of Iranian cinema’s famous use of realism and metafiction to avoid censorship. Beginning in a classroom at a girl’s school during an earthquake drill, Fault Line uses ecological uncertainty to tell a story about justice and instability within a peaceful neighbourhood.

Amirsharifi shows an injured girl in trouble and her friends plotting to help her by using a performance for CCTV to create a new reality. The viewer’s lack of knowledge about the girls’ culpability opens up across a few short scenes as we learn more about the circumstances behind the injury. Schoolyard problems are used as a microcosm of Iranian approaches to justice and retribution, where the law is definitive and your honour is at stake. The cast play it so straight that the obvious ways the characters fit into types (the rat, the good girl, the lawmaker) are hidden by the superficial naturalism.

Amirsharifi has crafted an ingenious and plausible scenario that reflects how reality can be moulded by whatever we agree to be true, like how we assume the CCTV camera captures truth. Bazin’s mummified image strikes again. All this is presented through plain, patient camerawork that puts across the drama without adornment. As Amirsharifi switches between the subjective camera and the CCTV, questions of the viewer’s role as spectator become pertinent. If we are asked to question the CCTV, then why not the handheld camera? – BP

Fault Line won the competition award for Best Short Film at LFF.

In Vitro (dir. Larissa Sansour, Søren Lind)

Twice as long, and probably twice as epic as anything else in this programme, this glacial, future-set Palestinian sci-fi pushes the short film form to its limit, in that it questions how slow cinema can be applied to a film with a limited run-time. For a short film, 30 minutes might as well be the equivalent of a Satantango-length movie. And In Vitro is, quite purposefully, obtuse in warning the audience about the effect of an eco-disaster on place and community.

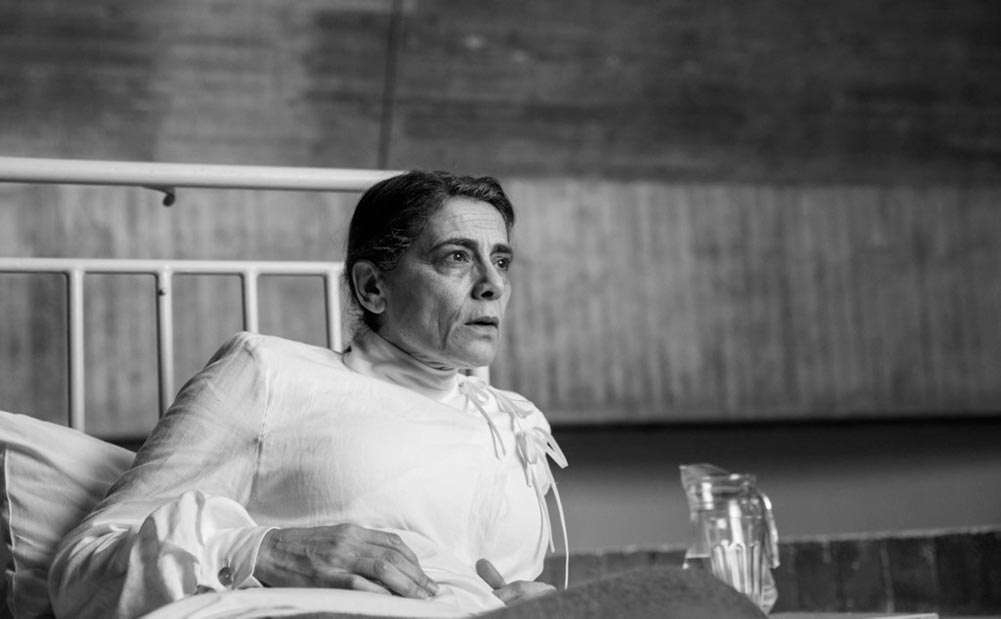

Set in an underground bunker where an orchard slowly grows, the last woman to remember life before the disaster recalls how this new world came to be, as she lays dying. Lind and Sansour use intense on-screen darkness to highlight contrasts in the dramatically-staged tableaux, with bold use of split-screen showing shot and reverse-shot at once. Harrowing archival footage of Palestine shows a dystopia already inhabited by millions, with genocide effectively completed by environmental collapse.

Does its oblique way of storytelling through symbolic visuals and poetic dialogue speak to an audience outside of the art-gallery set? The film is not so didactic as to give us straight facts, nor does its storytelling present a metaphor strong enough to inspire a viewer to action. However aesthetically striking, In Vitro makes one question the function of a short film about the environment, other than as a wheel-spinning gesture on the part of galleries and commissioning bodies. What should environmental cinema look like? – BP

Watermelon Juice (dir. Irene Moray)

Pol (Max Grosse Majench) and Bàrbara (Elena Martín) are, by all intents and purposes, happy. While holidaying with friends in Catalonia, everything is drenched in beautiful, bright sunlight. They gaze at each other adoringly, joke with and jostle each other with casual affection, and their disagreements are easily diffused with open communication.

Director Irene Moray’s touching Watermelon Juice follows the couple’s little excursions away from their group of friends, whether that’s having sex in the morning or lazing by the river in the afternoon. The couple’s conflict is something so rarely acknowledged in cinema: throughout their relationship, Bàrbara has been unable to orgasm due to previous sexual trauma. Despite the pair’s healthy, loving, supportive relationship, it’s a weight that pushes on them both. Pol is desperate to make his girlfriend happy and Bàrbara’s issue is compounded by the pressure she puts on herself to perform, especially when she knows how happy it would make Pol if his efforts succeeded.

Moray’s greatest achievement is making something constructive and even sweet out of stigmatised subject matter. Watermelon Juice is a wistful, beautiful film about a strong and stable relationship, observing the central couple with lightness, humour, and gentleness. In one scene, Pol brings Bàrbara slices of watermelon to eat, having heard that watermelon has sexually-stimulating properties. The two laugh over Pol’s sweet, silly gesture. Ultimately, it’s not the watermelon that helps Bàrbara to come, but the comfort she feels with Pol, knowing that whatever happens, he’ll support her, and that they can laugh about anything together. – Orla Smith

What Do You Know About the Water and the Moon (dir. Jian Luo)

This story of a woman who is surprised to find that her aborted foetus is actually a jellyfish, has the makings of a political parable but is, surprisingly, more of a psychological journey through modern China. Beginning in a fake looking studio apartment that’s artificially dank and gross, as though made on a green screen, Luo situates us in a bleak world that looks part Cronenberg, part-2046, where a woman is trying to conduct a home abortion, which fails, forcing her to go to hospital. Leaving her house, the film suddenly opens up to a city of vast filmic possibility, from the sheer scale of the buildings en route, to the clinical horror of the hospital where staff dismiss her concerns and withhold information.

Luo shoots this journey, not as a dream, not as a nightmare, but as something else: a cartoon reality. This woman’s journey is a tour of a city which grows wider until we reach a final shot of vast scale. She releases the jellyfish into the city’s river, completing some kind of reproductive cycle, and accepting that nature’s relationship with industrial China isn’t a battle but an ongoing negotiation, when the jellyfish appears to light up the city itself. A lot for 17 minutes, but Luo’s film gestures to a vision beyond the bounds of length. – BF