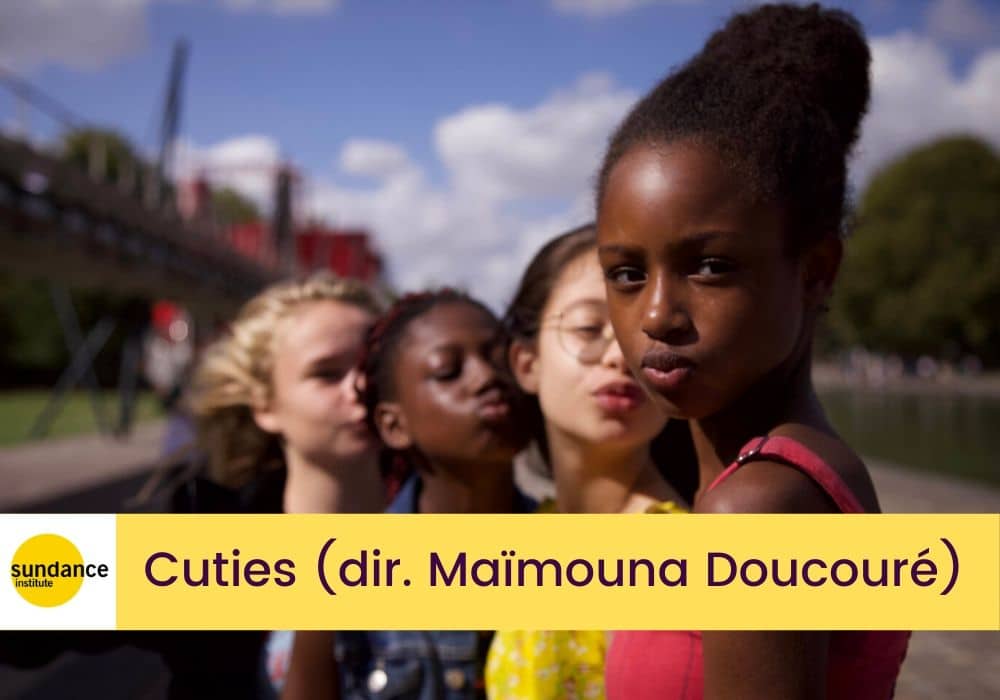

Maïmouna Doucouré’s Cuties is an often compelling crowd-pleaser, if somewhat under-baked, which looks at how girls end up becoming over-sexualized at a young age.

*Screening in the World Dramatic Competition, Mignonnes (Cuties) has already been scooped up by Netflix.

Sure to be a crowd-pleaser for its joyous scenes of a group of eleven-year-old girls dancing, Cuties is an often compelling if somewhat under-baked look at how girls end up becoming over-sexualized at a young age. Cuties follows Amy, a Senegalese immigrant new to Paris, who is caught between her devoutly religious family in upheaval — her father has just taken a second wife and has yet to join them in France — and her desire to be part of a group of French girls at school who love to dance.

Maïmouna Doucouré’s feature debut often feels inspired by Céline Sciamma’s Girlhood, which follows a teenage girl, Marieme, seeking community. Both use shot-reverse-shot techniques to show us the desirable group that the protagonist wants to belong to — often glimpsed dancing — and the lonely protagonist staring at them in awe. While Sciamma explored Marieme’s struggle with performing femininity and masculinity while seeking freedom from oppression, Doucouré’s Cuties explores how young girls are sexualized, often by choice but without understanding the consequences of this sexualization.

In Cuties, Doucouré constantly highlights the disconnect between the girls’ awareness of their own sexuality and how they’re perceived. When we meet Amy’s first friend, she’s in tight pleather pants, a tiny top, her hips swaying to the music, and her long hair covering her face; it comes as a shock that she’s so young when her face is revealed. In a key scene, a member of the group picks up a condom off the street and starts blowing into it like a balloon, unaware of what she’s touching. At the same time, the girls wear tight clothing, often with low necks and bare midriffs, and perform increasingly sexually suggestive choreography. Despite many closeups of the girls’ bottoms as they dance, Doucouré avoids any kind of leering gaze, instead celebrating the girls’ rhythmic athleticism with a weary eye to how problematic this could be.

Unfortunately, Doucouré’s exploration of what’s driving the girls to want to present as sexualized adults so young is undercooked. Certainly, it’s partly curiosity, and there’s a great scene in which Amy watches the rear ends of a group of women in her building, shot from her height, after being made fun of by her friends for having a non-existent derriere. We also sense that Amy’s father may have taken a second wife to satisfy sexual desires, but since this is never made explicit, it’s unlikely Amy understands this.

Despite its flaws, Cuties proves that Doucouré has a keen eye for keeping us in the children’s perspective, and that leads to some wonderfully nuanced moments. Amy first discovers her father is taking a second wife when hiding under her mother’s bed. Her grandmother is bullying her mother into making this news known, and we watch that power play occur through Amy’s eyes, in the way the grandmother’s feet push towards the mother and invade her space. When Amy’s mother cries, Amy cries, understanding her life is changing, but perhaps not what all the implications of that are.

Discover the films of Céline Sciamma

Through essays and interviews with Sciamma and her team, discover the inner-workings of Water Lillies, Tomboy, Girlhood, and Portrait of a Lady on Fire.