In Full Time, writer-director Éric Gravel transforms a week in the life of a working mother into a heart-pounding thriller. It puts us in her stressed headspace.

Éric Gravel’s second feature film Full Time premiered in the Venice Orizzonti Program in 2021. The film recently screened at the Edinburgh Film Festival, at which time it had not yet secured North American distribution. The film has since been released in Canada and the US.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

In Full Time, writer-director Éric Gravel transforms a week in the life of a working mother into a heart-pounding thriller. The film puts us in her stressed, subjective headspace. Laure Calamy (Sybil; My Donkey, My Lover, and I; Call My Agent) stars as Julie, a single mother of two. She lives in the suburbs and commutes to Paris to work as head chambermaid at a five-star hotel. Over the course of the week we spend with her, everything that could go wrong does go wrong. A nation-wide strike means public transit grinds to a complete halt, threatening her commute. Her latest attempt to land a job that fits her puts her in danger of losing her current one. Her nanny quits. She has to host her son’s birthday party that weekend. And her ex is late with his alimony payment, putting her in overdraft.

A week in the life of Julie

Full Time opens on Julie asleep in bed. The camera is almost tactilely close to her skin, and we hear her breathing. It’s the first and last moment of repose she has before her week from hell begins. Once she gets out of bed, she doesn’t stop moving, nor does the mostly handheld camera (lensed by Victor Seguin). The cutting (by Mathilde Van de Moortel) propels us from one scene to the next at lightning speed. Gravel first shows Julie hurrying through her morning routine — feeding her kids, making their lunches, listening to the traffic report. Van de Moortel’s cutting is so crisp that you’ll probably miss half the steps Julie takes on first viewing. She is already overwhelmed to the point that even we can’t take it all in at once.

A real-time look at the stressful life of a single mother

From the moment Julie drops off her children with their nanny, she starts apologising, negotiating, and making promises. She won’t be late to pick them up again, she swears. But as the nanny points out, Julie chose has to work in the city and live in the country. This means she must take her chances with the commute and often can’t actually keep her promises —especially when there’s a transit strike.

Julie’s current job is exhausting and clearly not paying enough. Early in the film, Julie receives harassing calls she gets from the bank; her husband’s alimony is late. She has a job interview that week for a market research role that could be a game-changer. But she has to call in every favour possible to not lose the current job she relies on. This is not her first attempt at seeking employment elsewhere, so she knows the new job may not pan out. As the week progresses, the tension from all of these stressors ratchets up until Julie hits a breaking point.

The film Full Time keeps us in Julie’s headspace

Throughout the film Full Time, Gravel keeps us close to Julie and in her frenzied headspace. She is in almost every frame. She’s never alone, whether she’s walking down city streets, waiting for the train, or eating her lunch. Gravel always shoots her within a crowd. The crowd’s sounds puncture any hope for calm, and their movement giving her and our eyes no chance to rest.

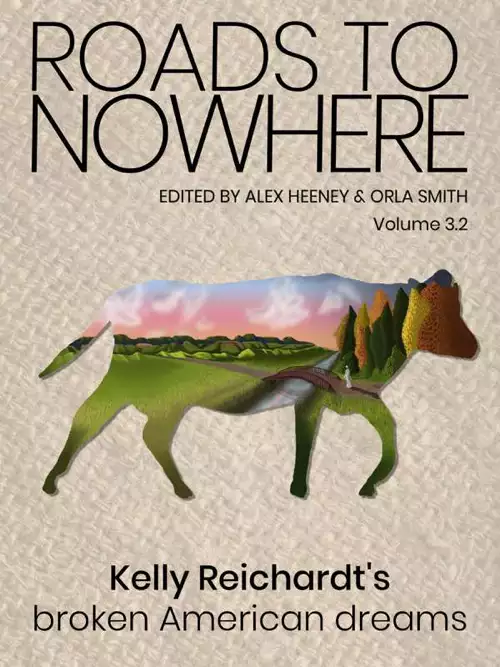

Kelly Reichardt’s films are also concerned with often invisible care work

Find out more about the first non-academic book about Kelly Reichardt’s work, the only book to include all of her films that have been released to date, and the only book about her process.

Even at home on the weekends, things are frantic. Her kids play a loud game of Hungry Hungry Hippos while she tries to wrangle together lunch. If Julie is still for a minute, the world around her isn’t. Gravel especially brings this to life through Julie’s daily commute, when we look out her window and see the moving landscape. Even this moment of potential rest is fraught with movement. It’s just another exhausting step on the way to the one hundred other things she has to do.

Van de Moortel’s strong editing is essential

Van de Moortel’s editing also prevents us from getting a reprieve that Julie doesn’t. She cuts off scenes abruptly, leaving us to fill in the ellipses. We’re always moving on to the next crisis, just like Julie. But instead of showing us key dramatic moments, we see the anxious build-up to and the frustrated come-down from them. For example, we don’t see Julie’s first job interview. Instead, we watch Julie in the waiting room, eyeing her competition: all men, all relaxed, all younger than her.

When she gets a follow-up interview, a good sign, we see her sitting uncomfortably waiting for her interviewer. The conversation doesn’t start off well. It might improve afterward, but Van de Moortel and Gravel deny us access to this part of the story. Instead, they cut to Julie beating herself up on the way out of the building. What matters is that Julie is terrified it went badly.

Julie may be an unreliable narrator

That also means that Julie might be an unreliable narrator, and we don’t get enough information to know by just how much. We see Julie getting increasingly frustrated that her ex isn’t picking up the phone. But is that because it’s a particularly stressful week, or because he’s regularly late to pay her alimony? Her best friend seems pretty relaxed about the ex and may even still be friendly with him, which suggests that Julie may be overreacting. Even her kids like his new girlfriend. He never shows up so we don’t know.

Julie seems convinced that she won’t lose her current job, even as she does dodgier and dodgier things to cover her tracks when she’s breaking the rules. We’re so close to her that we understand why she feels she has no choice but to make those decisions, but we also understand, from the start, that her position with her employer is already somewhat tenuous.

What the film doesn’t tell us about Julie is also key

There are also parts of Julie’s story that don’t quite line up. The job she’s applying to is actually a more junior position than the last time she held a desk job. Why did she stop working in her field? She tells the interviewer that she wanted to focus on raising her kids, after her last company went bust. But we know she’s been sending out CVs for years to no avail. The interviewer notes a four-year gap in her CV; we know she split with her ex at least six years ago. We also surmise that she must have been working at the hotel for several years — but not how many years — to have reached the top of the chambermaid hierarchy. Her story to the interviewer is clearly a calculated lie, but we don’t quite know how much of the truth she’s concealing.

Full Time is about how stress can distort reality

Ultimately, though, whether Julie is a trustworthy narrator or not doesn’t matter, because the film is more about how easily her reality could get distorted. Smartly, Gravel contextualises Julie’s meltdown as a product of larger systemic problems. This isn’t about bad choices that Julie is making. It’s about a world where all the choices are bad choices. The reason her life is going up in flames this particular week is because there’s a nationwide strike (and protests) against working conditions with not enough pay to match the rising cost of living.

Her personal compromises in the face of those issues — living in the country to give her children a more idyllic upbringing with more space while she commutes to work — are also what leads to her downfall. Because suddenly, transit is not reliable. Her difficulties at work, meanwhile, are because everyone is terrified of giving an inch to help Julie — her boss, her coworkers — lest they pay the price with their own job that they also desperately need. And we know those fears are justified, because that fear is part of what’s making Julie act erratically.

Laure Calamy shines in the film Full Time

Full Time, which deservedly won the Venice Orrizzonti awards for both Best Actress (Laure Calamy) and Best Director (Éric Gravel), is one of only a small number of films (think Leave No Trace, 45 Years, The Messenger) where the director and actor are working in perfect sync. Gravel’s directing choices rely on Laure Calamy’s terrific performance, and the strong performance really comes through because the direction is designed to support it at every turn. Key to this symbiosis is Gravel and Van de Moortel’s choice to allow quiet moments with Calamy to stand in for more conventional dramatic material. They let us notice her darting eyes, heavy breathing, and panicked looks.

Adjusting to Calamy’s rhythms

The whole film adjusts to fit Calamy’s, and thus Julie’s, rhythms. Seguin’s almost constantly moving camera moves at Julie’s speed. If she’s running, the camera work gets frantic and jagged to keep up. If she’s in a moment of reprieve, the camera slows down. Gravel lets the tension in the scene come from Calamy’s body language. As Julie works with her body for a living, Gravel is also highly attuned to Calamy’s body language. We’re constantly watching her do the work of keeping her life together: putting the kettle on, taking food out of the oven, running the bath, fixing the boiler, washing up the sink. The speed and vigour with which Calamy carries out these domestic tasks always reveals where Julie is at emotionally.

Even Irène Drésel’s highwire score — which works similarly to, if more subtly than, Hans Zimmer’s Dunkirk score — was added and perfected after Van de Moortel and Gravel had finished the edit. Gravel wanted to make sure the film was moving at Julie’s rhythm so the score could follow that, too. It also ensures we’re always completely emotionally with Julie, rooting for her, and stressed with her.

A nail-biting, stressful thriller

Indeed, I haven’t been this stressed out for the characters while watching a film since Sam Mendes’s 1917, a war thriller set in real time. 1917 and Dunkirk feel like particularly good touchstones for comparison here because they are both adrenaline-fueled rides, and so is Full Time. We’re used to going to the movies to watch men do conventionally stressful male tasks – like fight a war — but the care work that women so often do is rarely acknowledged as equally high stakes and stressful. Emotionally, Julie is in the trenches, with all the confusion, stress, and disorientation that implies.

Full Time serves as a welcome entry into the canon of films about rendering women’s invisible work and stressors visible, alongside films like The Assistant, Proxima, and Noura’s Dream. But where a film like The Assistant works on the low key dread of a million papercuts, Full Time makes Julie’s mounting everyday stress fully palpable. Indeed, its lack of subtlety about this is one of its strengths. That’s partly because Julie has lost all perspective. But it’s also partly because highly necessary and underappreciated care work that women predominantly do is stressful. It deserves to be placed in the same genre as a more conventional male job, and thus deserves the thriller treatment. With Full Time, Gravel turns the horrors of commuting into a gripping, emotionally wrenching story that connects Julie’s problems on the micro level to the nation’s problems on a macro level — all without ever getting didactic.

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch great films like Éric Gravel’s Full Time at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter stay informed about great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.

Click here to subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter.