Alex Heeney looks at the performances, costumes, and blocking in the Coen Brothers’ glorious Hail, Caesar and how it was heavily influenced by Golden Age Hollywood musicals.By returning to mine an earlier age, the Coens provide a rare vehicle for today’s stars.

The Coen Brothers’ Hail, Caesar is a glorious, hilarious tribute to the Golden Age of Hollywood. With its very own Esther Williams (Scarlett Johansson), Carmen Miranda (Veronica Osorio), and Gene Kelly (Channing Tatum), it’s got all the stock characters and genres of classic cinema. Even Roger Deakins’ 35mm cinematography mimics old movies, framing the action head-on as if filming a stage. But Hail, Caesar isn’t just a nostalgia-fest. By returning to mine an earlier age, the Coens provide a rare vehicle for today’s stars. Because the characters track so clearly to historical figures, it invites comparisons that the sterling cast manages to live up to.

Though it only contains three song or dance numbers, Hail, Caesar is a musical at heart – and like so many musicals, the film is an anthology, too. By following the travails of studio head Eddie Maddix (Josh Brolin) on a particularly trying day, we glimpse the filming of a historical epic, a synchronized swimming picture, a classic musical, a western, and a screwball comedy. Eddie’s own life resembles a noir picture, handling kidnappings, inconvenient pregnancies, and the unimaginable sin of sneaking cigarettes behind his wife’s back.

Even as the Coens pay homage to old movies, they’ve concocted something entirely original with its own rhythms, winks, and mastery of craft. Consider the scene in which Western star Hobie Doyle (Alden Ehrenreich) gets plopped into a drawing room drama. A minute ago Hobie was doing handstands on horses, but a comedy of manners is no place for this cowboy — he’s still walking with his legs bowed. It’s straight out of Singin’ in the Rain, but the scene becomes a screwball comedy as Hobie tries desperately to please his director, the perplexingly named Laurence Laurentz (Ralph Fiennes). In a performance of subtle comic brilliance, Fiennes looks down on Hobie as he whispers clipped directions with barely-concealed frustration.

The Coen Brothers deliver a gem in Channing Tatum’s homoerotic tap dance sequence: the musical number I’ve been waiting for since Magic Mike. The Coens cram callbacks to practically every Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire musical into this three-minute little ditty about sailors On the Town who are dreading heading back to sea. Referencing one of Astaire’s favourite props, Tatum dances on discarded nutshells. The staircase to the bar they’re in looks like the one from “Stepping out with My Baby” in Easter Parade. And the bar stool choreography is straight out of Singin’ in the Rain.

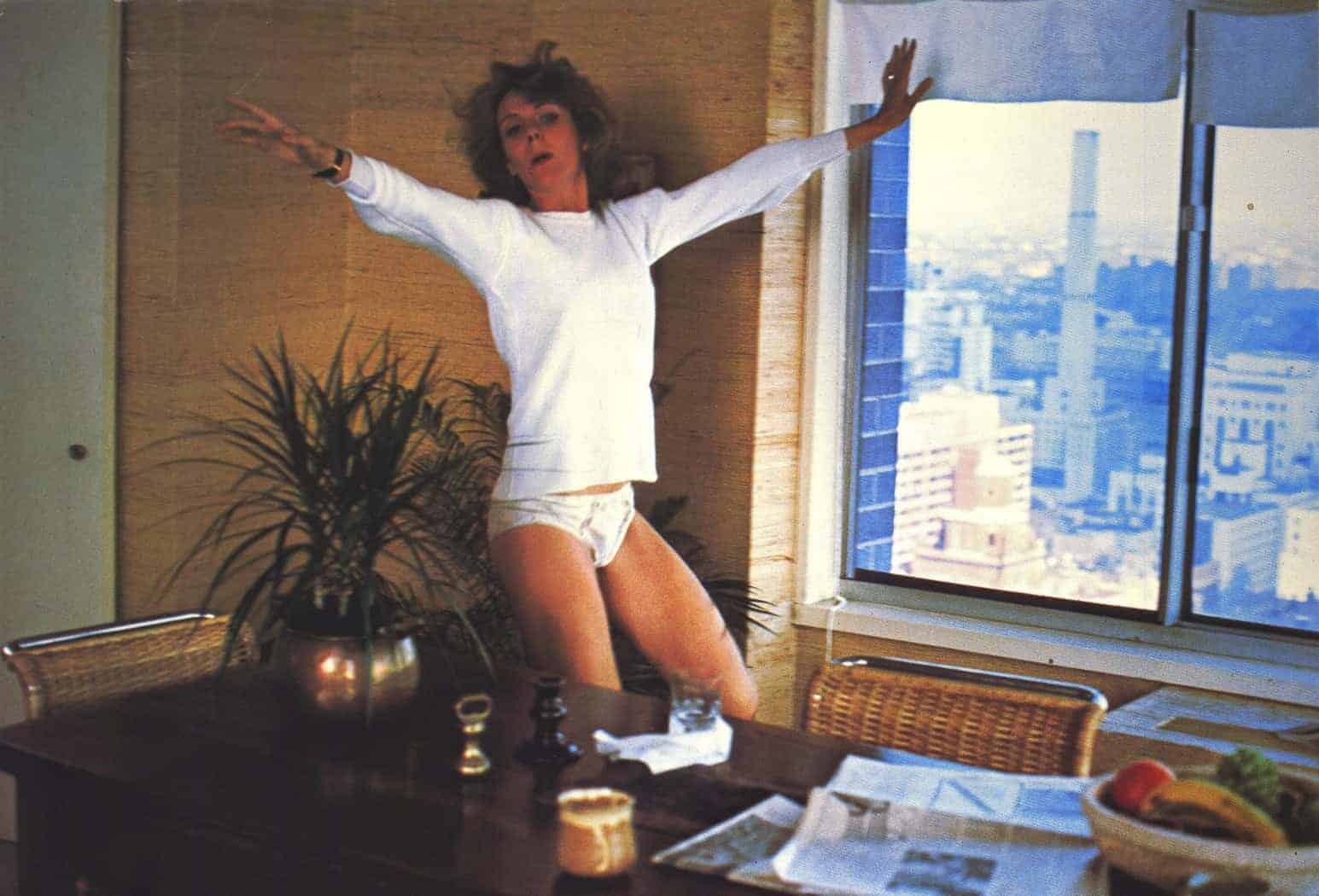

Whereas in Golden Age cinema, costumes were little more than an extravagant fashion show, designer Mary Zophre delivers fabulous outfits that accentuate the characters’ eccentricities. Eddie’s secretary (Heather Goldenhersh) rushes around to keep up with him with small, tiptoeing steps, hobbled by her confining tweed skirt suits. Tilda Swinton’s twin gossip reporters wear dramatic hats finished with protruding, razor-sharp feathers — a reminder that they’re poking around. DeAnna Moran’s (Scarlett Johansson) sparkly green mermaid suit might have been pulled straight from Esther Williams’ wardrobe, tiara included.

The best wardrobe gag is Baird Whitlock’s (George Clooney) ridiculous Spartacus-style centurion costume, which he’s wearing when he’s drugged and kidnapped. He wakes up on a lawn chair in a beachside mansion to find his captors are a group of bookish communist screenwriters, unhappy with how they’ve been compensated. Slouching in a parlour eating finger sandwiches, Baird looks increasingly goofy as we realise he’s basically wearing a leather mini-skirt and ballet slippers. The longer he’s there, the sillier he looks — until he finally becomes a literal card-carrying communist himself.

Although the Coens’ absurdist plot and whip-smart dialogue anchor the comedy, it’s the actors’ movement and voice work that fuel Hail, Caesar. No-one ever misses a mark, no matter how difficult the stunt. As Baird Whitlock, Clooney speaks in a loose, almost drunken drawl, which sounds all the more foolish once he’s drunk the Communist Kool Aid. Hobie’s rough, Western voice is completely at odds with the cultivated mid-Atlantic accents of the cast who actually belong in Laurentz’s picture. Fiennes’ refined British tones, polite manner, and subtle facial expressions allow for extra zings when his patience is tried — or finally used up, with a magnificent whack of the hand.

While the Coen Brothers’ previous film, the musical Inside Llewyn Davis, was a monochromatic world of poverty, dirt, and wet feet in a cold winter, Hail, Caesar gives us a colourful feast full of excess and fun. Just like the films that got us through the Great Depression and the post-war years, Hail, Caesar is a joy machine. There are a few lulls, mostly regarding Eddie’s existential career crisis, which doesn’t have the pizazz of the other subplots. Then again, it wouldn’t be a musical if you couldn’t complain about a bit too much plot and not quite enough song and dance.