Gillie Collins talks to Jenni Olson about her 16mm film essay, The Royal Road, a meandering story about unrequited love told through the linear progression of California’s El Camino road.

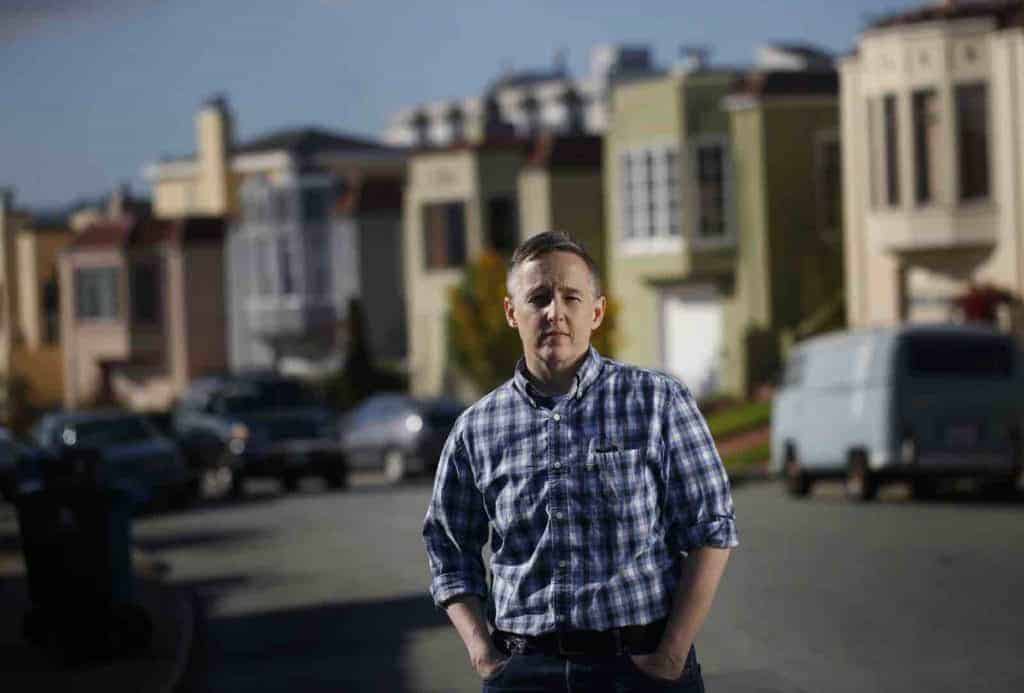

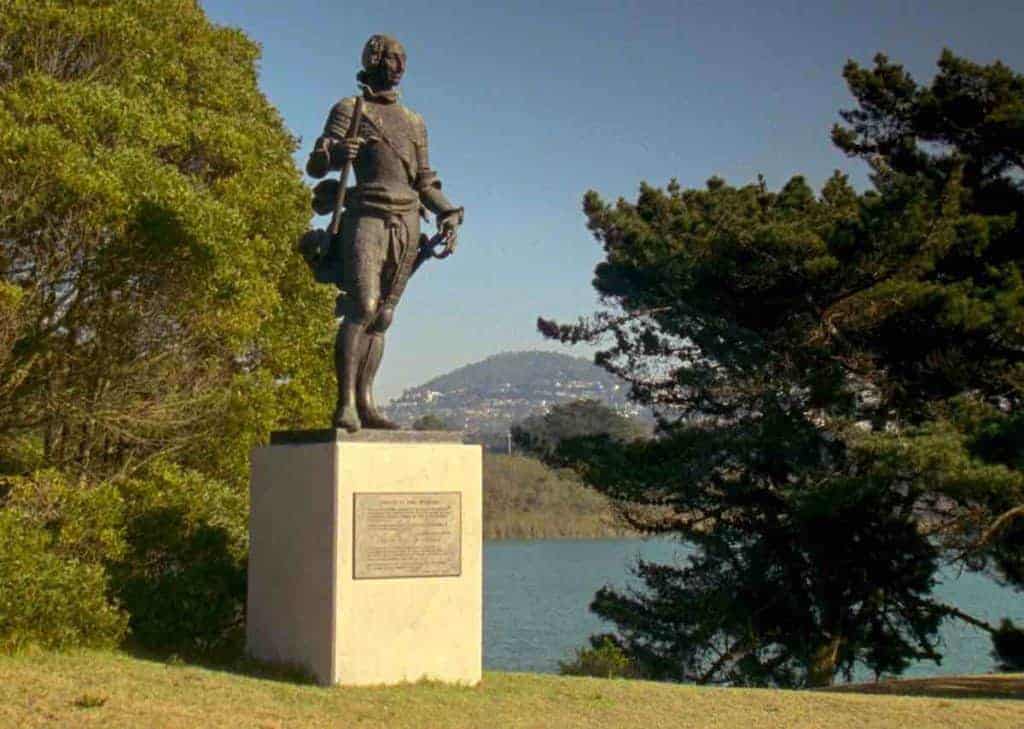

How do you tell a love story that never begins or ends, completely? In The Royal Road, queer film scholar Jenni Olson explores her lifelong attraction to women who don’t love her back. Through a series of 16 mm landscapes, the movie tracks Olson’s journey from her home in San Francisco to her beloved’s doorstep in Los Angeles. Meanwhile, in a matter-of-fact voiceover, Olson discusses nostalgia in Vertigo, the catharsis of fiction, and the politics of (mis)remembering California’s colonial history. The ground she covers is more psychological than geographical; by the end, we feel we know the “real” Olson, her obsessions and strength.

On the phone, Olson and I discussed the power of experimental film to upend aesthetic expectations and invite viewer introspection. The Royal Road, which premiered at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival, is now available online and on DVD.

Seventh Row (7R): Promotional materials for The Royal Road refer to the film as a “cinematic essay.” What does the term mean to you?

Jenni Olson (JO): I have always been trying to decide what category my work falls in. It’s documentary but obviously more complicated. It’s experimental, but that doesn’t really do it justice. It’s hybrid filmmaking, but that’s kind of abstract.

People know what a written essay is. They expect that it comes from a point of view, has a few different topics, and that the writer has something to say. I also think of [The Royal Road] as stream-of-consciousness. I’m rambling about all the different things that I’m interested in. It’s also poetic, to a degree. I’m speaking in first-person, in a confessional monologue format.

The other category that it falls in is landscape film, which is a very obscure, tiny sub-genre of experimental documentary. [The film] consists entirely of 16mm static landscapes. [You get a] sense of this character, this figure, wandering the landscapes, talking about where we are — but half the time [what she says] isn’t directly connected to what you’re seeing.

7R: Roads are so linear, but this film seems to be nothing if not meandering. Why did you focus on a road? Why follow El Camino Real, in particular?

JO: I wanted to shoot in both San Francisco and LA. At some point, I thought of [the road] as a structural device. The plot, if there is one, is just the line: “I will follow the railroad to her door.”

There is this sense in which nothing actually happens — which, you know, I’m very proud of. It’s hard to do that….You come out of those action movies [in which] all these things happened and, yet, who cares? Things exploded. Everything exploded. And it was like eating M&M’s.

7R: In The Royal Road, personal and public histories are woven together. You discuss your romantic history alongside the history of California and the history of Hollywood cinema. Why did you feel like those strands of the past belong together?

JO: The organizing principle is this single voice. The first-person voice is, part of the time, me. Other times, [it’s] a fictionalized version of myself. I pretend…to be a fictional character as a way to be vulnerable and speak [about] pining over unavailable women. I’m [also] interested in all these other topics, the landscape of California, the history of California. [The voice] is simultaneously me and not me.

7R: The beginning of the film includes a quote by Michel Chion: “‘The word ‘voiceover’ designates any bodiless voices in a film that tell stories, provide commentary, or evoke the past. When this voice has not yet been visualized — we get a special being, a kind of talking and acting shadow.’” Why did you choose to keep the narrator disembodied throughout the film?

JO: I was drawn to the format of landscape filmmaking. I like how it works: viewers project themselves into the space. You have an intimate and unique connection with the character [you’re] hearing — but really, you’re connecting with yourself because you are alone in that landscape.

That’s the other thing: there are no people in the film. Over the course of 65 minutes spent in this quiet landscape, you go through something that is about you.

This is one of the unique things about experimental film, in general. It works in a completely different way than conventional narrative. In conventional narrative, you have to say, “I’m going to have my experience through that character.” Of course, there are times where you are thinking about your own personal experience — but not in such an intense way. [In The Royal Road], you have to come into the film. It’s a much more dynamic relationship between the viewer and the film.

7R: I watched The Royal Road once on my own and once with my friend. I was acutely aware of how we must have had extremely different experiences of the film. I wondered what my friend was thinking.

JO: One of the things that people seem to respond to most deeply is that [the film] is a very intimate experience. The voiceover is very vulnerable. I say certain things that we actually want to hear other people saying …to feel a little less alone. It’s cathartic, which is the one of the most valuable things about art. It allows us to connect with our own feelings and to connect with our own deeper parts of ourselves.

7R: Why are you drawn to using 16mm film?

JO: Increasingly, [16mm film] has emotional qualities that evoke the analog, [as opposed to] the digital…which in turn evokes not just literally “long-ago” or “old-fashioned” but, particularly for me and my generation, a younger time in our lives, a simpler time. Actually, a less distracted time.

I literally try to recreate a less distracted experience in the film. I’ve composed the shots so that there are no billboards, no advertising, no bright yellow crosswalks. [Nothing that] is yelling at us: “Buy this!” or “Make this decision!” Watching this film, you spend 65 minutes, [you enter] a peaceful environment that, in and of itself, is nostalgic, [like] the world…10 years ago. I confess, I miss that.

[But] I’m not just trying to say, “I wish it were like that again.” I’m trying to say, “Let’s think about nostalgia in relation to who we are and where we are right now.” There’s a reason we hunger for it — it makes us feel more connected to ourselves.