Pakistan-born, Toronto-based filmmaker Haya Waseem discusses her TIFF short film Shahzad, Seventh Row’s pick for the best Canadian short at the festival.

Born in Pakistan, raised in Switzerland, and now based in Toronto, writer-director Haya Waseem epitomizes the Torontonian as a citizen of the world. Her short film Shahzad will screen in Short Cuts Programme Five at the Toronto International Film Festival, and it was Seventh Row’s pick for the best Canadian short at the festival.

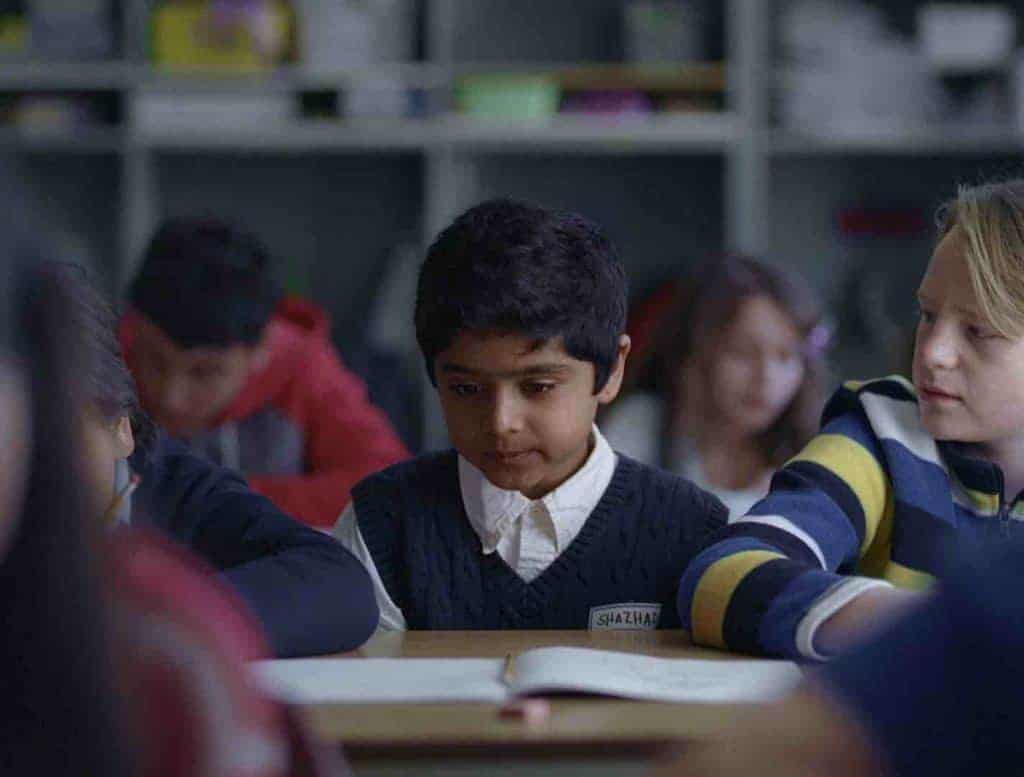

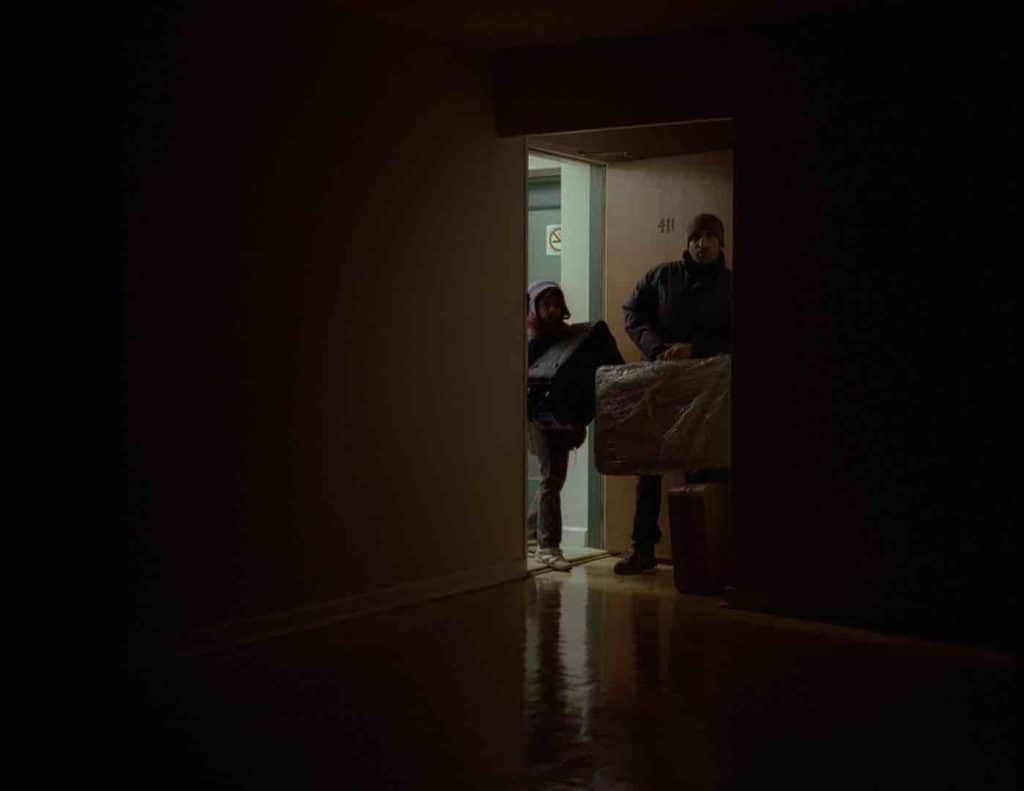

The film follows the eponymous Shahzad, a young Pakistani boy who has just moved to Toronto, as he makes friends, integrates into Canadian society, and finds his home with his father Iqbal an increasingly alien place. Waseem talked to The Seventh Row by email about the genesis of the film, the Canadian immigration experience, and the important of making Canadian films in recognizably Canadian settings.

SHAHZAD from Haya Waseem on Vimeo.

Seventh Row (7R): What was the genesis of the idea for the film?

Haya Waseem (HW): I’d been reflecting on my experience of moving to Switzerland and later to Canada as a child — remembering how I’d made friends, how I got used to my new environment, how I learned the language etc. As I thought about that, I suddenly wondered what my parents would have been going through then. I had never thought about that and realized I never expected that they would be going through changes and events of their own. That formed a base for Shahzad, this exploration of change for a child and, through his perspective, the change in a parent.

There was also an image I’d come across a long time ago of a man with a goatee wearing red lipstick and blue eye shadow looking right into camera.

Somehow, the convergence of that base for an idea and that image connected, and Shahzad was born.

7R: I loved the way you used rituals like the daily dinners to show the changes in the family and assimilation. How did you think about structuring the film?

HW: Thank you! I was drawn to the idea that this father and son are distant but still care deeply about each other. Even though they may not communicate openly, Iqbal never fails to ask Shahzad how his day was; this is the only opportunity he has to gauge his son’s state. It becomes about the mannerisms and the tone in which Shahzad responds, that Iqbal has to understand how Shahzad is feeling.

The ritual of the dinners gave me a base to show Shahzad’s growth: how withdrawn he feels after his first day, how excited he feels about the next, and ultimately, how he reacts to change. The rituals served as a reference for change and growth. Every time we came back to it, we saw how our characters are changing.

7R: The immigration experience in Canada is such a quintessential but under-discussed/undertold story. Was there anything in particular that you wanted to tell that you felt hadn’t been told before? Or tell differently?

HW: Yes! A lot of people wondered how easy it was for Shahzad to make friends and integrate into Canadian society, and that was my experience when I moved, too. I had no trouble finding a [new] ‘home’. Where things can be challenging is within your own [home]; whether it’s old values, or certain principles you can’t let go of that may not hold much weight or relevance here. So for me, it was interesting and important to explore an immigrant story where the antagonists weren’t in the external society but rather, changes and dogmas within the family.

[clickToTweet tweet=”I find it incredibly fortunate for us to have such a multi-cultural city, and we are accepting. ” quote=”I find it incredibly fortunate for us to have such a multi-cultural city where anyone and everyone co-exists, and we are accepting. “]

I am surprised — I understand — but I am surprised to learn how many people would expect Shahzad to be bullied and for the story to be about the hardships of integrating into Canadian society. But that simply wasn’t my experience. It certainly isn’t the experience of many other immigrants I know. Often, the conflicts spark from old inhibitions and cultural values that held weight in their country of origin and don’t necessarily apply here. When those values are imposed, that’s where conflicts might occur — from within rather than outside.

I wanted to tell an immigrant story from an internal point of view rather than external. This is a story about two immigrants, yes, but underneath that, it’s simply a story about two people who are changing.

7R: The film felt and looked like Toronto — helped by the multi-racial, multicultural cast. How did you think about setting, and how important was that to the storytelling?

HW: It’s so bizarre to me that it isn’t more a part of Canadian and Toronto cinema. I find it incredibly fortunate for us to have such a multi-cultural city where anyone and everyone co-exists, and we are accepting. At least, that is what I have seen for the past six or seven years that I have lived here. Compared to other parts of the world where I have lived or experienced, Toronto — and Canada — has definitely been one of the most accepting places.

[clickToTweet tweet=”I wanted, through SHAHZAD, to show how welcoming, even in its cold winters, Toronto can be.” quote=”I wanted, through Shahzad, to show how welcoming, even in its cold winters, Toronto can be, if you’re open to it.”]

Toronto has played a big part in my storytelling. My short documentary, Familiar, is essentially a love letter to Toronto and the beautifully diverse people it holds. With Shahzad, I really wanted to shed a light on Toronto the same way I saw it. Everyone may not see it the same way I do, but I see Toronto as a safe, welcoming place where you can be seen and heard if you allow it.

I wanted, through Shahzad, to show how welcoming, even in its cold winters, Toronto can be if you’re open to it. Shahzad is young and open and allows the city and its people to hold him. I wanted that to be the light in which the city is portrayed. Even the little stop sign that Shahzad jumps up and high fives after his invite to his friends house and the railing he runs his hand across, he is becoming friends with his environment.

It simply boils down to my experience; as an immigrant, I have felt at home in Toronto. I have felt the warmth of its people, and I am grateful. That’s why the city plays a part in my films, because it contriubutes to my freedom of expression.

7R: The scene where Shahzad finds his father in his room putting on makeup is shot with such tenderness and empathy. How did you think about how to create that reveal?

HW: I think it was an instinct. I can’t remember how it came about, but I know that scene was always that way in my mind, and I never poked it around too much. I wanted to keep that scene through the crack of the door. Something about the father being caught in his reflection, then turning around to face his father… It was always that way, and it felt right for the characters. Often, such circumstances follow a conversation, or a confrontation, but I was adamant in maintaining a sense of stillness between the two characters.

I also think the moment lends itself that way because Shahzad isn’t judging his father. It’s more of a ‘widening of perspective’ for Shahzad rather than an instant reaction of judgment. I think the main instinct was to maintain a gaze through the door, for Iqbal to be seen through his reflection, and to maintain a stillness in that moment.

[clickToTweet tweet=”We chose 4:3 aspect ratio…that Shahzad might experience his environment with tunnel vision.” quote=”We also chose 4:3 aspect ratio based on our characters: this notion that Shahzad, and kids that age, might experience their change of environment almost with tunnel vision, concerned about their integration and not necessarily the changes around them.”]

7R: The scenes at home are mostly calm and sedate while the scenes at school are more often handheld. How did you develop the aesthetic for each of these locations?

HW: Yes, that was established early on with my cinematographer Christopher Lew, with whom I collaborate with beyond just images, but on themes and story and philosophy. He and I very much built Shahzad together, I thought of the characters, and Chris built a world around them. But the aesthetic of the school and the apartment were established when we communicated about how Shahzad reacts to both environments. When Shahzad opens up at school, so too does that camera. When Shahzad is at home, however, the rigidity of his relationship with his father, and the distance, contributes to the wide, static shot approach for the dinner scenes.

When Shahzad first arrives in his classroom, the camera is quite still, as well, but as he opens up, the camera loosens up and explores the environment freely as Shahzad does. So for us, it was a very simple character-based choice that lead to the aesthetic of the film.

We also chose 4:3 [aspect ratio] based on our characters: this notion that Shahzad, and kids that age, might experience their change of environment almost with tunnel vision, concerned about their integration and not necessarily the changes around them. We thought 4:3 would emulate that better than a wide screen approach.

Shahzad screens in Short Cuts Programme 5 on Sun., Sept. 11 at 7 p.m (Scotiabank) and Fri., Sept. 16 at 3 p.m. (Scotiabank).