In Seymour: An Introduction, Ethan Hawke follows his friend. former concert pianist Seymour Bernstein, for an intimate, inside look at the process of making art, its rewards and struggles, and an ode to a great teacher.

Essays

Merchants of Doubt: an inside look at the climate change denial industry that doesn’t delve deep enough

Merchants of Doubt takes an in-depth look at how the same public relations experts — these “Merchants of Doubt” — who helped tobacco companies persuade the world, in the 1950s and 1960s, that cigarettes weren’t harmful to health, even though the tobacco companies had done their own very good scientific studies that proved the opposite, were […]

Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem: Will she ever get her Gett?

Ronit and Shlomi Elkmbetz direct this grueling, heartbreaking courtroom drama. Gets: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem, which follows a divorce case over five years, all from within the courtroom itself.

Great Movies: Oslo, August 31st and loneliness in the city

Joachim Trier’s brilliant and moving Oslo, August 31st is as much about its protagonist as it is about his generation and his city. Listen to our podcast on Oslo, August 31st here.

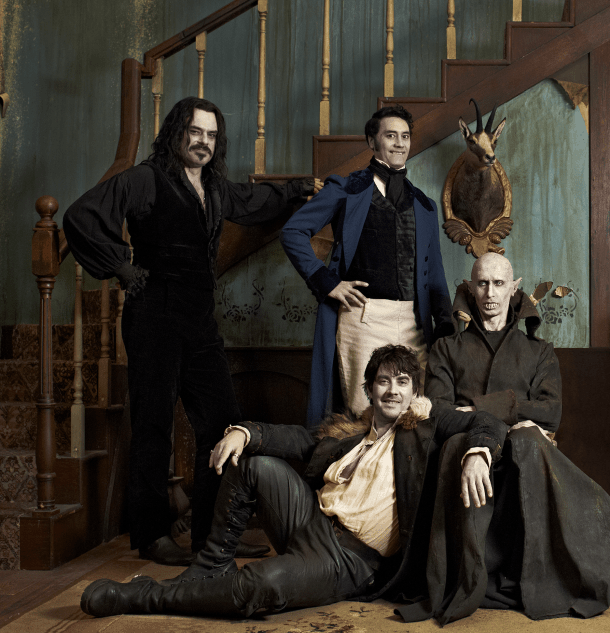

Review: What We Do in the Shadows is a hilarious vampire mockumentary

“Vampires have had a really bad rep. We’re not these mopey old creatures who live in castles — well, most of us are, a lot of us are — but there are also those of us who like to flat together in really small countries like New Zealand.” With these words, the 18th century dandy […]

Don’t be fooled by the title, Fifty Shades of Grey is Anastasia’s film

Fifty Shades of Grey is far more interested in Anastasia’s thoughts and conscious decisions than in giving Christian even a semblance of a personality.