Jennifer Peedom discusses the making of her terrific Everest doc, Sherpa, the first documentary to be told from the Sherpa’s perspective.

Creative Non-Fiction

Creative Non-Fiction is often a more appropriate word for describing innovative forms in documentary filmmaking, which go beyond mere information dump. Here you'll find reviews of films that are pushing the form and interviews with non-fiction filmmakers about making non-fiction works of art.

88:88 is a formal and ideological marvel **** 1/2

88:88, an emphatic statement on poverty, debuts an exciting, radical new voice in cinema: Winnipeg-based Isiah Medina. The numbers ‘88:88’ flash across alarm clocks when electricity goes out: The accurate time is replaced by these place holders and time essentially stands still. The central philosophical meaning of 88:88 in the film is one of stasis, and how that stasis caused by poverty subjects people to a minimized life.

TIFF15: Leanne Pooley discusses her animated war doc 25 April

Leanne Pooley’s boundary-pushing animated documentary 25 April follows six New Zealanders’ experiences during the World War I Battle of Gallipoli in 1915. The battle was an important part of New Zealand history because of how poorly the British treated their colonial forces: underquipped, under-supported troops were deployed in Turkey for what ended up being a pointless […]

Gillian Armstrong talks Women He’s Undressed

Director Gillian Armstrong discusses Australian costume designer Orry-Kelly and her gorgeous documentary about his life and craft — with a side of Cary Grant and Bette Davis.

TIFF15: Sherpa is an inside look at the Nepalese people who make climbing Everest possible

With Sherpa, Australian filmmaker Jennifer Peedom revisits the story of Everest, but in present day and from the Sherpas’ perspective instead of that of the Westerners who hope to conquer it.

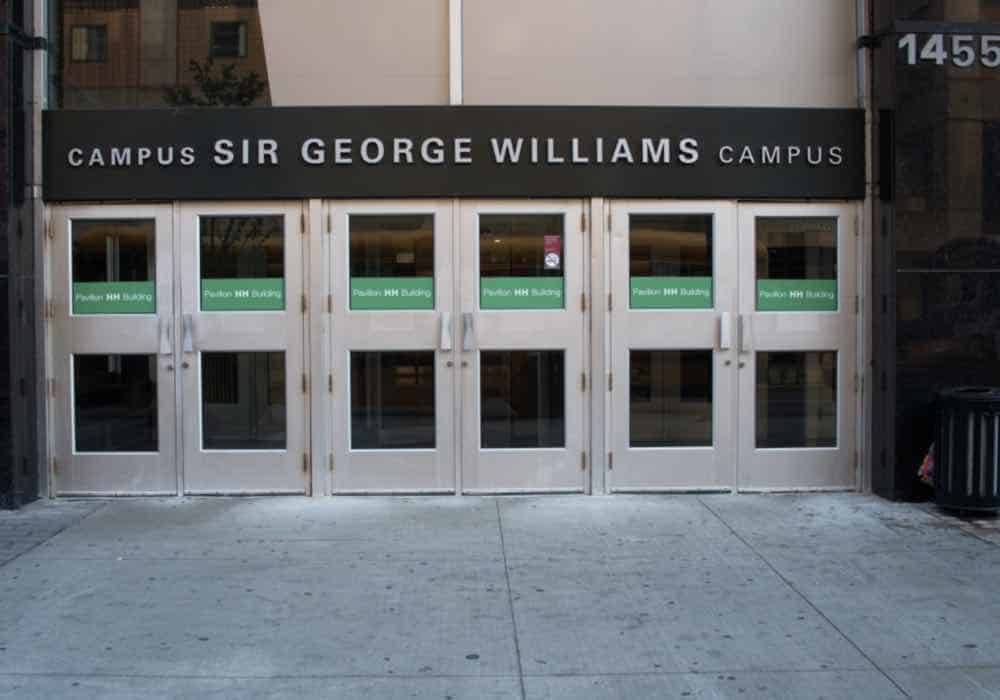

TIFF15 review: NFB history doc Ninth Floor sheds light on our racial biases

Mina Shum’s taut and accomplished documentary The Ninth Floor is an extremely important film about racial discrimination in Canada. Not only does it retell a crucial part of Canadian history that never made it into the history books I studied in school, but the incident it depicts has continued relevance today. The title refers to the […]