We’re in an age of mass extinction. For centuries, you might expect one species to go extinct per year, but thanks to human activities, these numbers have increased by orders of magnitude. Director Louie Psihoyos’ Racing Extinction aims to not just manufacture outrage about this fact, but to create a sense of wonder at the natural […]

Documentary

TIFF15: Leanne Pooley discusses her animated war doc 25 April

Leanne Pooley’s boundary-pushing animated documentary 25 April follows six New Zealanders’ experiences during the World War I Battle of Gallipoli in 1915. The battle was an important part of New Zealand history because of how poorly the British treated their colonial forces: underquipped, under-supported troops were deployed in Turkey for what ended up being a pointless […]

Gillian Armstrong talks Women He’s Undressed

Director Gillian Armstrong discusses Australian costume designer Orry-Kelly and her gorgeous documentary about his life and craft — with a side of Cary Grant and Bette Davis.

TIFF15: Sherpa is an inside look at the Nepalese people who make climbing Everest possible

With Sherpa, Australian filmmaker Jennifer Peedom revisits the story of Everest, but in present day and from the Sherpas’ perspective instead of that of the Westerners who hope to conquer it.

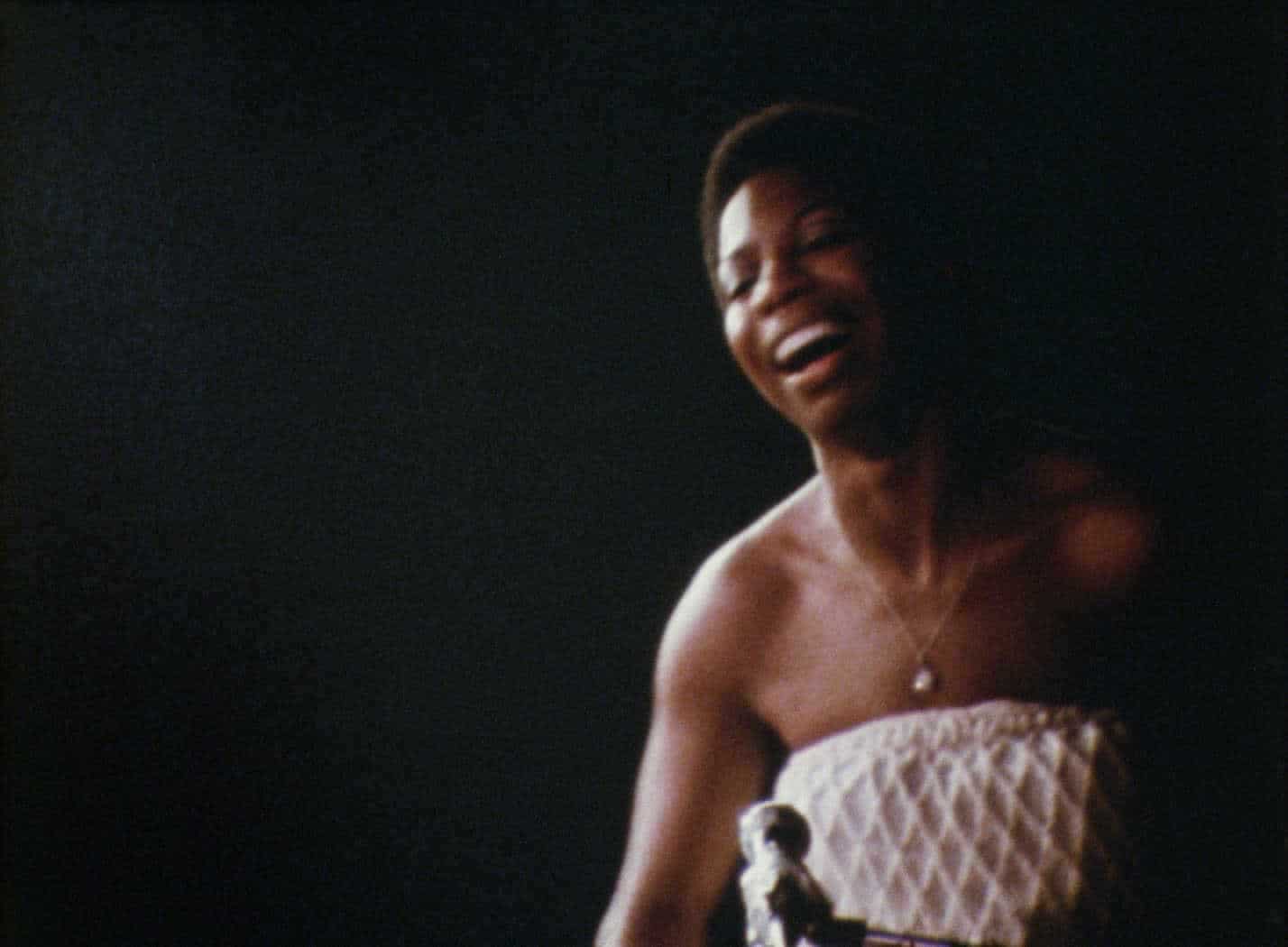

What Happened, Miss Simone? is all about the passion

Liz Garbus’ new documentary, What Happened, Miss Simone?, consists mainly of rousing historical footage of Simone’s concerts and interviews, while paying tribute to Simone’s achievements and illuminating the struggles in her life. Nina Simone wanted to become the first black female classical pianist to perform at Carnegie Hall. She had to settle for becoming a […]

Seymour: An Introduction: A moving portrait of the artist as a humble teacher

In Seymour: An Introduction, Ethan Hawke follows his friend. former concert pianist Seymour Bernstein, for an intimate, inside look at the process of making art, its rewards and struggles, and an ode to a great teacher.