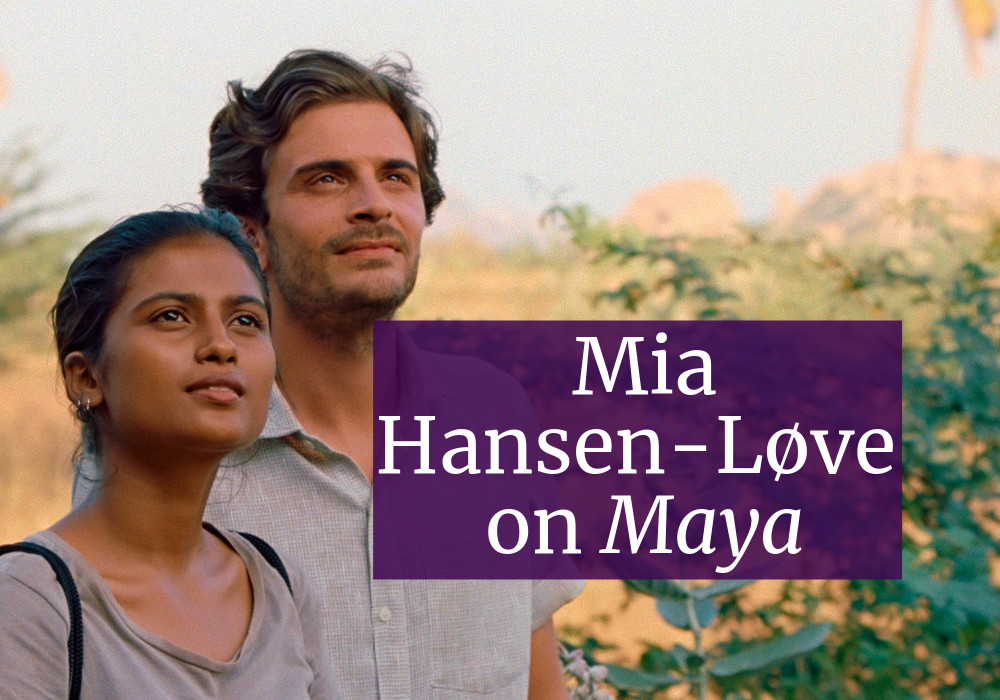

Mia Hansen-Løve tells us about her new film, Maya, her interest in people who stay in the shadows, her motivations behind choosing locations, the way she works with her actors, and much more. The film premiered at TIFF, where we talked to Hansen-Løve, and is screening at Rendez-Vous with French Cinema in NYC.

Rendez-vous with French cinema

Rendez-Vous with French Cinema 2019: Highlights

Here’s a look at some of the best films screening at the 2019 Rendez-Vous with French Cinema in NYC, including Premiére Année (The Freshman), Keep an Eye Out!, and Raising Colours. Every year, the Film Society of Lincoln Centre curates some of the best of French Cinema in the last year for the Rendez-Vous with […]

‘For me, cinema is where we can speak to our own fragility and vulnerability’: Mikhaël Hers discusses Amanda

Mikhaël Hers talks about his approach to tragedy in Amanda, which follows a young girl and her uncle as they reckon with the consequences of a terrorist attack. The film is screening in the Rendez-Vous with French Cinema festival at Lincoln Centre in NYC on March 9. If terrorist attacks are becoming more frequent in […]

Arnaud Desplechin: ‘Each character must have a mystery’

Arnaud Desplechin and star Mathieu Amalric discuss Ismael’s Ghosts, what they bring to each other, the bigger-than-life characters they create and play, and the secrets that they keep.

Julie Delpy talks colour and comedy in Lolo

Writer-Director-Actress Julie Delpy discusses her consummately entertaining new movie, Lolo, which is chock full of the same joie de vivre Delpy channels in real life.

Fatima is a tender look at making a home in a new land

Fatima meditates on language barriers and what it takes to become French.