In Steve James’s documentary Life Itself, we discover the story of Roger Ebert with enormously, who championed the movies as an empathy machine.

If you enjoy this review of Life Itself, a documentary about Roger Ebert, you may enjoy our book about documentary filmmaking.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

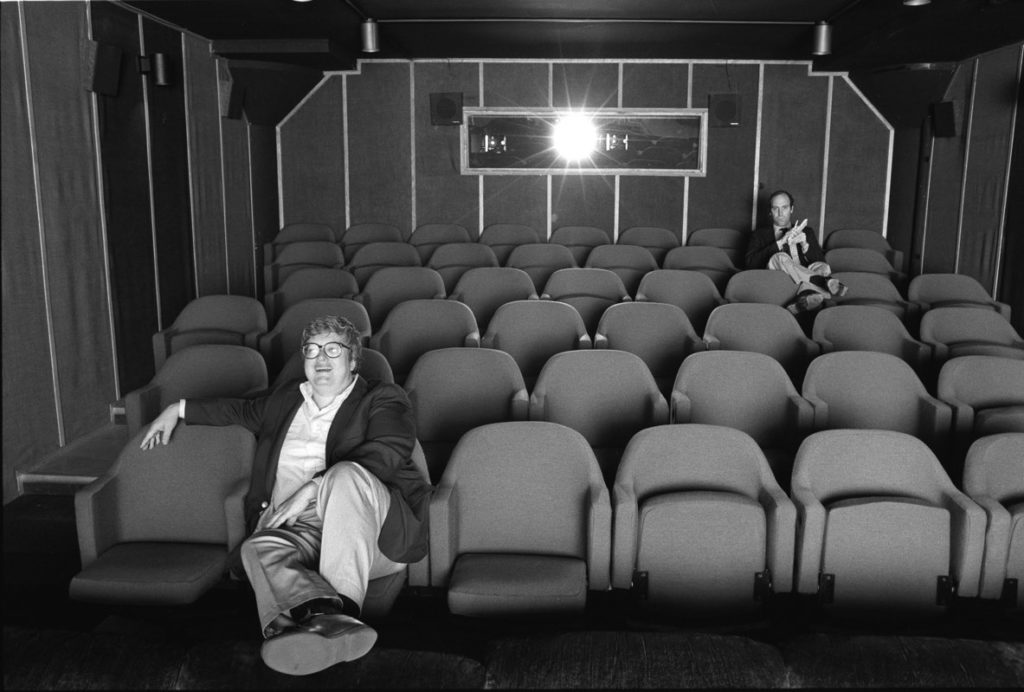

I grew up watching Siskel and Ebert and The Movies. It was a weekly ritual in my house, helping us decide what to see that weekend. The show struck something deep, and inspired me to start writing film reviews at a very young age: I was in grade 6 and I started my own magazine. It was through their television show that Siskel and Ebert became the world’s most powerful and influential film critics.

Ebert had been working at the Chicago Sun Times part time while he pursued a PhD in English, when its film critic retired, and he was appointed his successor. At the time, critics were often interchangeable: at the Chicago Tribune, they wrote under the nom de plume “Mae Tinee” (matinee). Of course, he was one of the people that changed all that, following in the footsteps of Pauline Kael: unfortunately, the debt he owes her, including the degree to which he was influenced by her, is not handled well in the film.

On their show, Siskel and Ebert championed work by unknown directors, launching the careers of filmmakers like Errol Morris and Martin Scorsese. The profound effect that Ebert’s encouragement had on these filmmakers is felt in the brief interviews with them: Scorsese nigh well breaks down remembering the tribute to him the pair held at the Toronto International Film Festival, which helped him to get back to work after being depressed. He also recalls the generosity and intelligence, which Ebert would give even his unfavourable reviews. Ironically, while Siskel and Ebert popularized and democratized film criticism with their show – and their trademark thumbs up/thumbs down rating system – they also perpetuated the false notion that films are simply either good or bad. The constraints of television prevented a more complex reading.

It’s with such contradictions and nuances that Steve James’s film tells the story of Ebert’s life and work. Ebert was at once firmly a man of the people – he remained loyal to The Chicago Sun Times, the working-class newspaper which gave him his start – and yet also cocky, arrogant, and pompous. He was professionally mature and socially immature: he went through a series of bad romantic choices before he finally met his wife, Chaz Ebert, at age fifty, who had a profound effect on his life and personality. He was a control freak and an alcoholic. And he had a love-hate relationship with his television sparring partner, Gene Siskel: they argued with bitter hatred and petulance, but they also, eventually, grew to share a deep respect for each other. As Siskel would say, “he was an asshole, but he was my asshole”.

“Life Itself” is the kind of film that reminds you why you love the movies and writing about movies. There’s a wonderful romanticism with which Ebert describes his initiation into the world of print media, helped along by the brassy, nostalgic, jazz age score. As a child, he delivered papers in his neighbourhood, and by the time he was fifteen, he had a byline in the newspaper. He got to keep his name in linotype, and he took to putting it to a stamp pad and stamping his name on everything. He recalls, “My parents eventually had to take it away from me. Everything was ‘by Roger Ebert.’” In college, at UIUC he ran the Daily student newspaper, where he spent the majority of his time. At every step, you get the sense of the thrill that seeing his name in print gave him, of reaching his readers, especially late in life, when his writer’s voice became his only voice. Because the film understands so well what it’s like to be a critic, the film will strike the deepest chord with us critics. But it’s as much a film about love, friendship, alcoholism, growth, family, death, and a life-long love affair with the movies.

In his Hollywood Star acceptance speech, which opens the film, Ebert describes movies as an empathy-generating machine. Throughout the film, you get the sense that they worked their magic on Ebert himself. The pompous self-assured guy that was the first film critic to win a Pullitzer was not the same man that would later marry a black woman, growing kinder and softer with age. The man who had no qualms about putting down the “Three Amigos” on the Johnny Carson show, while sitting next to Chevy Chase, is not the same man who would be the first in line at Sundance for an 8AM screening, on the last day, of a film by the then unknown filmmaker Ramin Bahrani who had personally emailed him to tell him about it. And it was Ebert’s evolving relationships with Chaz and Siskel that shaped him most, which James captures through interviews with Chaz and Siskel’s widow, as well as other professional colleagues.

Siskel passed away young from a brain tumour, and he kept it quiet while it was happening, something that devastated Ebert: he never got to say goodbye. Afterward, Ebert vowed that if he should ever become very sick, he wouldn’t keep it a secret, from his family or friends, and in the end, he shared it with his readers, too. It’s for this reason that Ebert encouraged James to capture all the excruciating details of his illness that are usually left behind closed doors: the painful process of suction, the exhaustion of rehab, and all the time in the hospital. James also captures Chaz’s worries and grief, getting raw emotion rather than after-school special tear-jerking. It’s impossible to hear her talk about the end of her husband’s life, and everything he meant to her, without choking up, but the film is never manipulative.

The film is at its least successful and interesting when it’s filling in obligatory biographical details, like Ebert writing the screenplay for “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls,” but it’s clear, by the end, that these need to be there to give a complete portrait of the man. In his book, “Life, Itself,” Ebert writes, “I was born inside the movie of my life…I don’t remember how I got into the movie, but it continues to entertain me.” Roger Ebert spent his life at the movies. Now, he’ll live on in a movie we can keep revisiting. It’s a loving tribute, which shows Ebert as he really was, the good and the bad, and above all, a man whose love of movies was infectious.

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch great films like Life Itself at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.