You’d be hard-pressed to find a more faithful screen adaptation of a novel than David Fincher’s film Gone Girl, which was also written by the book’s author, Gillian Flynn. From its pitch-perfect casting – Rosamund Pike as the icily sophisticated and gorgeous Amy, and Ben Affleck as her husband Nick, a man with frat boy charm and a punchable face – to its careful adherence to the plot of the book, Fincher’s direction and Flynn’s script have almost flawlessly translated the novel’s tone and devices into film language.

This taut, two-hour yarn, is part murder mystery, relationship drama, satire, outrageous comedy, and camp, but Fincher mostly makes them all fit together seamlessly, creating what is, above all, a highly entertaining romp. But much of the depth and intelligence of the novel gets lost in translation: the film is not the complex exploration of the performance of gender roles and identity that the novel was.

When the film begins, Amy Elliott (Rosamund Pike) and her husband Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) are living in a luxurious home in suburban Missouri where Nick grew up. After both lost their jobs as New York City journalists, and Nick’s mother got sick, they traded their Manhattan brownstone for a mansion that they never bothered to transform into their own home: its neutral colours and nonexistent wall art look like a staged home, not a lived in one. They used what remained of Amy’s trust-fund to buy a local bar for Nick and his sensible sister Margo (Carrie Coon) to run, which they named, rather self-consciously, The Bar.

Amy laid down no such roots, and just after the film begins, we discover she’s gone missing, after, the evidence initially suggests, a violent altercation, but it soon becomes clear that it’s not quite so simple. As the police – led by the clever Boney (a wonderfully commanding Kim Dickens in a pant suit) and her sounding board assistant (Patrick Fugit) – investigate her disappearance, Nick starts to come into focus as the prime suspect in the case.

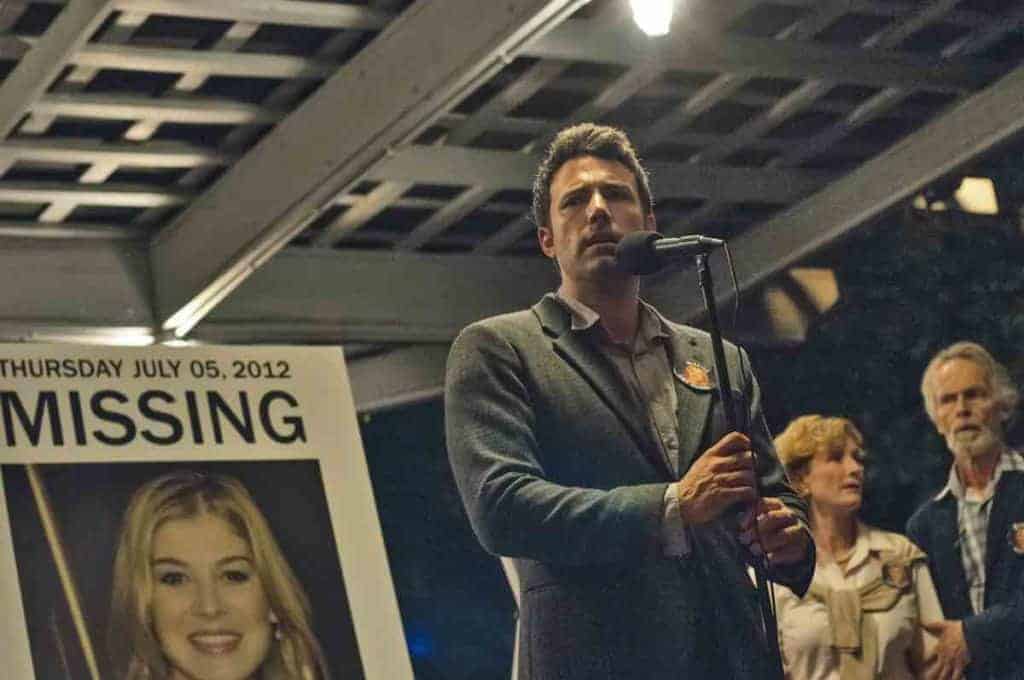

Nick’s problem is that he doesn’t know how to perform for the cameras. As soon as he informs Amy’s parents of what has happened, they rally forces to get as much media coverage for their daughter’s disappearance as possible. Nick, awkward and unsure of how to act the grieving husband, but desperate to be liked, makes the mistake of smiling for the cameras, at a press conference about Amy’s disappearance, while posing next to her photograph.

Inappropriate behaviour is Nick’s affliction. When first showing the cops around his home, the newly minted crime scene, he’s shockingly relaxed for a man whose wife might have been murdered. The book explained that Nick was deliberately putting on a show, trying to get the cops to like him, but the film is more ambiguous. We never get Nick’s inner monologue, but his behavior and the short depth of field in Fincher’s frames let us know he’s not to be trusted. We’re not sure why, and like the book, Flynn’s screenplay draws us in, to sympathize with Nick before recounting his sins: he’s been cheating on his wife with a twenty-year-old student for months.

As in the book, the film moves back and forth between flashbacks of the past, as recounted by Amy in her diary, and the investigation in the present, from Nick’s perspective. In the book, both were unreliable narrators and pathological liars of different flavours. Fincher captures this by playing with our genre expectation in the way he shoots Amy’s accounts of the past, as well as Nick’s story in the present.

When the film flashes back to what Amy perkily recalls as her meet-cute with Nick – the night they met at a New York party over impossibly clever banter, before sharing their first kiss in a paradisal sugar storm outside a local bakery – Fincher’s visuals serve up something more sinister. By using neutral colours instead of bright ones, a still medium shot instead of moving the camera closer as the couple shares bigger sparks, and by scoring the scene with Trent Reznor’s eerie instrumentals instead of a Top 40 pop hit, Fincher breaks the conventions of the romantic comedy Amy’s story suggests she thinks she was living. He also tips us off that something’s amiss by showing Amy writing in her diary in a pink fluffy pen, something you might expect from her-six-year-old self but not the sophisticated, educated woman we meet in the film.

We never get inside Nick’s head to the same extent as Amy’s. We can see his sister Margo calling him on his bullshit or Amy telling him what she knows he’s thinking, but once we get past the turning point, where the key secrets get revealed, he’s opaque. There are advantages to this: when we see Nick committing a violent act, we have to constantly question if this is fact, fiction, or some kind of dream. Because everything we’ve seen so far suggests that any of these is possible. But it’s Fincher that’s playing with our heads, fueling our suspicions, not Nick.

Instead, we get a read on Nick based on how the other characters approach him and react to him. Since Nick doesn’t have the insight to really understand his relationships with them, Fincher actually ends up giving us a more objective perspective on Nick. The way Margo looks at her brother speaks volumes: she loves him, but she can also see right through his bullshit. Detective Boney’s straight posture and direct manner tell us she’s a no-nonsense kind of woman; our opinion of her is not filtered through Nick’s libido as it is in the book. And we need only look at Nick’s childish mistress to see immediately how pathetic and desperate he is for what Flynn calls a “Cool Girl”: a low maintenance woman who lets you project everything onto her. But since the crux of the book was about the stories that Nick and Amy tell themselves about themselves and their relationship, this issue of the performance of identity gets lost and muddled.

Ever since Flynn’s novel was released, people have been arguing over whether or not it’s a misogynistic text because neither Amy nor Nick are particularly likable. If you’re paying attention, it’s unquestionably a feminist text. This is largely because of how Amy and Nick relate to each other. We have to be convinced of just how excellent and amazing Amy is to accept, and to a degree, justify, her actions. Fincher’s camera loves Pike, and he makes sure that she’s constantly keeping us guessing. The film makes Amy more compelling, if also more purely crazy and psychopathic and less realistically flawed than the book does. We also have to be convinced of Nick’s mediocrity, which both do. Just as important, though, is Nick’s understanding of his own mediocrity and Amy’s superiority. In the book, he understands that Amy is the only person who can keep him from regressing into the misogynistic shit that is his default. Her methods may be questionable, but they’re effective. The film sidesteps this. We see Nick’s adoration for Amy, but we don’t understand the complexity of it: we get that he’s attracted to her, but we never see just how much he needs her.

The result is that neither character seems grounded in reality, which makes the film less of an observant satire and more just purely pulp. It’s hard to know who to blame here. Did Flynn’s script originally have a more convincing way of revealing this than by having Amy tell Nick that he needs her, which is so different from him coming to the realisation himself? Was it cut for time or flow, or did it never exist?

This missing piece makes the film a very different beast from the text, a less nuanced one that’s more open to interpretation as misogynistic. Amy’s crazy behaviour is less rooted in reality, less justified, and that makes her more of a caricature. Because Amy’s flashbacks are filtered through Fincher’s visuals, her behaviour in the past starts to make less and less sense because it’s not just her voice recalling it. Why would she deliberately put herself into a situation that causes her misery? Since Nick isn’t interacting with or responding to a realistic human, he, too becomes more of a caricature, and to some degree, a victim. In the book, Amy was a psychopath, but one with a valid point: she was acting out against the patriarchy. In the movie, she’s destructive, but she’s more purely a villain, albeit one we can’t help but root for.