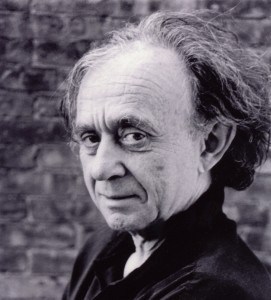

In this interview, Frederick Wiseman discusses capturing the paintings in National Gallery on film, his editing process, directing theatre, and how to familiarize yourself with his oeuvre. This is an excerpt from the ebook In Their Own Words: Documentary Masters Vol. 1, purchase a copy here. The book also features interviews with Wiseman on In Jackson Heights and Ex Libris.

At 84, American Master Frederick Wiseman has been making movies for 47 years, and he shows no signs of slowing down. He has directed 39 documentaries — among them, Titticut Follies, Welfare, and At Berkeley – and two fiction films, and he has held MacArthur and Guggenheim Fellowships. Each of his films takes a behind-the-scenes look at a different institution, whether a university, a hospital, the state legislature, or the Paris Ballet. There are no talking heads in Wiseman’s documentaries; instead, he takes a fly-on-the-wall approach, observing the goings on of the institution he’s filming.

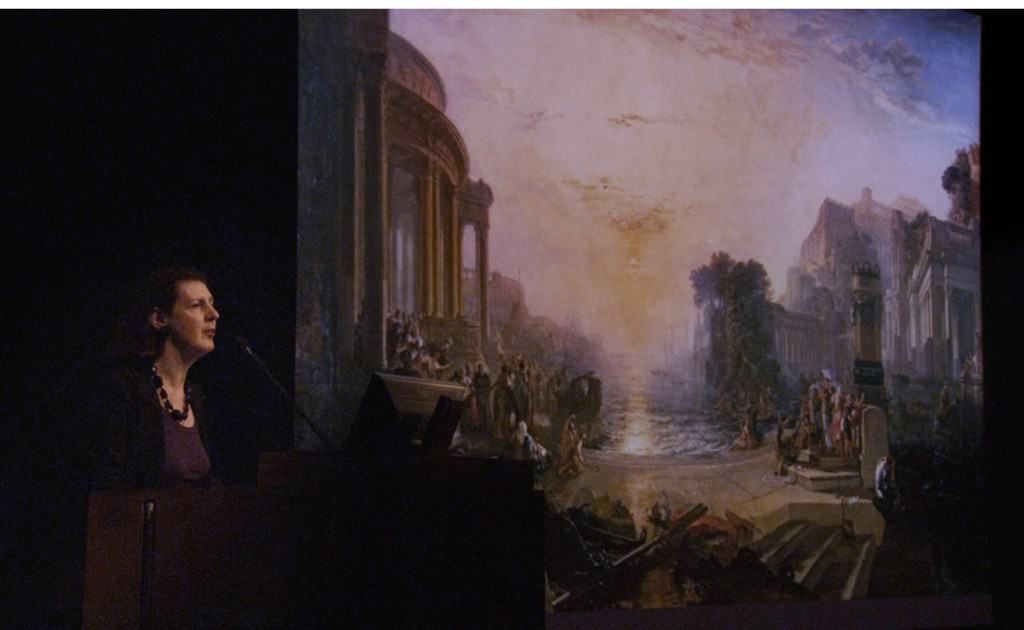

His latest film, National Gallery, which premiered in the Director’s Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival in May, takes a look at the inner-workings of London’s renowned art museum. We meet the staff of the National Gallery, the tour guides, the restoration department, the communications department, and the research department. We gaze at numerous paintings, often illuminated by a tour guide’s lecture, and we see the special exhibitions change throughout the year: we start with a Leonardo da Vinci showcase, then a J.M.W. Turner and Monet exhibit, and finally a Titian exhibit.

The film is a fascinating look at one of the greatest art museums in the world, its role in the community, and how the paintings it houses continue to speak to us. During his visit to San Francisco, I sat down with Wiseman to discuss the film, how he shot the paintings, his editing process, and how being a documentarian makes him uniquely well-equipped to direct theatre.

Seventh Row (7R): You said, in the press notes, that you first starting thinking about making a film about a museum 30 years ago.

Frederick Wiseman: I had tried a museum in New York, and they wanted to get paid. I neither wanted to pay them, nor, even if I had the money, would I. And then the National Gallery came up by chance. I was at a ski resort and I met someone who worked at the National Gallery, and she asked me if I was interested in doing a movie about a museum, and I said, “yes.” She arranged for me to meet Nick Penny, who’s the director of the National Gallery, and he said “yes.”

On capturing the paintings in National Gallery

7R: I would imagine there’s a certain kind of technical challenge with trying to capture all the paintings at the National Gallery with as much fidelity as possible.

Frederick Wiseman: There were several problems. I wanted to be sure that the colour was at least an accurate representation of the original colour. That in itself is a very complicated question, because the colour is dependent on the time of day and the nature of the light. If there’s sky light, the colour is going to be one thing; if it’s electricity, it’s another. If it’s dusk, it’s going to be one thing; if it’s noon, it’s another.

Provided courtesy of Zipporah Films

I decided very early on that the way I wanted to shoot the paintings — when it was possible, and it wasn’t always possible — was inside the frame, because I thought the painting became much more alive when you didn’t see it as an object on a wall, with a plaque next to it, giving the name and dates of the painter.

For those paintings which are story paintings — as many of them are up to the beginning of the 19th century — I found that you could shoot them serially. You could do closeups of different parts of the painting, and present the closeups serially, which is different from the way the eye takes in a painting. It begins to resemble more a movie, or a novel, because the form of storytelling is serial, as opposed to instantaneous.

7R: There aren’t shots where you’re moving the camera as if it’s someone’s eye scanning the painting.

Frederick Wiseman: There are no panning shots, because I don’t like panning shots. But there are lots of, in some of the story paintings, like Holbein’s The Ambassadors, you see closeups of different parts of the paintings. I cut those close-ups to be linked to what the guide was saying about the painting. But at the same time, you’re both seeing the whole painting, but you’re seeing the painting in serial form, which is different from the way you look at a painting in a gallery. But [it’s] similar to the way you look at a sequence in a movie, or read a chapter of a novel, or the whole novel.

To read the rest of the interview, purchase a copy of In Their Own Words: Documentary Masters Vol. 1 here. The book also features interviews with Wiseman on his films In Jackson Heights and Ex Libris, plus a comparison between Wiseman’s documentary filmmaking philosophy and Gianfranco Rosi’s.

[wcm_restrict]

7R: Did the precision of the colour affect what cameras you used?

Frederick Wiseman: No, it was the same camera all the way through, but in the colour grading, you have an opportunity to make corrections — you have to have good material to begin with. During the colour grading, we had books with us, published by the National Gallery, with pictures of the paintings. If I wanted to check on the red in a painting, I had the book as a reference. [We were operating under] the assumption that if the National Gallery approved and published the picture of the painting in the book, that they thought it was an accurate representation of the painting.

Also, the colour grader went to visit the National Gallery before we did the grading — he was there just one day, but I gave him a list of all the paintings [in the movie] — so that he had a chance to look at what they were like. But basically, it was done in the original shooting, and could be fixed up a little bit in the colour grading.

7R: That brings up an interesting question of how do you represent different art forms on film. Like, if you’re filming dance or theatre, as you’ve done before in Ballet, La Danse and La Comédie Française, it’s not just a horizontal art form, but a vertical one. How do you translate that into film, which is a horizontal art form?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, you have to find a way that suits you. Before I did Ballet and La Danse, I’d seen a lot of dance films, which I didn’t like, because the filmmaker put the dance at the service of the filmmaking. So there’d be a lot of elbows, a lot of tight shots. But dance, unless you see the body, the whole body, not just of the individual dancer, but when they’re partnered or when the corps is dancing, the dancers. Otherwise, you’re not seeing the dance; you’re not seeing the choreography.

So I decided early on that when that was possible, I wasn’t going to do shots of elbows and hands and toes. There’s a little of that, but you’re going to see the compositions that the choreographer had in mind. That’s what I mean about the film at the service of the dance and not the other way around.

The same is true of the paintings. At least, as one of the shots, you see the whole painting. But I didn’t resist the opportunity to break the painting down into parts, because you could really have a closer look at the painting that way. The lens can do what the eye can’t.

On editing

7R: What is your whole editing process? What do you do from start to finish?

Frederick Wiseman: For National Gallery, it took about 13 months. I start off by looking at all the rushes, making notes about them — that may have taken, in the case of National Gallery, a couple of months. I then edit the sequences that I think I might use in the film. When I’ve edited all of those, after that first go round, I put aside about 50% of the material. Then, I edit the sequences that I think might be in the final film. It’s only when I’ve edited all of those so-called “candidate” sequences, in close to final form, that I begin to work on the structure.

At that point, I can work out the first assembly rather quickly, because all the sequences I think I might use are in decent shape. That first assembly comes out to be usually 30 or 40 minutes longer than the final film. After that, I work on the internal rhythm within the sequences and the external rhythm in the way the sequences are linked. I change things around quite a bit. Then, when I think the film is finished, I go back and look at all the — in the case of National Gallery, all 170 hours — footage all over again to make sure that there’s nothing that I rejected that has become important as a result of the choices that I’ve made.

7R: When you first compile the individual segments or parts in the editing room, do you find that a certain kind of rhythm starts to emerge with each of those?

Frederick Wiseman: No, not in general, but when I’m editing individual sequences, I’m trying to find the rhythm that’s appropriate to that sequence. For example, in [At] Berkeley, those meetings with the Chancellor’s cabinet would go on for an hour-and-a-half, but any one of them in the movie is probably [only] nine or ten minutes.

So it’s a question of deciding what I think is important in that meeting, how I can compress it, or condense it, or summarize it, in a way that doesn’t distort the meaning, and simultaneously works in film terms — whatever that means. I don’t get involved in the relationship between that sequence and the other sequences until much later, when I’m trying to figure out the structure. And the structure is really toward the end.

7R: How do you approach the internal rhythms of the individual scenes, and the rhythm of the entire movie?

Frederick Wiseman: The rhythm is different for every film, and the rhtyhm is a response to the material I have. To take the obvious contrast, the rhythm in La Danse is very different from the rhythm in Welfare, because La Danse is music and bodily movement, which establishes a [certain] rhythm. A movie like Welfare is much more dependent on the rhythm of pictures — I’m not saying the rhythm of pictures isn’t important in La Danse — and the nature of the conversations. Word is more important in Welfare, State Legislature, and At Berkeley than it is in Primate or Zoo.

The rhythm of each of the films is a response to the nature of the institution, as it’s been recorded on film. If there’s a lot of marching and singing, it’s one thing. If there’s a lot of talking in an office, or around a table, it’s something else. But the nature of what constitutes rhythm is different, too, because if you’re editing a meeting, you can make it visually more interesting by using cutaways of the participants who aren’t talking, that are responding — through their gestures or expressions — to the content of the discussion.

7R: How do you figure out what order you’re going to put things in?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, I have to have a reason. I start off with no point of view toward the material, no thesis. The film emergences as a consequence of the experience of being at the place, and thinking more specifically about it, in the course of the editing, in making the choices.

I like to keep an open mind — or at least I think I have an open mind — during the shooting and during the editing, so the final film is a response to the experience, to what I’ve learned as a consequence of the experience, rather than the imposition of pre-conceived views.

There are always new ideas, or ideas new to me are being stimulated, by the editing of individual sequences, and then making some judgement about the consequences of putting them in a particular order, and trying out different orders. One of the ways I know the film is finished is that I have to be able to explain it, with words, why I’ve done what I’ve done, why each cut is there, what its relationship is to what is before and after, etc.

On directing theatre

7R: You also direct theatre in addition to making films. There are a lot of fiction filmmakers also directing theatre, but not as many documentary filmmakers doing so. How did you get into that?

Frederick Wiseman: I’ve always been interested in the theatre, and making documentaries is fantastically good experience for directing actors, because you’ve seen people in so many different kinds of situations. You have this great reservoir of experience to draw on when you’re trying to figure out what to do with the actors. Part of the interest, for me, in making documentaries, is I get exposed to such a wide array of human experience, and that’s useful here. It helps avoid cliches when you’re dealing with actors, because you have a wide range of associations to call on.

7R: For understanding human behaviour?

FW: Yeah. The movies are about people from all different social classes, races, educational experiences, and about violence, tenderness, kindness — they’re all the emotions you need to deal with in the theatre. It’s great to be able to imagine responses and say, “Oh yeah, remember that time? What she did with her hands that day? Maybe that’s something I can use here?”

7R: Do you find that directing a documentary film is in any way similar to directing for the theatre?

FW: It’s different because [in documentary filmmaking] you’re not telling people what to do, you’re figuring out what to shoot and how to shoot it. The similarity becomes more in the editing. You have to analyse a play, to figure out what you want to tell the actors to do. In a documentary, you have to analyse the sequences, and figure out what’s going on, in order to know 1) whether you want to use it and 2) how you want to use it. So that’s very similar.

When I do a play, I have to analyse the text, I have to say to myself, “Why is this person saying that to that person? What did the writer have in mind? Does it work? Is there some metaphorical significance to it? How do you translate it into gesture?” I have to do the same thing in documentary. I have to say, “Why did somebody pause at this moment? Why did they ask for a cigarette at that moment? Is there any significance to the clothes they’re wearing?”

In order to make people initially understand the sequence, and make the choice as to both how and why I want to use it, the analysis is the same. The fun of both doing theatre and movies is that you’re putting yourself in a position where you have to think about behaviour, and a wide variety of acts that we, as people, do.

For the neophyte to the Wiseman oeuvre

7R: For somebody not familiar work, which of your many movies would you recommend starting with?

Frederick Wiseman: Welfare, maybe. La Danse. National Gallery. I tend to like the most recent ones because I remember them better: [At] Berkeley.

[/wcm_restrict]