In this interview, Yann Demange discusses his first feature, ’71, shooting on digital and 16 mm, working with the super talented Jack O’Connell, and more. This interview with Yann Demange was one of the first conducted on ’71.

Read our review of the film ’71 here.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

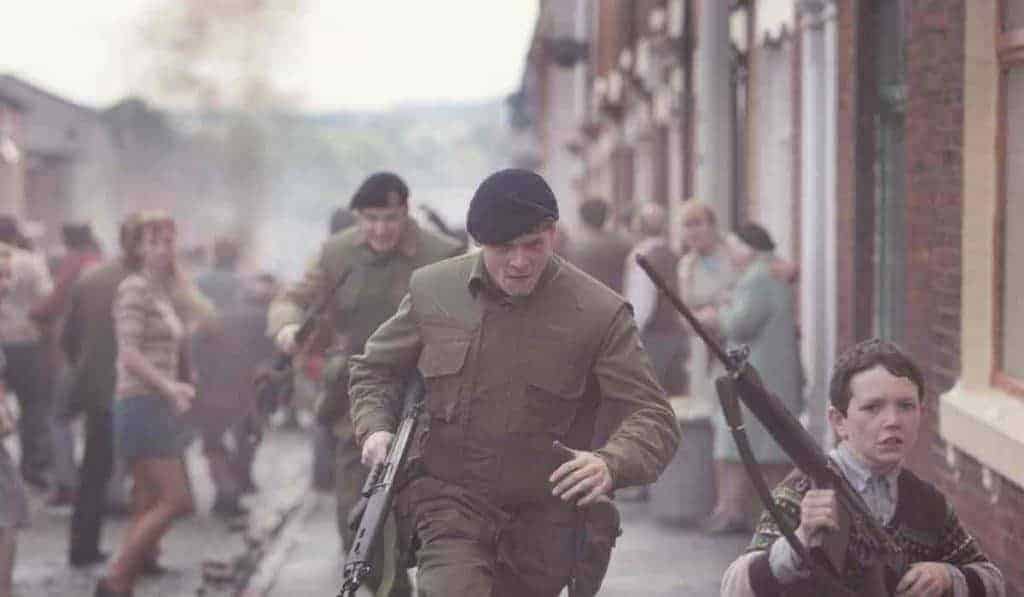

After a year-long tour on the festival circuit following its premiere at the 2014 Berlin Film Festival to rave reviews, the political thriller ’71, by British director Yann Demange, is finally opening in cinemas. Set in 1971, at the height of The Troubles, the film follows neophyte British soldier Gary Hook (Jack O’Connell in another star-making turn) on one fateful night in Belfast, when he finds himself injured and separated from his unit, deep in IRA territory. He spends the night struggling to survive, desperately trying to differentiate between friend and foe: the lines are constantly being blurred.

It’s a tense and thrilling film about an under-equipped soldier, thrust into a war he doesn’t fully understand, by a well-meaning commanding officer who doesn’t fully grasp the situation: mistakes get made, people get crossed, and as Gary starts to see the humanity in the other side and the cruelty in his own, he starts to lose the conviction to fight this fight.

Although this is Demange’s first feature, he’s already had a long and fruitful career in British television. Since the film is opening on the heels of Unbroken and Starred Up, it may seem like yet another film in which Jack O’Connell gets beaten up (can’t he just wear jeans and tell jokes, like Tom Hiddleston wants to?), but O’Connell was actually cast in ’71 first, which was shot just two weeks after Starred Up in spring 2013: they actually had to shoot the film backwards since dark hours were in increasingly short supply.

During the Sundance Film Festival, I sat down with Demange for an interview to discuss shooting digitally and on 16mm, creating the film’s tone and pace, collaborating with the writer and director of photography, and O’Connell’s remarkable performance.

Seventh Row (7R): Although the film ’71 is very much about The Troubles and steeped in the politics of that time, there are no title cards to explain the history or background. You’re thrown right in.

Yann Demange: I made a conscious decision not to try to explain to everybody, so you experience it with him [Gary], really. There isn’t that kind of political overview. Even in the U.K., nobody really knows the history, because they don’t teach it in schools. I knew, because I grew up with Thatcher talking on the news. But my niece and nephew — she’s 23, he’s 21— have just gone through the London schooling system: they don’t have a clue.

They still don’t teach it: 80% of the people we’re going for, who are going to the cinema, would know nothing about The Troubles. Do you take time to explain an overview and take everyone to school? And then start the story? I decided not to in the end. It’s actually a virtue, because it makes you more committed to Jack’s experience.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘When I’m in the riot, I sort of smash you across the face. It’s frantic.’ – Yann Demange” quote=”When I’m in the riot, I sort of smash you across the face. It’s frantic.”]

7R: You chose to shoot parts of ’71 handheld and very shaky, which I so often hate, but I loved it here. Can you talk a bit more about that decision?

Yann Demange: It’s because it’s not all handheld. I think people think of it as a handheld film because of the riot, but actually, the whole front of the film, I’m on the sticks or Steadcam: quite still, quite steady. I mix up all the styles. When I’m in the riot, I sort of smash you across the face. Everyone remembers the riot, the chase. It’s frantic.

I mix a lot of styles. When the film goes nocturnal, as the sun goes down, I wanted to transcend realism a bit. I tried to make the lighting get a little mythic. It takes a little bit more [of an] impressionistic quality, at times. I actually see it as quite a lot of SteadiCam work, a lot of dolly work, a lot of tracking, still shots. But we mix it up. There are definitely lots of handheld moments, too.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘When the film goes nocturnal, I wanted to transcend realism. It gets an impressionistic quality.'” quote=”When the film goes nocturnal, I wanted to transcend realism. It gets an impressionistic quality.”]

It’s a film where somebody’s constantly moving. He’s chased. Even when it slows down, when it’s on the estate, it’s cat and mouse. It’s still movement. There’s quite a lot of Steadicam. I don’t like it when the camera becomes too distracting.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘We talked about why and how the camera moves, knowing the camera would almost constantly move.'” quote=”We talked about why and how the camera moves, knowing the camera would almost constantly move.”]

Style and content have to go hand in hand. Me, the cameraman, and the DoP, we’ve been working together 10 years now. We talked a lot about why and how the camera moves, knowing that the camera would almost constantly move. The camera behaves differently with the MRF, for the soldier guys that are chasing him, and we use certain lenses. We mix it up a bit.

7R: What was the thought process behind changing the look of the film ’71 depending on where we are in the film?

Yann Demange: Every storyline had its tone. I didn’t want to do something that was overstated, like different colours, but it has actually its own little language, its own set of rules. There a logic to how we’re shooting each character’s storyline.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘There a logic to how we’re shooting each character’s storyline.’ – Yann Demange” quote=”There a logic to how we’re shooting each character’s storyline.”]

We talked a lot about how the colour palette would change, as the story progressed, and how the camera movements would change, and almost counterintuitively get slower and slower in the film.

After you have such a visceral, fast chase, the convention is often, in what could be perceived as an action film, for the set pieces and the action to get bigger and stronger at the end. But we wanted to counter-intuitively do it the other way.

I get action fatigue when films do it like that. I like sparseness. Anything can become monotonous if it lasts too long so attempting to try and keep it fast and fast and frantic and loud, I think would have been a fallacy, it would have become monotonous.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘To keep the tension, we slow it right down, and we change the colours subtly.’ – Yann Demange” quote=”To keep the tension, we slow it right down, and we change the colours subtly.”]

To keep the tension, we slow it right down, and we change the colours subtly. We change the whole tempo and mood of the film so it almost becomes a different genre. That was the logic and the sort of things we talked about.

We created a tone book, a tone document, with music references, film clips, photographs, colour palette references, paintings. All the heads of departments were invited to contribute to the tone book, so we all feel invested in creating the world together. It’s like a blueprint. We all know that we’re trying to make the same film.

7R: The light at night gets impressionistic. How did you create that?

Yann Demange: We mixed formats. We shot 16 mm film for the day scenes, because the textures, the skin tones, and the grain felt right for the period. We liked the way it rendered the uniforms. During the day, it’s very much reds and greens: red bricks, green uniforms. We tried lots of different formats. We did screen tests with full costumes on locations. And 16mm just felt like the right format. It’s a lovely camera to handhold. It felt right for the riot. Almost all the news footage of the time was shot in 16mm. It felt like the format of the time, of the era, but they shot in black and white.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘We shot 16mm for the day scenes. The textures, skin tones, and grain felt right for the period.'” quote=”We shot 16 mm film for the day scenes, because the textures, the skin tones, and the grain felt right for the period.”]

At night, we didn’t want to use any fill lighting. We just wanted to use a mercury light. We wanted to capture the sense of a city that’s pitch black and just have the occasional mercury, sodium lightbulbs, streetlights, just sparse street lighting. We wanted to capture that and not create a sort of moonlight effect that some films do. That meant that film — the stocks aren’t fast enough. We decided to go with the Alexa at night, shoot digital at night, so it could really work in low light conditions.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘The 16mm, in the day. gave us better continuity of light…when the weather keeps changing.'” quote=”The 16mm, in the day. gave us better continuity of light…when the weather keeps changing.”]

The 16mm, in the day. gave us better continuity of light. When we were shooting the riot scene, for instance, over three or four different days, and the sun kept coming in and out, 16mm is much kinder with the highlights. Creating a kind of continuity over day scenes. when the weather keeps changing, and more importantly, I preferred how it was on skin tones.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘At night, we used period lightbulbs, the sodium and mercury lightbulbs they had at the time.'” quote=”At night, we used period lightbulbs, the sodium and mercury lightbulbs that they had at the time. “]

At night, we were using period lightbulbs, the sodium and mercury lightbulbs that they had at the time. We had a few period light fittings. We’d put up our own street lights with our own bulbs. They just looked like practical lights, but then we wouldn’t add any fill. Occasionally, we’d have to add little light so you can see the star’s face, but very minimal.

7R: Jack O’Connell gives an amazing, often silent, performance in the film.

Yann Demange: Jack was the only person that could do this role, I felt. He’s just got this old school masculinity. He’s like an old soul. There’s something soulful about him, and you know he’s felt pain. He’s in that perfect period of his life, on the cusp of manhood. He understands this character. He grew up wanting to be a soldier or a football player. He’s not affected or pretending. He understands this kid.

[clickToTweet tweet=”Yann Demange on Jack O’Connell: ‘There’s something soulful about him. You know he’s felt pain.'” quote=”Yann Demange on Jack O’Connell: ‘There’s something soulful about him. You know he’s felt pain.'”]

He has this wonderful ability to communicate thoughts, to give you a sense of what he’s thinking and feeling without having to rely on dialogue. That’s very rare for someone his age. He can really hold a silent moment and give you the space to project onto him. It’s very sophisticated, that performance, and brave. He’s not vain. He’s not afraid to show his vulnerability and go there. He’s quite committed. I think he’s a star. I hope he has a big future ahead of him.

[clickToTweet tweet=”Jack O’Connell ‘can really hold a silent moment and give you the space to project onto him.'” quote=”Jack O’Connell can really hold a silent moment and give you the space to project onto him.”]

7R: How did you collaborate with the writer and your director of photography (DoP), especially when it came to choreographing the cat-and-mouse chase at the end of the film?

Yann Demange: A script isn’t a film. It’s not a blueprint that you go off and cover. A film is an ever-evolving thing. And the writer, Greg [Gregory Burke], is very collaborative. Even when I was shooting, he would be rewriting scenes, because I might have changed something when I shot a scene, and it might have a knock on effect. The whole film was forever evolving, so re-writing.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘We went on location — the DoP, the writer, and me — and choreographed where everybody would be.'” quote=”We went on location — the DoP, the writer, and me — and choreographed where everybody would be.”]

When it came to the cat-and-mouse sequence on the estate, on the housing block, we went on location together, the DoP, the writer, and myself, and choreographed where everybody would be. We wanted to have a geographical sense, for people to have a sense of reality, of what was going on, for it to play out, but also to create tension. But we had to play it out, literally act it out. How he’d [Gary] end up starting, where he would be coming from, where he’d be going down the stairs. It was all too complicated to be doing in our bedrooms, or in our office around our table. We had to go walk the location, and that would inform the writing.

Read more: In addition to our interview with Yann Demange, read our review of the film: In Yann Demange’s ’71, a British soldier is lost in IRA territory >>

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch great films like Yann Demange’s ’71 at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.

Click here to subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter.