Two Sundance hits explore how empowered women function within a patriarchal society. They pose the question, can you defeat the patriarchy simply by exercising agency?

Sonita, the subject of Rokhsareh Ghaeemmaghami’s eponymous documentary Sonita, is an Afghani refugee in Iran who dreams of being a rapper, performing indictments of the patriarchy to packed houses. She’s taking back the voice that her culture has denied her: in Iran, it’s illegal for women to sing. But Sonita’s family has other plans. Her brother needs money to purchase a wife, so the family angles to sell Sonita as a bride to the highest bidder. In her mother’s words, “This will solve everyone’s problems.” If Sonita refuses, she’ll be beaten.

Layla, the young Bedouin woman at the centre of Elite Zexer’s poignant drama Sand Storm, dreams of finishing her studies and marrying for love. As a university student, she’s fallen in love with a Bedouin boy outside of her tribe. Although marrying outside of her tribe is unthinkable — she’s seeing the boy on the sly — she’s optimistic that her progressive father might consent to the match. But when Layla’s conservative mother, Jalil, discovers the relationship, her mother instructs her to put an end to it. At first, this seems like Jalil’s attachment to tradition. Eventually, we realise that Jalil is protecting Layla from her father — who will always bow to patriarchy in the end.

Both films explore how empowered women function within a patriarchal society. They pose the question, can you defeat the patriarchy simply by exercising agency? Sonita’s dream to escape opprssion and openly defy the patriarchy is a narrative that we conventionally think of as empowering. Layla’s journey, on the other hand, could be easily read as submissive. But Zexer is very careful to show Layla consciously making choices at every step, even saying aloud, “There’s always a choice.” Both filmmakers are less interested in the heroines’ eventual choices than in their acts of agency.

Ghaeemmaghami and Zexer each open by presenting a strong-willed young woman, only later revealing the restrictive culture she lives in. We first meet Sonita as she recounts her dream to be a rapper, but later, we discover it’s not even legal — and as an independent immigrant, neither is she. Ghaeemmaghami’s camera follows Sonita from behind as she walks the streets of Tehran alone, the image of an independent woman. Similarly, Zexer opens by introducing Layla’s loving relationship with her father as they discuss her university studies and he teaches her to drive. But then we learn that he’s just taken a second wife even though he deeply loves Layla’s mother and didn’t want to. But it is expected of Bedouin men.

Sonita and Sand Storm don’t present patriarchy as a struggle between genders, but between generations of women: in both of these films, the enforcer of patriarchal values is a mother. We never even meet Sonita’s father. Instead, it’s her mother who insists she must marry and comes to make it happen. When Sonita tries to negotiate a better deal, it’s with her mother. Sonita’s mother has been co-opted by patriarchy, upholding tradition even though it has hurt her personally. Sonita’s school principal appeals to Sonita’s mother’s feelings about her own unwanted marriage, but she’s so hardened by it that she can’t see clearly.

Jalil, on the other hand, is sympathetic to her daughter’s wishes even though she knows they’re futile. Though she was certain her husband wouldn’t take another wife, she watched him do it anyway, because it was expected. Jalil knows that things will end badly for Layla if she insists on trying to win her father’s support. It’s just that she doesn’t know how to communicate this with kindness or tenderness. Instead, she tries to keep Layla in the domestic sphere, keeping her from school.

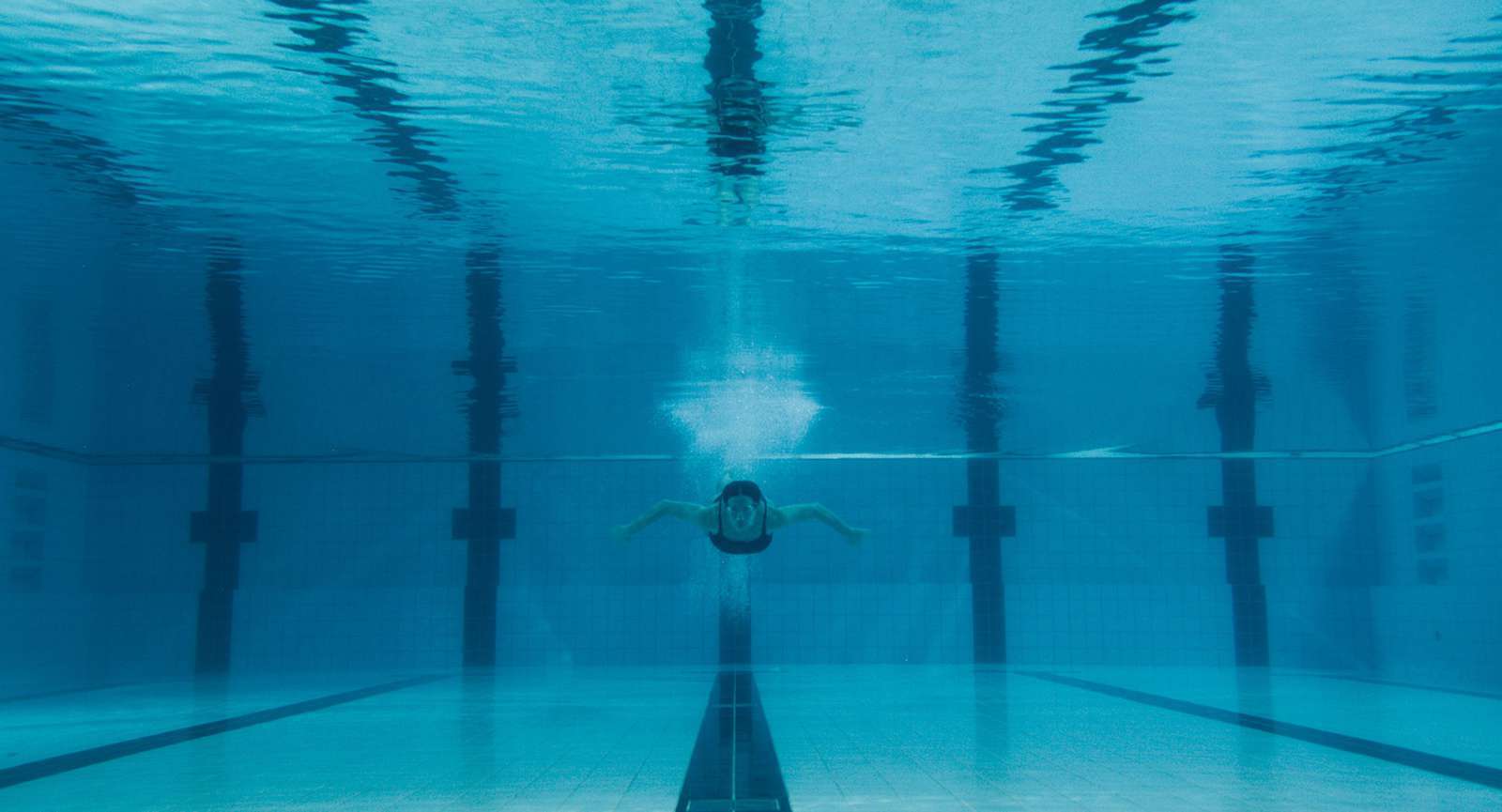

Yet, we can really feel the deep love and respect between Jalil and Layla, especially in Zexer’s two-shots. Jalil makes sacrifices to fight for Layla, and by the end, Layla has to choose between doing what’s loving for her mother and leaving everything she knows, including her siblings. Zexer gives Layla time to think over her decision, forcing her to move through symbolic spaces — like a long tunnel en route to her lover — where she must consciously decide where to go. Running away isn’t simple.

Much less goes unsaid in Sonita’s world. Sonita finds her empowerment by using her words. In an early scene, at school, she learns that a friend’s family intends to sell her as a bride. On the spot, Sonita comes up with a rap perfectly articulating what her friend wishes she could say to her family. To deal with her family, she learns to speak their language. The only thing they understand is money, so she conspires to use this to her advantage.

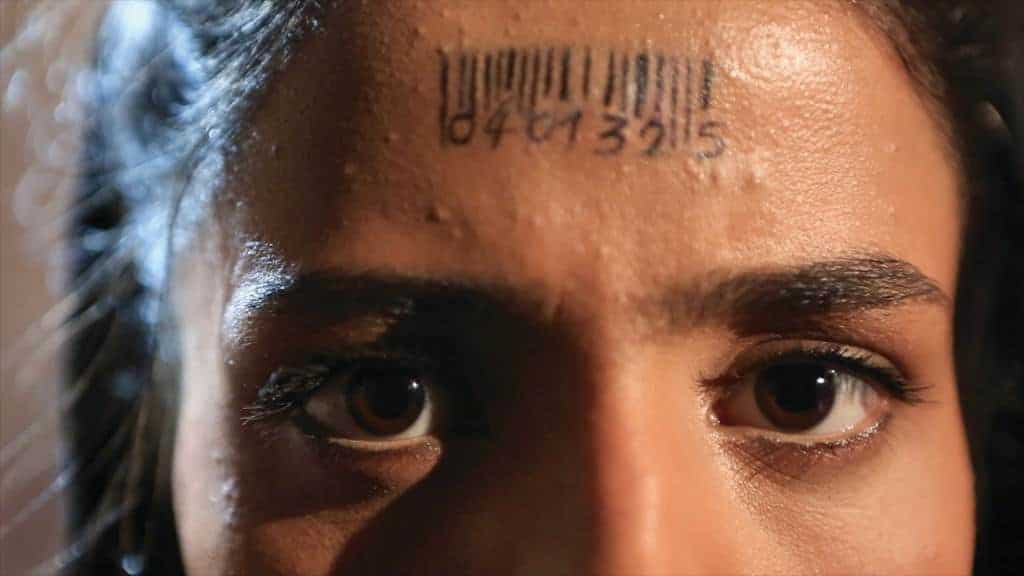

The music video Sonita shoots about the practice of bride-selling is a highlight of the film. She’s dressed in white with a veil against a black background, with black eyes painted onto her face and a barcode drawn on her forehead. Sonita won’t be silenced: she’ll record her voice and tell the world. Though the video doesn’t change her family’s mind, it’s a small victory that her younger siblings can recite the lyrics in rhythm.

If Sonita falters, it is that Ghaeemmaghami begins to insert herself more and more into the narrative, affecting Sonita’s trajectory. Ghaeemaghan’s first on-camera appearance is reluctant; it is Sonita who insists on flipping the camera on her. When Sonita seeks Ghaeemmaghami’s help with her financial problem, Ghaeemmaghami at first refuses, saying she’s there only to document and not to interfere. Yet Ghaeemmaghami never explains the root of this philosophy or what it means for this documentary when she begins to bend her own rules. I think she’s trying to show how her own struggle mirrors Sonita’s: staying silent, whatever convention may dictate, is impossible. But this a minor quibble. Sonita is a force to be reckoned with, and the film is one to be seen.

Although Layla’s and Sonita’s options are dictated by the needs of men — Layla’s dad, Sonita’s brother — the relationship that defines the conflict is between the heroines and their moms. Even the well-intentioned Jalil finds herself reinforcing the very patriarchy that is causing her current anguish. Layla may start out closely allied with her father, even against her mother, but by the end, Layla knows that only Jalil can truly understand how she feels. In contrast, part of what drives Sonita to leave is the realisation that her relationship with her mother and family is hopeless: they’ll never care about what’s best for her. At least, with her music, she can give her younger siblings a voice, so they, too, can choose their fates with eyes open.

Read our interview with Sand Storm writer-director Elite Zexer here.

More Sundance interviews with female directors:

Anna Rose Holmer on The Fits

Maggie Greenwald on Sophie and the Rising Sun

Rebecca Daly on Mammal