Legendary documentarians Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker reflect on the making of their film Unlocking The Cage about the fight for human-like rights for intelligent non-human animals. This is an excerpt from the ebook In Their Own Words: Documentary Masters Vol. 1. To read the full interview, purchase a copy of the ebook here.

Do intelligent non-humans like chimpanzees, elephants, and dolphins deserve human-like rights? According to Steven Wise, the animal rights lawyer at the centre of Chris Hegedus’ and D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary Unlocking the Cage, it’s overdue. Hegedus and Pennebaker followed Wise’s efforts to mount a legal argument on behalf of these animals, who have virtually no rights — they’re treated no differently animals that we eat. Hegedus and Pennebaker show a great deal of empathy in how they shoot these impressive species, showing us both closeups of their emoting faces and wide shots of their complex social interactions. In so doing, the filmmakers expose the problem that the law has yet to catch up to science. Yet Unlocking the Cage never loses sight of its main character, Wise, and what has driven him to this fight.

Apes, especially chimpanzees, have extraordinary intelligence. In the 1960s and 1970s, some of them were taught sign language and were able to communicate with the scientists studying them. Until now, documentaries in popular culture tended to explore the limitations of ape intelligence — how we can think they’re just like humans, but where this idea breaks down. Project Nim tracked the famous eponymous experiment in which the chimpanzee Nim actually lived with the scientists working with him, until he matured and became dangerous. Nicholas Philibert’s Nénette followed the forty-year-old titular orangutan in the Jardin des Plantes, and asked us to question whether we saw empathy and human qualities in her face because we were projecting or because they were really there.

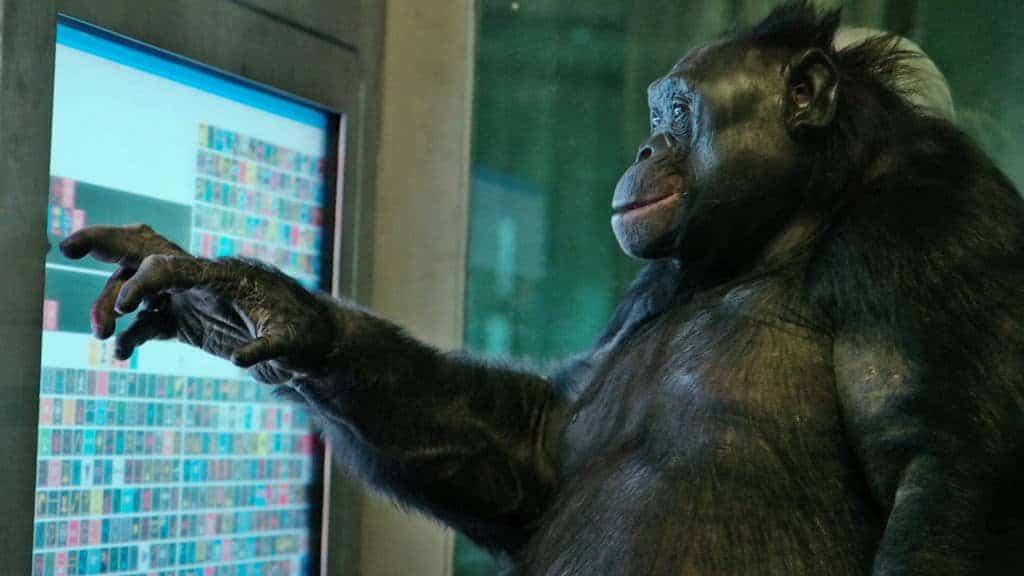

Unlocking the Cage mixes historical footage from the ‘60s and ‘70s with original present-day footage taken by Chris Hegedus of chimpanzee research. In one scene, we watch a chimpanzee play a memory game with impressive speed. In another, a chimpanzee watching a movie turns away at the sad part, and signs his feelings of sadness. Hegedus was moved by the deep emotions that the chimpanzees can express. She recalled, “It’s really interesting to see another being express things to you that are abstract like colours or feelings, not just naming objects. It was really extraordinary.”

When Hegedus first visited the Fauna Chimpanzee Sanctuary, she had the opportunity to meet to chimpanzees Tatu and Loulis. Tatu and Loulis — who was “the first chimpanzee to be taught sign language by another chimpanzee” — had just been moved to Fauna from their previous home and were having trouble adjusting. “They had just been moved there out of quarantine,” recalled Hegedus. “They were a little angry, at first, in the way that if you left your child at camp and didn’t come back for an extremely long time… I would have liked to have more signing with Loulis, but he became very shy when he moved up to the sanctuary.” Hegedus added, “Most of them had been torn from their mothers in Africa and brought to this country. The way that they created that space for them in this country was really novel: [at the sanctuary], the chimpanzees] could make communities together with other random chimpanzees that had this horrible life.”

The Fauna Sanctuary also houses chimpanzees that were used in early AIDS research — all of whom Gloria rescued. “Chimpanzees, even though they get AIDS and had been injected with it, they don’t have any reaction to it,” elaborated Hegedus. “So they’re not useful candidates. But they were all injected. Gloria rescued them and moved them all to her sanctuary. The neighbours were very scared because they thought she was bringing these AIDS animals up to us, and we could get AIDS. She thought she could get AIDS from them. But it turned out, they didn’t spread AIDS to each other or to humans. You have so much respect for people who do that kind of work because they give their whole life to it.”

To read the rest of the interview with Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker on Unlocking the Cage, purchase a copy of the ebook In Their Own Words: Documentary Masters Vol. 1 here.

[wcm_restrict]

Although most of us recall that a lot of chimpanzees were brought into the country for the space program, what happened to them afterward is a story much less well known. “A three-year-old chimp could fly a rocket,” explained Pennebaker. “People had to think these were pretty smart creatures. When they decided the rockets were safe, they dumped the chimps on the medical world.” The same was true for chimpanzees from the entertainment industry, like those from 2001: A Space Odyssey and other movies: they had to be rescued, and many are now housed at the Center for Great Apes. “They grow to be 60–65 years old. Once you have one, you have to keep them in a cage his whole life. So you’re sort of imprisoning a smart being. That was really what Steve’s motive was. That didn’t seem fair. But the only way you could undo it was legally. You had to get the law on your side. You couldn’t just go and appeal to them out of fairness, because they were out to make money. Fairness was not a consideration.”

“Our films are kind of like detective stories,” said Hegedus. “We’re following real life, and we never know what’s going to happen. One part of it is the exploration of the filming in following the story, and the other is taking it all back and figuring out the puzzle of what story you’re going to tell. It’s usually predicated by real events. We’re following a character, and whatever he does, we do. But that’s hard, because it was a long four-year process, and trying to figure out how to juggle the drama of him trying to find his chimpanzee plaintiffs and some of them dying, and trying to explain exactly what habeas corpus is and what these decisions were on what ended up being three different cases with very different roots to them. A lot of it is trying to figure out what information to put and where so that it’s understandable to a general audience.”

Pennebaker added, “When you’re dealing with the chimpanzees, over a period of time, you realize that you’re not just making a film about a chimpanzee getting freed. You’re making a film about all chimpanzees, and in a sense, you’re making a film about Steve. So you begin to go into Steve’s life, You want to see what kind of person is caught up in this impassioned thing to try to save chimpanzees. It gets wider as you go.”

“The thing that film does is it drops you into a world,” said Hegedus. “If you try to describe there was this chimpanzee that used this computer number board, and he did those numbers, you could tell somebody about it. But just to see the chimpanzee do that is just astounding, because we couldn’t do it that fast. It tells you something in film, in real life, that you can’t get otherwise.” Pennebaker added, “You’re really there. If [Steve] were to write a book, or somebody were to print a story of an interview with him, how many people would come across it? But when you’re watching that film, you’re there, watching what’s going on in the world. That could go all over the world.”

Getting their audience to think differently about complex issues they may not be informed about is a major goal of the film. “After our premiere screening,” Hegedus recalled, “I had one friend that was really very skeptical about what we were doing though the years, which is easy, too. He watched the film and really felt that it changed how he thought about animals. He’d have to rethink that attitude that he had before. For me, if I can do that, that’s success. “

Unlocking the Cage will air on HBO in July 2016.

[/wcm_restrict]